For three years, which turned out to be my last three years in the plantations, I was manager of New Ambadi Estate in Kulashekharam, Kanya Kumari District. New Ambadi Estate was actually one of four responsibilities in the area, which the manager of the estate automatically inherited. There was New Ambadi Estate itself, then there was an out-division called Greenham, there was a centrifuge latex factory in Nagercoil, and there was the AMM Arunachalam Charitable Trust’s school in Thiruvattar. And there was a hospital also run by the Trust with a full time doctor and his wife who was also a doctor. All came under the authority of the Ambadi manager and for someone who wanted variety in his work, I couldn’t have asked for more.

Ambadi was in a peculiar state when I took over. Since its acquisition by our company in 1942, it was managed by a British planter called Watts Carter for perhaps 25 years. He was a remarkable man with an amazing talent for engineering. He created rainwater harvesting tanks, built roads, revetments, and planting terraces. He planted rubber and literally built a rubber estate that has few parallels in the country. He built a bungalow on the top of a barren hill and planted cashew and jack trees around it. The hill, rich in laterite, was capped by a flat rock on which the bungalow was located. This meant that the hill, in a thunderstorm, attracted lightening. We had lightning conductors on the roof but in a tropical storm sometimes we would have a flash of brilliant blue flash through the house. It did no harm. Just flashed from one end of the house to the other.

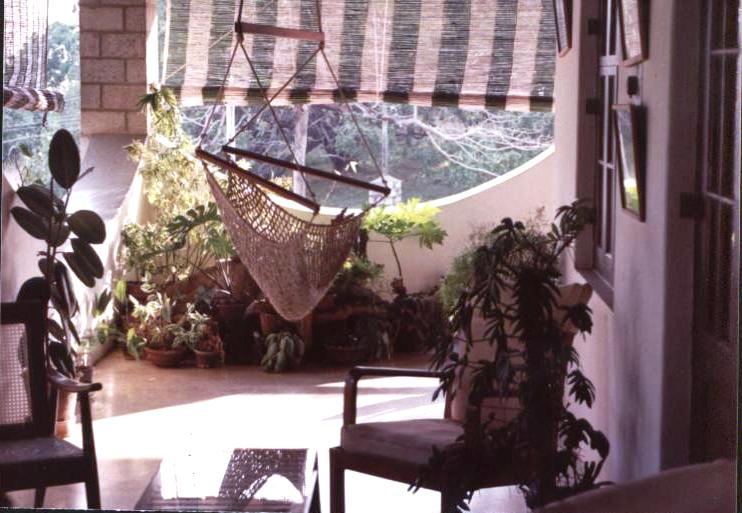

The bungalow itself was built on a ten-foot-high plinth surrounded by a wide veranda and a central roof peak going up to more than forty feet from ground level. It had a central hall with two bedrooms on either side with attached baths. All rooms opened out onto the veranda which surrounds the whole bungalow through tall, teak fold back doors with beautiful brass hinges. The rooms had no ceilings originally, though the walls between them were fourteen feet high. It is interesting to imagine the sharing of conversations between occupants of the different rooms.

Mercifully, one of the later managers, built ceilings, so by the time I became its occupant the bedrooms had become nice and cozy. However, the central hall retained its original beams and the high ceiling peaking inside to more than thirty feet from the floor. The roof consisted of the traditional Kerala roof-architecture of a grid of rafters and slats resting on the beams and covered by hard-baked earthen tiles which are known in South India as Mangalore tiles. Quite a sight to see if you were lying on one of the couches. And more than a job to clean and keep spider free.

Watts Carter was an excellent planter in every way. The estate itself was fairly small to begin with, but with Watts Carter and his acquisitive urge at its helm for more than twenty years, it grew in size. Lands were acquired and by the time I became its manager, it was nearly two-thousand acres in extent. This included two-hundred acres of coconut plantation and one of the finest coconut nurseries in South India. Particularly delightful were the Malaysian Semi-tall coconut trees. They had huge green fruit which you could sometimes pick from the ground and had water that was sweet enough to make you think it had been injected with sugar. Amazing thing, the coconut tree.

The plantation also had the traditional Java Giant trees, which are more than thirty feet tall with the fruit right at the top. The bane of all of these were huge bands of monkeys (Bonnet Macaques) which roamed at will all over the estate. They were organized in huge family groups led by the dominant males and like all groups led by males, had pitched battles with other groups. They did not seem to confirm to any fixed territories but would compete for the fruit in the orchard around the bungalow and most of all in the coconut plantation.

I once watched a battle from start to finish and it was eerie to say the least. While one group was feeding, another would creep up on it, with its members spread out singly or in twos and once they were within range they would attack screaming at the top of their lungs. Lots of noise and not much actual fighting or killing. I do remember seeing monkeys with some scars, but I never actually saw a dead monkey because of any battle. The objective was to scare the other group away from the food and then to eat as much as possible and cram the rest into the mouth and cheek pouches before the other troop could regroup and attack. It was kind of a game in a way with some seriousness. I do remember wondering on one occasion the difference between male led and female led animal groups. I may be wrong, but I don’t know of any female led animal groups that exhibit this dominant, aggressive behavior of hostility towards one and all. Female led groups like elephants for example, are famous for their inter-group cooperation. Maybe there is a lesson in leadership for humans in this as well. Anyway, that is another discussion.

To come back to our monkeys and coconuts on Ambadi, it is amazing how a fruit that you need a sharp machete to cut through the fiber, the monkey would simply bite through and then drink the water and scoop out the meat. All part of monkey heaven, but totally disastrous to the crop for anyone growing coconuts for any purpose other than to feed the local monkey population. To add to the travails, shooting a monkey is as close to suicide as one can get in South India where Hanuman is worshipped.

We used to have guards who would walk around with air rifles, which could inflict a sting but would not kill. Monkeys being clever as they are soon figured this out. To add to this, the guards were perhaps the worst shots in the history of shooting, so if the monkeys stayed in the top of the tall coconuts, they were safe from all harm. And that is what they did. Very frustrating if you were a guard. And also, if you were the manager who had to answer to the bosses. “Well, you see the monkeys got the crop”. That was not an acceptable answer.

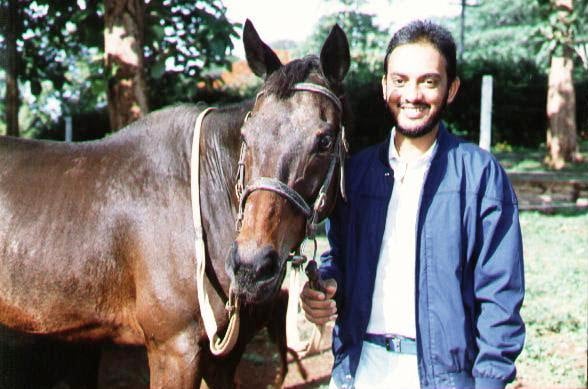

Tired of the monkeys ruining the crop, one day a guard shot at a monkey facing away from him and the monkey dropped out of the tree, dead before it hit the ground. His satisfaction was short-lived as he discovered that it was a female and had a very small infant which it was nursing. He brought the infant to me and I picked it up, screaming and all and handed it over to my syce (the man who looked after my horse – the groom) and so little Manju became a resident of my extended household. We built a little house for her on top of a 10-foot pole and she would sit on the platform of the house after a meal of bananas and milk and stroke her belly in sheer satisfaction. Manju, to her great disgust, was bathed with scented soap daily and then dried with a rough towel and powdered to boot. But in the hot climate of the rubber plantations, she found the aftermath distinctly delightful, especially when after the bath came her milk and bananas. She would eat her meal very daintily and then being as flexible as rubber, would wipe her little face on her distended round post banana belly.

All said and done, this change of lifestyle certainly did Manju a lot of good though I still regret the passing of her poor mother. Manju lived with us happily till I was in Ambadi, but then vanished one day. Maybe she fell in love with one of the handsome young lads in a troop and decided that a life of luxury was not as good as the company of the man you love. Who knows what goes on inside the head of a young female monkey brought up with a horse, two dogs, sundry pigeons, ducks, and a man who bathed her daily with scented soap?

The time between Watts Carter and myself was twenty-five years, in which Ambadi had only had two other managers. This period was also one of relative prosperity with rubber prices being good. As usually happens when product prices are good, they hide manufacturing inefficiencies. Discipline also tends to suffer as management is reluctant to enforce any rules that may tend to precipitate unrest and work stoppage. This is a lethal combination, especially in a highly unionized environment. Gradually, unions gain power at the expense of the management and overall productivity suffers and profits are shaved away. Eventually in Ambadi the situation got so bad and profits started bleeding so badly that one day the Managing Director Mr. M. A. Alagappan, called me and said, “I want you to go and take over as the Manager of Ambadi. Tell me, how long will you take to straighten things out?” I was in the Mango Range at that time, between jobs as it were and this was not just a good opportunity for me but the only one.

I knew a fair bit about the state of affairs Ambadi and knew that things would not be easy. But then it is only when you rise to challenges that you learn the new limits of your capability as well as get visibility in the corporate world. So, I asked him for permission to go to Ambadi for a month while the old manager was still there and observe the situation and then report back to him. He agreed and so one day, I landed in Trivandrum airport and the Ambadi car picked me up to take me to rubber land. This was my first time in the area. An area that was far from easy, full of dangers, and even some disappointments. An area which was to be my last stint in the industry. But nevertheless, a place that gave me the maximum satisfaction at overcoming challenges that were worthy of the effort. That was New Ambadi Estate.

It is strange in life that often the most difficult situations turn out to be the most rewarding if you make an effort to beat the difficulties. That was the case of Ambadi.

When I reached there, in a word this is what I found:

Staff in a state of despair. Totally demoralized and helpless, completely in awe of the union leaders. The union leaders themselves acting as if they owned the estate. Their arrogance was boundless and far more even than what I had encountered in Guyana where the union was the arm of the ruling party and its General Secretary was the Minister of Labor. For example, the union secretary of the CITU union would call the Ambadi Manager at 5 a.m. and say, “I have to talk to you about something important. So, come to the union office at 8 a.m. today.” The Ambadi Manager would go to the union office to listen to whatever it was that the union secretary wanted to demand. Another age-old accepted practice was that the union office bearers would come to the estate immediately after morning muster at around 6 a.m. and would hold a General Body meeting without any prior notice or permission.

This meeting usually lasted for more than two hours. After that the workers would go to their rubber tapping tasks. Since rubber yields best if it is tapped at sunrise, these meetings meant that the tapping was done two to three hours later on those days with a consequent loss of crop. This delay was also harmful for the workers who were paid an incentive on the amount of latex they tapped and so on the days they tapped less, they made less money, but nobody had the courage to question this practice.

There were many other such practices all of which served to underline the belief in the minds of the workers and staff that it was the union which really called the shots and management merely went along for the good of everyone. And that if anyone dared to rock this boat, it would mean big losses all around.

A third issue at stake and a source of much aggravation was the issue of CUT (Controlled Upward Tapping). This was a new method using a different kind of tapping knife that the management had been trying to introduce without success. Trees in their final phase of tapping, if tapped with this method, produced thirty percent higher crop is the first year because new panels are more productive. Since these panels are higher on the trunk of the tree, the tapper must use an upward overhead stroke which in more tiring and painful initially on the shoulder muscles. So, workers were very reluctant to use this method. I realized also that workers were not too convinced about the higher yield as they tended to be suspicious of all figures from the Rubber Board laboratories and elsewhere which were considered ‘management sources’.

Having been in Ambadi for a month and having taken stock of the situation I did three things. It is my belief that any problem can be solved provided we are willing to generate alternatives and try new things.

1. I asked for a meeting with my company and asked the Managing Director, Mr. M. A. Alagappan to give me a free hand to solve the issues in whatever way I saw fit. I promised to keep him in the picture at all times but asked for and was promised (and he kept this promise faithfully) his full support including permission to shut down operations if necessary. He was the person who sent me to this assignment and was more than willing to do what it took to see that I was successful.

2. I called a meeting of the Works Committee. This was a body of worker’s representatives who were technically the body that negotiated with the management on all issues to do with workers. In reality they were completely under the influence of the union leaders who were not on our rolls but who called the shots from the local town office in Kulasekharam. I decided that I needed to have a communication channel with the Works Committee independent of the Union as they were my workers so that I could directly speak to them and tell them my own position on various issues.

3. I called a meeting of the Staff (also unionized) with an idea to talk to them about what my plans for Ambadi were and how I intended to realize them. Mr. Murugan and Mr. Prem Kumar were their leaders. The Staff desperately needed encouragement and I needed their support if we were to be successful in our goals.

I was very fortunate in having with me five Assistant Managers: Arun Kumar Menon, Suresh Menon, Roshan Appaiah, Sunil Abraham, and Jayanand who were all fantastic young people and rose to the occasion and accepted the challenge that faced us. Without their full support and trust in me, nothing that we eventually achieved in Ambadi would have been possible. Suresh Menon had worked with me earlier in Lower Sheikalmudi Estate in the Anamallais. Roshan Appaiah was the son of my first Field Officer in Sheikalmudi Estate, Mr. K. A. Poovaiah, but this was the first time that I was meeting him. The others were new, as were all the Staff. So, I was in an alien area.

The first Staff meeting was truly memorable. I started the meeting with outlining what I thought Ambadi and its people could achieve. People looked at me with incredulous expressions and the only thing that kept them from walking out or telling me to my face that I was fantasizing is the inherent cultural respect for the authority that I represented. Once again, my fluency in Tamil was a huge asset as I could speak directly to everyone and could listen to them and understand them without the need for a translator. By this time I also had a fairly good hold of Malayalam, thanks to my time with Mallapuram workers in Murugalli, which was useful in Ambadi also.

I said to the Staff, “You have two choices. Believe me, do what I tell you to do whole heartedly and I will guarantee you results. Or join the ranks of those who want to fight me in this. There are enough of those and some more won’t make a difference to me. But what I can assure you is that I am here to stay. I am not going away. And I am going to achieve whatever I have said to you today. This I promise you.”

I stressed in my Staff meeting that if my Staff did what I asked them to do wholeheartedly, I would take responsibility for any failures. I learnt from experience that when you have a team that is skilled, but not motivated and afraid, then you as the leader need to be able to take the responsibility for failure off their shoulders provided they follow orders. This creates a cushion of confidence which then gets reinforced when they see success and they start to own responsibility in due course. But in the beginning if they are too scared of trying the new methods that you are advocating and you make no effort to deal with these fears, then they freeze and will either not act at all or if you are forceful they will work without enthusiasm and commitment only because they are being pushed. This sabotages the entire initiative from the beginning and the effort fails. That sets up a negative vicious circle that reinforces the fears and then re-starting becomes even more difficult. It is essential in all change initiatives, especially big dramatic ones to ensure that you start with some success, however small. Without that the change will almost certainly fail. So also, in this case. The meeting ended on this apparently upbeat note, but I could see that nobody except myself believed what they had heard. My offer to take responsibility for failures proved to be the catalyst they needed to give my initiatives a fair chance to succeed. And as they say, the rest is history.

The fact was that at the time I said it, even I did not believe I could do it. But what choice did I have? My career was dependent on succeeding at Ambadi. The Top Management of our company constantly spoke about their policy of merit-based career progression. For someone like me who was the youngest manager in the company, this meant a great deal because if promotions were given based on seniority as was the norm in plantation companies, I didn’t stand a chance of getting my next promotion in less than six to eight years. And I simply did not have that kind of patience. My only chance for career growth was in creating such amazing results in Ambadi that I would be selected on the basis of merit when the time for promotion came.

Unfortunately, life does not always go according to plan. We created historic results, but I did not get the promotion I expected because the rule was conveniently changed to seniority when the time for promotion came. I left the company and ended my career in plantations. I started a career in management consulting and training that has led me across the world and given me the kinds of rewards, financial and otherwise, that I could not possibly have dreamt of had I remained in the plantations. Our ‘failures’ sometimes do more for us than our successes. That is something that my life has taught me many times.

Absolutely delightful. Beautifully composed are articulated. Superb reading!

I could not have a read this article at a better time. So true – leadership is content independent. This article has revitalised the need to look at the workplace more holistically and own that you can change. I relished the way Sheikh handled the staff meetings and understanding the people in context of their lives. For me, this is a takeaway for managing the school in context. Thank you. I am pleased to say that these articles on leadership and management leverages my skills in the school and therefore, the article has credibility beyond the amazing anecdotes. The attention… Read more »