How do you tell if a person is really from Hyderabad?

Take a Hyderabadi anywhere in the world and ask them where they are from and they will say, “I’m from Hyderabad.” Notice, they will not say that they are from Andhra Pradesh (God Forbid!!) or even from India. But from Hyderabad. And that will be pronounced properly; Hai-dara-baad. Not Hydra-bad. Once you pass this test of allegiance, you will be embraced and welcomed into their homes like a long-lost brother, with the warmth and hospitality that this city is famous for.

Let me start by dispelling a doubt that many people have. Hyderabad is not the name of a city. It is the name of an attitude, a sense of identity, a culture, a tradition. It is the name of the proverbial rope which burnt a long time ago but the twist and power of which is still visible in the ashes. It is the name of the indomitable spirit; of people whose lives were turned upside down overnight; of a people who lost everything they had except their indomitable spirit.

These people stood up from the ruins of their homes and lives to build a name for themselves on the global landscape of the world. It is the name of the peculiar aura of an independent nation, which lost the struggle to remain independent politically, but whose aura remains to this day, most visible in the attempts of the victors to gain legitimacy and honor by associating with the vanquished. It is this Hyderabad about which I write. A land changed and changing. Yet a land lasting and constant.

One evening when I must have been about 15 or so, I recall thinking about Hyderabad, sitting on top of one of the famous boulders of Banjara Hills, behind Chiran Palace, looking westwards at the setting sun as it extinguished its fire in the lake at the foot of Golconda Fort. The home of the founder of Hyderabad. In those days you had an uninterrupted view of Golconda Fort and the Qutub Shahi tombs with no sign of human habitation all the way to the fort. All I could see and hear were magnificent peacocks mourning the passing of the day, partridges and quails heralding the night, hares seeking the safety of their burrows and once, a leopard stalking majestically along, pretending that nothing else existed except himself.

Sitting on top of one of those boulders, I remember asking myself, “What stories this rock could tell me if only it could talk?” It would tell me of the hopes of kings, their desire to immortalize themselves in tombs if not in life. A surfeit of energy and strength led to the situation where I would walk from Sanathnagar where we lived to the rocks behind Chiran Palace, simply to sit on them and watch the wildlife and sunset. It is amazing to recall that in those days (1965-75), once you left the road and took off to the right at a tangent opposite St. Theresa Hospital in Erragadda towards Banjara Hills, which you could see in the distance, there was no habitation in between. I would be walking through fields and cultivation or simply the scrub vegetation of the Deccan Plateau all the way. This consisted of wild Seetaphal (Custard Apple – trust the British to give such a name), some Lantana, wild Toddy Palms, and the occasional Neem. The ground was extremely hard, and sunbaked, cut by gullies through which rainwater flowed and ensured that the land around them never really got the benefit of the little rain that did fall. Black granite outcrops dotted the land, culminating in Banjara Hills, which was the high point. This ridge sloped down the other side to the plains before rising again, a sharp, steep granite wall on top of which sits Golconda Fort. This part of the Deccan Plateau was characterized by huge granite rocks balanced apparently precariously on needle points, granite castles with huge portals leading into caves and defying the imagination about how they were created. The rocks used to be a significant part of the landscape, indicating volcanic activity in the past. Thousands of years of wind and water erosion cut these strange shapes alive today, unfortunately, only in the memory of the generation that was fortunate enough to see them.

Today most of them have disappeared into the foundations of concrete and glass buildings and grotesque houses which are our hallmark of progress. Testimony to our non-existent sense of history, heritage, and beauty is our willingness and ability to blast and destroy the work of millennia of creation because it is convenient for us to build our own horribly ugly dwellings and workplaces. These balancing rocks were the signature of the Deccan; gone forever. Fortunately, they were still there in my childhood and many an hour did I spend watching not only the sunset, but peacocks perched on these rocks or partridges and hares scurrying at their base, to all of whom, these were home. I remember sitting in some of their caves, first having thrown a few stones inside to check if there was anything dangerous inside. Rather a foolish thing to do seeing that to come out straight at me would have been the only way for that animal to get out if it had been there. What could have been there? In those days it could have been leopards or even more dangerous, Sloth bears. But fools are protected and so was I and did not encounter any angry bears.

Not as a measure of nostalgia, but to recall things as they were – if you drove from Sanathnagar towards Kukatpally, all habitation ended at the railway gate. Then there was Kukatpally village – yes, village – immediately after which all habitation ended once again almost all the way to BHEL and Patancheru. Between Kukatpally and Patancheru there was scrub jungle with all sorts of wildlife and birds. If you drove towards the city from Sanathnagar you passed Erragadda with St. Theresa Hospital and the famous Mental Hospital for which Erragadda was known, then you came to the ESI Hospital on your left and the TB Hospital on your right. The TB Hospital was Nawab Fakhrul Mulk’s Dewdi (palace) in which he lived until he built another one on the hill opposite Husain Sagar, called Eram Manzil. This was as a friendly wager between him and Nawab Vicar ul Umra, the Prime Minister of Hyderabad State, to see who would build a bigger and more beautiful palace. Nawab Vicar ul Umra built Falaknuma Palace and Nawab Fakhrul Mulk built Eram Manzil. Immediately after the TB Hospital is the tomb of Nawab Fakhrul Mulk, a beautiful stone building on your right. In it are interred him and his wife. There is a story that he was so much in love with her that after she died, he continued their custom of having afternoon tea together by sitting at her graveside. One cup of tea would be placed on her grave, and he would have his cup and talk to her and once done, would take her leave promising to return the next day.

After the tomb driving less than half a kilometer on your left were 6 government houses for IAS officers, built in typical government style, concrete structures painted pink. Behind these houses was the area with plots marked out and one or two houses that would become Sanjeeva Reddy Nagar. If you left the road opposite the IAS officers’ quarters at right angles, you would be walking through fields and scrub land all the way until you climbed the slope to the top of Banjara Hills and came out near the Green Mosque on Road # 3. There was a dirt track from there to the big black wooden gate of Chiran Palace which was always shut, and the road ended there. The wall of Chiran stretched away on either side of the gate without any road or any habitation until on the left you came to the end of Road # 12 where the first house you came to was Fatima Manor.

Going to the right as you face Chiran’s main gate you could go along the wall walking through scrub forest and over rocks until you rounded the corner and then you could gaze clear across the countryside, rocks, clumps of trees and scrub bushes to first the Qutub Shahi tombs in the foreground backed by the imposing structure of Golconda Fort on the ridge behind. I walked all that way from behind Chiran Palace to the top of Golconda Fort twice, not encountering anything or anyone all the way until I came to the village near the Fort. Impossible to believe today, less than thirty-five years later, when thanks to the buildings, you can’t see the tombs or the fort from Chiran Palace, which is now called KBR Park.

After Sanjeeva Reddy Nagar, if you continued towards Panjagutta, habitation ended once again and you passed through rice fields on either side of the road, dotted with wells and tamarind trees. Then you came to the turning on the right for Yusuf Guda. At this exact point where the road to Yusuf Guda branched off right from the main Ameerpet – Sanathnagar road, on the left was a huge old well with a tamarind tree alongside it. Today a shopping mall stands on it. Then you proceeded through some more farmland until you came to the Ameerpet crossroads. There was Natraj Medical Hall at the junction and a road branched off to the left towards Begumpet. Natraj Medical Hall is still there. If you continued straight onwards you passed through some more farmland and the beginnings of Srinagar Colony, until you came to a series of shops on either side of the road selling bamboo poles. These bamboo poles were used to build scaffolding to construct multi-storied buildings. That brought you to the Panjagutta Chowrasta (crossroads) with its Police Station and the road going off to Banjara Hills on the right and to Secundrabad on the left. A little way ahead was Picnic Bakery (still there) opposite which, believe it or not, were some more rice fields. The Nizam’s Orthopedic Hospital was being built and the Masjid Bee Sahaba was in its original form with the tomb of its builder behind it. The ugly shed that now stands in front of it, didn’t exist. We used to pray Taraweeh in this masjid. There was a small Janimaz (sajjadah/musalla – prayer mat) for the Imam and one strip behind him which could hold about 20 people in the row. All the rest had to stand on the cold stone floor. In summer that was very pleasant. In winter, it wasn’t. After Isha Salah they would turn off all the lights – economy, not theology – leaving only one small bulb to keep us away from total darkness. Then the Imam would begin Taraweeh and finish the entire proceedings of 20 Raka’at in 45 minutes and we would all go home.

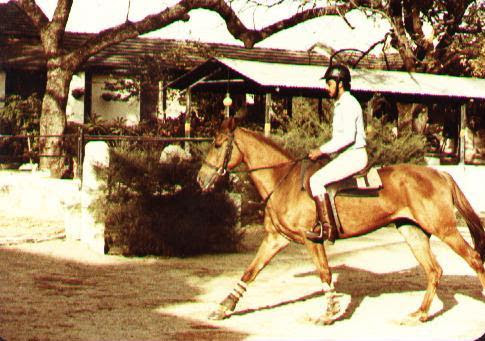

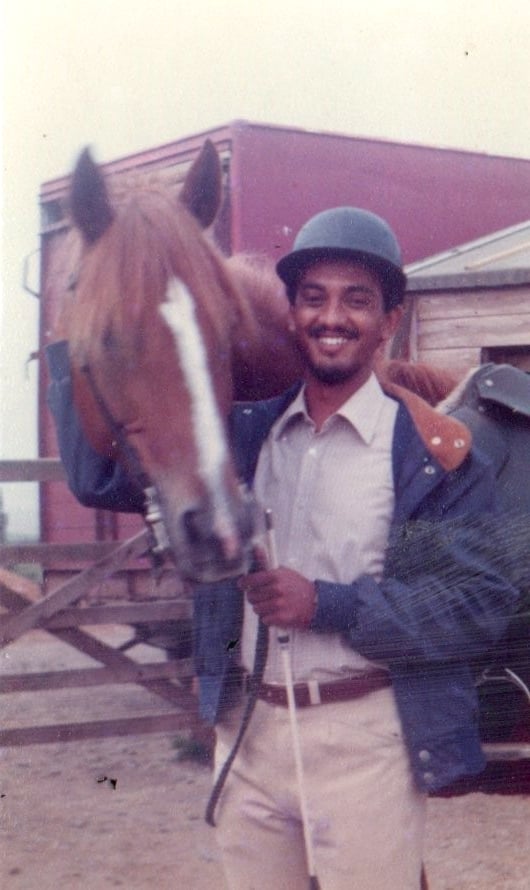

The rocks and slopes of Banjara Hills were very familiar ground to me. I had a friend, a German scientist who worked in ICRISAT and owned horses. He lived in the house called Fatima Manor which I mentioned above. On alternate days, I would ride his horses with him and sometimes, have breakfast with his family. Rahul, who was also a friend of this family, would join us sometimes. Some months after I met my scientist friend it was time for them to go on vacation to Germany. The big question was the horses. Who would take care of them while the family was away for a month? My friend asked me if I would be willing to look after them and ride them regularly. That was like asking me if I wanted to go to heaven. So, it was agreed and off they went, leaving me in charge of their horses. To this day I can clearly recall how delighted I was at this.

I would go religiously twice every day; in the morning to ride the horses and in the evening to ensure that they had eaten and that all was well for the night. This meant a ride on my scooter of more than 40 kilometers daily, but who was complaining? One day, Rahul also came in the morning, and we decided to go on a long ride. In those days (1970-72) as I mentioned, Fatima Manor was the end of habitation on this road. Then the road wound along as a small track until it ended at the wall of Chiran Palace. There was no road around the palace. If you wanted to go to what is today the Jubilee Hills crossroads, you would have had to go cross country. If you came out of the gate of Fatima Manor there was open land stretching before you all the way to the Golconda Fort and its surrounding habitation. There was no habitation until you reached that neighborhood. In the evening you would hear partridges calling and quail would sometimes rise suddenly from under the feet of the horses, startling horse and rider. Peacocks from the Chiran Palace grounds would announce the setting of the sun. In the distance you could see Bala Hisar, the topmost apartments of the king on Golconda Fort, the same sight that the scouts of the Qutub Shahi king would have seen 400 years earlier from the backs of their horses. History was never too remote for us.

The day that Rahul and I chose to do our long ride started early. We reached Fatima Manor at the crack of dawn and saddled up the horses. Once the light was strong enough to start, we mounted up. The horses were naturally skittish early in the mornings, which are cold, and resented being pulled out of their warm stables. But as we walked them along the path, they gradually warmed up and pulled at the bit to go faster. On a whim Rahul and I decided to race and galloped into the fields adjoining the path. As we rode, we came upon a low stone wall, which I decided to jump. I gathered my mare, held her close, and pointing her at the wall gave her, her head and up and over she went. But the gelding that Rahul was riding had never been schooled in jumping and balking at the idea at the last moment, landed squarely on top of the wall and scrambled over. Rahul was almost thrown off. This was a disaster. I rode back to where they were both standing still. The gelding had blood running down his legs and, on his belly, where he had landed on the wall and badly scraped himself on the stones. My heart almost stopped, seeing what had happened. All kinds of thoughts of the different ways in which I was sure that the owner of the horses would kill me, very, very slowly and painfully, went through my head. I could hardly breathe.

Here I was, having been given this awesome responsibility to take care of my friend’s horses and I had just succeeded in almost killing one of them. The thought that it was Rahul and not I, who had been riding that gelding did not even enter my head. I was the leader and so I was responsible. Period. Of course, this incident put paid to our plans for the long ride. We returned home, which was close by, walking and leading both horses all the way. I then examined the gelding thoroughly and discovered to my great relief, that he did not appear to have broken any bones. The wounds were all superficial, and though there could be danger of infection, they were not life threatening.

I washed the wounds with warm soapy water, rinsed them with clean warm water and then cleaned them with Hydrogen Peroxide. I then dusted them with antibiotic powder, gave the gelding an antibiotic injection, and we both prayed for the best. Our prayers were answered, because with regular and careful nursing, in about 10 days, and long before the owner returned, the gelding was as good as new. Big lesson in handling responsibility.

ASK yawar, Well written, I read India to Indies. I want to read your biography, excluding the experiences you already narrated in India Indies. –Hyderabadi Bhai qadir.

Please read In a Teacup. Also read An Entrepreneur’s Diary.