Hyderabad Public School and other matters

I grew up in Hyderabad in the late 50’s and 60’s – a planet away from what it is today. I went to one of the best schools in the country, the Hyderabad Public School, as a boarder when I was 6 years old. People felt sorry for me to have to live away from home at such a young age, but I was thrilled.

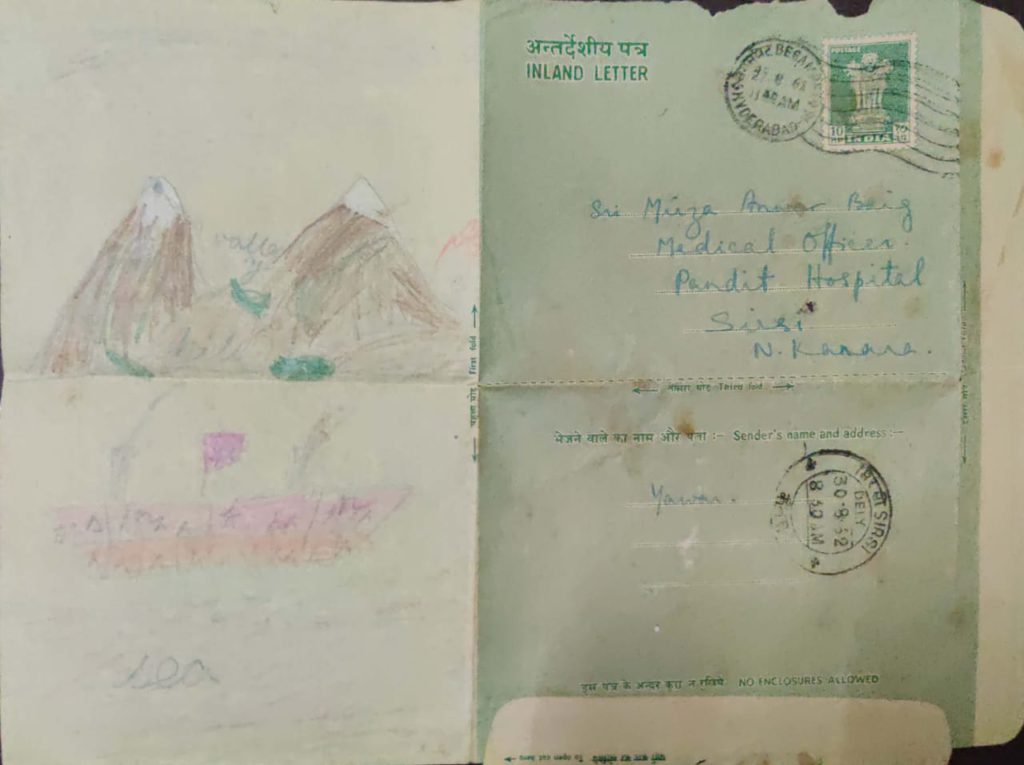

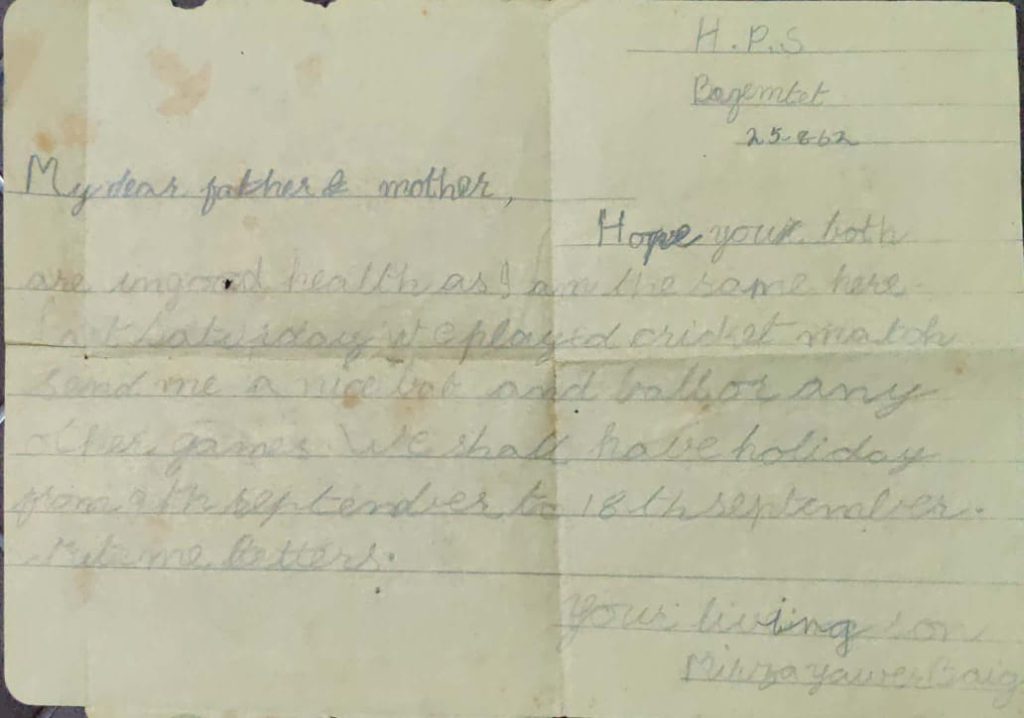

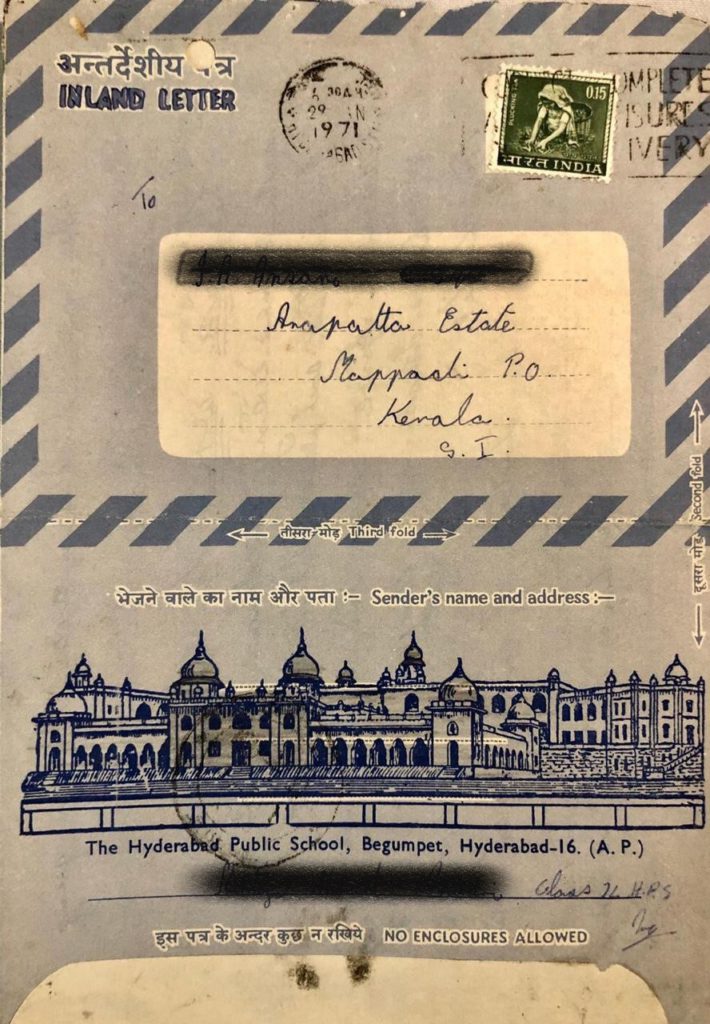

One year later, when I was six, I was enrolled into the boarding at the most famous school of the time, Hyderabad Public School. Earlier known as Jagirdars College, it was established in 1923 by the Nizam of Hyderabad, HEH Mir Osman Ali Khan, the Founder of Osmania University. The Hyderabad Public school was built on land donated by his aunt, Begum Vicar ul Umra (her husband, Nawab Vicar ul Umra built Falaknuma Palace) as a school exclusively for the sons of the nobles and aristocrats of Hyderabad State. It was renamed as Hyderabad Public School in 1951. It sits in the middle of the city on a hundred-acre campus with buildings ranging from the Qutub Shahi style of architecture to our latest nightmares in RCC, Modern Indian Horrible. Proves that you do not have to be ignorant to be a philistine – the modern buildings were sanctioned by the Board of Governors of the school about whom it is believed that they were educated. My earliest memories as a little six-year-old in boarding are not all pleasant. I was inveigled into agreeing to go by being told that I would be able to have bread, butter, jam and omlette every day for breakfast. I discovered however that on most days we got oatmeal porridge with milk and sugar or honey and a boiled egg. We used to be bathed in a way reminiscent of washing sheep before shearing. We would be herded into the bathroom, stark naked, then hosed down with a hose pipe fitted with a shower-head. We would get a few minutes to soap ourselves and then we would be hosed down again. Of course, all of us six and seven-year-olds thought it was great fun and this was borne out by the volume of sound emanating from the showers while this communal cleaning exercise went on. Every week we had to write to our parents on Inland Letter forms. The letters would be taken from us, read, corrected, addressed, sealed, and posted (mailed) by the class teacher.

Our school was famous enough to have its picture on the back of these Inland Letter forms.

What made things worthwhile were two people – my housemistress Mrs. Lamoury and my English teacher, Mrs. Anwar Hussain. They were my foster parents as it were, and Mrs. Anwar Hussain’s son Nizwer was in my class and so all was well. Last year (2011 December) Mrs. Anwar Hussain called me and gave me a family photograph which my father had given her when I had joined school in 1961. What was amazing for me was not that she had kept that photo for 50 years, but that she asked me about my brother and sisters, who are in the photo, by name. I was one of a million children who passed through her hands but the thought that she remembered me, and my family sets her apart as a teacher of teachers.

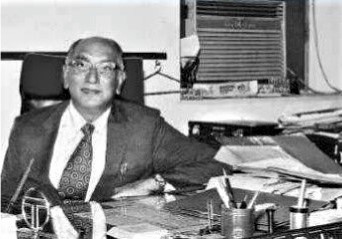

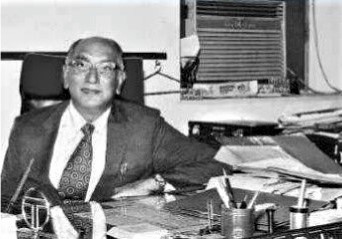

That was a different generation from the present one. Cut to 2000. I had just returned to Hyderabad from America and decided to visit my old school. I had no idea if any of my teachers were still there. I had graduated from school in 1972 and this was 2000. I walked into the main administrative block, the beautiful Qutub Shahi building with lovely domes and arches called the Shaheen Block and was greeted by the peon sitting at the door of the principal’s office. I asked him, ‘Who is the principal?’ He said, ‘Sambasiva Rao sahib.’ I was delighted to hear this because Mr. Sambasiva Rao had been my class teacher in senior school – 1965 to 1972. We remembered him mainly for his theatrics when he was angry with us; he would pull out his belt and hold it high above his head stretched in both hands and thunder in his Telugu accented English, ‘I will phowder you.’ But we all loved him as he was a wonderful man. I said to the peon, ‘I want to meet him, is he free?’ He replied, ‘Jee Saab he is free. What is Saab’s name?’ I said, ‘Don’t tell him anything. I want to surprise him. I am an old student of his.’ The man allowed me into the office. Imagine my astonishment when I walked in and Mr. Sambasiva Rao looked up from his desk with a big smile on his face and said, ‘Aray Yawar, come in, come in. What a lovely surprise! How are you?’

Here was a man seeing me after twenty-eight years, not having seen me in the interim, and he recognized me instantly. When he saw the shock on my face, he said something which has stayed with me ever since. He said, ‘Why are you surprised? We used to love our children. I remember you and all your friends.’ And then he proceeded to remind me of the different boys who were in class with me and of the pranks we played. What stayed with me were his words, ‘We used to love our children.’ I wonder how many teachers can say that today.

We had two Principals during my time in school. Mr. K. Kuruvilla Jacob for most of the time and then Mr. M. C. Watsa (the Canadian billionaire Prem Watsa’s father), in my final year in school. Both were remarkable men. Mr. Kuruvilla Jacob was a legend in his own lifetime. A man who taught me about leadership before I knew the word. Let me tell you three stories about his leadership style as I experienced it.

The school followed a system where students who passed with more than seventy percent were given a First Class certificate and those who passed with more than eighty percent were given a Distinction certificate. The certificates had the name of the student printed on them, and were formally presented to the children in the morning Assembly by the Principal. I liked school and studying and always used to get a Distinction card in every term. When I was in the 8th class (grade), I fell seriously ill with jaundice and then had a relapse so I could not attend school the whole term (three months). My father obtained special permission for me to study at home and take the exam. I did that, but thanks to my illness and perhaps some lack of discipline in studying, I only managed to get a First Class that term.

Duly, in the Assembly, my name was called, and I went up to take my certificate from the Principal, Mr. Kuruvila Jacob. He gave me the card, smiled, and shook my hand and said, ‘What Yawar, tired of getting Distinctions, is it?’ I mumbled something and fled. But I can assure you that I never got anything but a Distinction thereafter.

One day, I was sitting in class waiting for the morning recess bell to go off. My seat was by the window looking out over the courtyard across which were the toilets. To my amazement, I saw Mr. Jacob walking into the toilets with a bucket with cleaning brushes in it. A word about how Mr. Jacob looked and dressed is necessary to appreciate the reason for my surprise. Mr. Jacob was a tall and dark man who always wore white on white. He wore a white bush coat – patch pockets, half sleeves on white trousers and shining black shoes. His clothes were always sparkling white, starched, and ironed to a knife-edge. You could cut yourself on the crease of his trousers and look at your face in his shoes. Here was this man in those clothes walking into our toilets with a bucket and toilet cleaners.

I dug my seat mate in his ribs and gestured but before his eyes popped out of his head, the bell rang, and we all trooped out silently and stood before the toilets. What did we see? Our toilets, like I suppose the toilets in most boys’ schools, had their walls festooned with rather smelly poetry and prose, to put it politely. What we saw was Mr. Jacob, cleaning the walls of the toilets. He worked silently, ignoring us, spraying the cleaner on the walls, and then brushing them clean and washing them down with water which he had carried in the bucket. When he finished a few minutes later, he picked up his bucket, finally looked up at us, smiled, and walked away. He did not say a word. Not one word. He just smiled at us and walked away, back to his office. We simply stood in silence and watched him disappear. I was in school for four years after that incident and can vouch for the fact that nobody ever wrote anything on the toilet wall again. Interestingly, the phenomenon of writing on the walls of the toilets was universal – all toilets had this graffiti. Mr. Jacob washed only one toilet. But suddenly all toilets were clean, and no graffiti was ever written on them again. And remember, as I said, not one word spoken. I realize today that what he did was as much theatre as it was cleaning, maybe even more theatre than cleaning, but the impact was powerful and permanent. Leading by example always is.

The third story is again a personal one. We had a tradition that once every term, we were invited to eat lunch with the Principal at his Residence. I suppose the idea was to civilize us because the normal scene in our dining room was quite lively with flying bread, chairs pulled back at the final moment of someone’s descent into them, and other such interesting activities. Of course, our House Master and Mistress, Mr. and Mrs. Sardar, made us pay the price if they caught us, but that only made the entire matter more exciting. The lunch in the Principal’s Residence was another matter. Here misbehavior was a capital offence and so we would all be on our best behavior. The Principal’s Residence was a palatial house in spacious grounds built like a plantation bungalow with a wide veranda at the front, overlooking a lawn that ended at the low hedge which separated the orchard of fruit trees from the rest of the garden. On the far side was the vegetable garden while the drive curved round the house to the garages.

On the day in question, my class arrived for lunch but discovered that Mr. Jacob had not returned from office yet. Mrs. Jacob, with her experience of schoolboys, wisely told us to wait for him on the lawn. So, we deposited ourselves all over the lawn, waiting and hungry. As I lay on the lawn on my back, contemplating the sky, I happened to roll over and noticed that the guava trees in the orchard were full of fruit. Green and half ripe guavas on almost every branch. The speed of light is slower than the speed of thought and the speed of thought is matched by the speed of action when it comes to a combination of desire and hunger and so before I knew it, I found myself in the upper reaches of the tree. Some of my friends gathered below the tree, waiting for their share of the bounty and everyone was focused on me and my expected exploits in de-fruiting the tree in record time.

Suddenly we heard the deep voice of Mr. Jacob, ‘Boys, come for lunch.’ I almost fell out of the tree in fright. My first thought was that I would be expelled and then killed very slowly by my father for having got myself expelled from one of the best schools in the country for stealing from the Principal’s garden. This was sacrilege, like stealing the idol from a temple. And on top of that to be caught red handed by the Principal himself was to add insult to injury. ‘First of all, you are stupid enough to go and steal from the Principal’s garden and then you are even more stupid to get caught by the Principal himself.’ I could hear the statements as I died slowly. I silently cursed my friends for not warning me that Mr. Jacob was on the way home, but I guess everyone was so engrossed in the guavas that nobody noticed. Anyway, I dusted my uniform and we all walked slowly to the house. I tried to become very small and hide but that did not do me much good.

As we went up to the house, I saw a strange sight. There was Mr. Jacob standing on the veranda with two baskets of ripe guavas at his feet. As all of us stood silently before him, he said, ‘Come boys, take some guavas.’ We looked at one another and then one of us started the movement and picked up a fruit. ‘Take another one. One is not enough,’ said Mr. Jacob. I thought I could still disappear, but he said, ‘Yawar, take some guavas.’ It is a good thing that I am not white otherwise I would have glowed red like a traffic light. Then he said, “Isn’t that better than what you were picking in the tree, Yawar?” he asked me.

At that point I would have agreed to anything he said. I picked up two lovely ripe guavas and then he said, ‘Come let us have lunch.’ And that was that.

No punishment. Just one question that taught me a lifelong lesson: treat people with dignity when you could have humiliated them, and not only will they learn the lesson, but be grateful to you for life. Mr. Kuruvilla Jacob is a man who I will always remember with respect, affection, and pride. It was an honor to be taught by him. A real teacher. I was a very fortunate boy. Amazing man! A leader the like of which I have not seen. A leader who taught me how to lead without speaking a word. A leader from whom I hope I learnt something and whose memory I bless every time I think of him.

Regretfully, Mr. Jacob left the Hyderabad Public School but, in his place, came another wonderful Principal, Mr. M. C. Watsa. Mr. Watsa was a quiet man but ran the school like clockwork. I was in school only for a year while he was Principal but had one encounter with him which I remember with great warmth and affection. I was in my final year and very confused about choices that I needed to make with respect to my college. I don’t recall now how it came about but one day, Mr. Watsa called me to his office and said, ‘Yawar, when you walk down a poorly lit road at night, sometimes you see shadows which look very frightening. But if you keep walking you come to the shadow and realize that it is only a light pole or something like that. The shadow looked frightening, but the reality is something we can deal with.’ I remember this advice and have applied it in many decisions in my life. What I wonder at is how a Principal of the school had the time to speak to a boy like that.

Teaching and schooling were obviously something different from what seems to have become the norm in India. How teachers saw their roles was very different.

School was a wonderful experience. We lived in a time where values of honor, friendship, and loyalty were not laughed at. One incident which I recall was when the new science block had just been built. This was a hideous rectangular concrete structure, built cheek by jowl with our beautiful Qutub Shahi main building with no regard for architectural design compatibility or concern about perpetrating esthetic violence. When the building was almost complete our class was the first one to be allotted a room in the new block. The room was on the first floor with big windows and good lighting. The toilets however were not functional yet and so the doors had been barred with 2×4 flats nailed across the door. One day during recess, three friends of mine and I were at a loose end, and they dared me to break into the toilet. I accepted the silly dare and slammed the door with a roundhouse kick. There was a tremendous crash and the door burst open. That alerted the watchman who was at the entrance, and he ran up the stairs. We scurried into our class where the rest of the boys were gathered. The watchman saw what had happened, not who did it. He reported the matter to Mr. Sambasiva Rao, our class teacher. This was a serious offence which could have got me into serious trouble, maybe even suspended or expelled, so I was very apprehensive.

Mr. Sambasiva Rao came into the class and demanded, ‘Who did this?’ I was silent as was the whole class. He said, ‘I am giving you three days. If you don’t tell me, who did it, I will punish the whole class. You can come and tell me who did it if you do not want to speak in front of everyone. I will not reveal the name of the one who tells me. This is for the good of the school. You should not hide whoever did this. You have three days and then you are all in trouble if you try to save whoever did it.’ Then he left. I said to the guys, ‘Look, I am going to tell him I did it. I don’t want you all punished.’ They refused. They said to me, ‘You shut up. No need to volunteer.’ There were 30 of us in class. But for three days, the class teacher waited in vain for someone to ‘sneak’ and tell him who had done the deed. On the third day he came to class and said, ‘I appreciate your loyalty to your friend, whoever he is, but you are all in trouble. I am assigning you extra PT for three days.’ That was a punishment we all hated because it involved running around the periphery of the football and hockey fields several times in the afternoon. Hot, boring stuff. So, every afternoon for three days, the entire class ran, cursing me as we ran, practicing their vocabulary, and teaching me some new words – but not one boy reported me to the teacher. There was not even any discussion about the matter. It was just something which was understood and respected. Such were my friends. I would have done the same for any of them. It did not occur to any of us that we could ‘sneak’ about a friend to the teacher. It simply was not done. That was all.

We had a ritual of a medical examination, every term. The doctor was a man by the name of Dr. Perumal. He lay in wait for us in the hospital, which was behind the main school buildings, near the baseball field from which you could see the Begumpet Airport runway which our land bordered. We would go class by class, all lining up in the veranda before his office. He would call us in one by one and do the same thing to everyone:

‘Put out your tongue.’

‘Look up,’ as he pulled down the lower eyelid.

‘Pants down,’ and when we were standing before him bare bottomed, ‘cough’.

‘Okay’, you can go. What he was looking for I never discovered. Maybe he thought something of value would drop out if we coughed. But nothing happened.

In the evening after school, we would all gather in front of the Shaheen block, the main administrative building to wait for our pickups. One of my classmates, Som Bhupal and his younger brother Keshav used to be picked up by their mother so we would all hang out together until their mother came. One day while we waited some of us started playing hockey and Keshav was hit in the head with a hockey stick. He started bleeding profusely and we panicked. I picked him up and ran with him all the way to the school hospital not realizing that both his and my shirts were soaked in his blood. The wound was not serious, but scalp wounds tend to bleed a lot and look worse than they are. In the hospital, he was bandaged and given a shot of tetanus. While this was going on, I thought I’d better go to where their mother came to pick them up and tell her that the brothers would be along shortly. So I went. She was already there, so I greeted her and said, ‘Aunty we had to take Keshav to the hospital because he got injured.’ I saw a look of horror on her face and suddenly realized that the top half of my T-shirt was soaked in his blood. I must have been a horrific sight and god knows what she thought had happened to her son. I hastened to reassure her that he was alright and as we were talking both brothers returned, and all was well.

I used to walk to the bridge just after Begumpet station to catch the bus home to Sanatnagar where we lived. The bridge was across a lovely stream which today is a sewer. Further upstream there was a small spill dam which created a small lake bordering our school grounds. With thick rushes along the banks harboring Egrets, Moorhens, Jacanas and in season, Pintails, Mallards and Brahminis. Brahminis and Comb ducks (Nakta) are not migratory, and we usually had a couple of pairs in attendance. The lake was a lovely place to be at. We used to row in it occasionally. There was a cross country running track along the bank of this stream. The track went along all the way to where our school land ended and then we took a right and ran along the boundary between the Begumpet airport runway and our school, through rice fields until we came back to the main Begumpet road. The water in the stream was pure, it had fish which we used to try to catch on Sundays. We were not allowed to swim in the river, but the water was good for it, had we been permitted. Today it is dead, filthy, and poisoned with industrial effluents.

The bus is another story. The return fare to Sanatnagar from Begumpet in the 60s when I was in school was less than one Rupee. I would get one Rupee a day which would leave me with a few paise with which I would buy two mirchis every evening just before getting on the bus. A mirchi is a green chilli, with a sour chutney in its belly, batter fried. Hot and absolutely delicious. Sometimes there would be money for an ice also. An ice was made as follows. The ice maker would have a huge block of ice on his pushcart. He would shave off some shavings using a carpenter’s planer. Then he would put them into a small glass tumbler and from bottles that contained various colored liquids he would pour measured quantities onto the ice shavings. He would mix them all and then he would put a spoonful of another brown pasty liquid and give you the most delicious ice you could eat. So, the fire of the mirchis put out by the cold and sweet of the ice and then onto the bus. Other passengers looked at us in our HPS uniforms with envy. One day I heard someone saying to his companion, “It is a very expensive school. The fee is Rs. 100 per month.”

On Saturdays when we had school for half the day, I would sometimes stop over at our friends the Agarwals in Ameerpet for the afternoon. Their father, D. P. Agarwal was the head of Hyderabad Allwyns where my father was the Company doctor. He had three sons, two of whom were my brother’s and my classmates. Chandramohan, my classmate and I, after a lunch of parathas with ghee on them and delicious vegetarian dishes and sweets, would go with their buffaloes for a swim. Their house was next to a building called Lal Bangla in Ameerpet, opposite what is now Green Park hotel. There was no Green Park hotel but instead all that area was open fields with a huge open well in the middle of it that overflowed and became a large tank. The buffaloes were the famous Murrah breed from Haryana and Punjab and famous for being excellent dairy animals. We would ride on the buffaloes in our underwear. They would cross the road and head straight for the tank where they would enter the water and swim over to the other side to a place that they liked to wallow in. We rode on their backs or hung on to their horns or ears or tail, ensuring that we did not part company from them midstream.

On our return we would help the caretaker milk the buffaloes, sometimes directing a jet of creamy milk directly from the teat into our open mouths. Having ridden the buffalo into the water and back made you immune to the buffalo smell of fresh milk straight from the udder. Then we would bathe, change, and have dinner; again delicious vegetarian Rajasthani/Marwari food, and I would return home.

Our teachers were wonderful people. We had Mr. Jim Bray who was from East London, I believe, who taught us English language, mathematics, and chemistry. It is interesting how, out of all the years and hours of teaching, some things stand out. What I recall about his teaching style was that he was very keen that we learnt the method of deriving formulae and not simply mug them up which was the preferred method almost anywhere in India and still is to this day. For his papers in the exam, we had to show the whole derivation. And he would give us marks even if we were wrong if we had attempted to derive the formula. This emphasized the importance of logic and deductive reasoning. Another thing about Mr. Bray I remember was that one day he drew a small circle on the black board and said, ‘Inside the circle is what I know. The circumference of the circle is what I do not know. Now look closely, what happens to the circumference when I make the circle bigger? It grows. So, what does it mean about what I do not know, compared to what I know, when I learn more and more? It means that the more I know, the more I do not know. When I learn, all that it does is that it gives me more questions to answer. And as I answer them, I get some more questions. Until I had that information, I did not even know what to ask. Now that I have the information, do I have all the answers? No, I just have more questions. That is why learning is fun. And that is why we must never, at any stage of our lives, consider ourselves to be learned. All that happens is that we have more questions to ask.’ What an amazing lesson to teach a class of twelve and thirteen-year-olds! Today, fifty three years later, I still recall – even see him talking to us in his East London accent, with the powder of the chalk on his fingers.

Mr. Daniel Sam taught us physics. Mr. Tiwari taught us Hindi and insisted that we address him as ‘Sriman Adhyaksh Mohday’. Mr. Sa’adatullah Khan and Mr. Tilmizul Hasan taught us Urdu. Sa’adat sahib was also a poet, and his pen name (Takhallus) was Nazir – Sa’adat Nazir. He loved Urdu and was a wonderful teacher. Mr. Devadattam in his starched whites was our PT teacher. He was a very dark man and looked very striking in his starched whites. His arm was long and strong, and we felt its power fairly frequently. Those were the days when the teacher was allowed to use corporal punishment if he thought we deserved it and Devadattam seemed to think that quite often in our case. Mr. Mathan was another of the PT and Games masters who subscribed to Mr. Devadattam’s philosophy.

The Hyderabad Public School was very big on games and so a lot of emphasis was given to physical fitness. We boarders had morning PT at dawn and then games which were compulsory every day in the evenings after school ended at 4.00 pm. I was never very good at football, hated cricket and never managed to connect racket to ball frequently enough in tennis to be a threat to my opponent. Those were the days when there was only Test Cricket, a test of the patience of the players and spectators. It took all of five days to arrive at a conclusion which today we do in 20 overs. My crowning glory so to speak in football was when I kicked the ball into our own goal during one inter-school tournament. I almost got lynched on the spot and never heard the end of it as long as I was in school. Amazing amount of emotion people seem to be able to put into kicking a ball around a field. However, the lesson to me was clear – if you cannot get the same amount of emotion into it, get off the field. This holds true for anything in life actually – if it can’t make you cry, it can’t make you work.

Passion, no matter how insane it may seem to others, is the key to success. The good news is that it is only those who are involved in a task who need to be passionate about it. So, if you are passionate, get on with it but be sure to get those who are not passionate off the team. That is equally important. I didn’t like any of these games. What I loved with a passion was horse riding and so that is what I did and excelled in. For all those school years, I would spend two hours every morning in the AP Riding Club, grooming and riding horses. Grooming was not officially part of the riding lesson, but I discovered that you made more friends with horses, grooms, and instructors by grooming horses than in almost any other way. That way you got to ride more than one horse for the same fee of Rs. 2 per day which otherwise entitled you to a half hour riding lesson. I managed to do at least four times that thanks to social skills. Very important lesson learnt that social skills are at least, as important as if not more important than technical skills.

One of the things our school did very well was to encourage reading. We had one of the best libraries in the country and we were allowed to spend as much time as we wanted in it. We were taught how the books were arranged; a method called Dewey’s Decimal System of Classification; so that we could find the books we wanted. We had all sorts of books, ranging from fiction to philosophy to religion to history to biographies, nature, ecology, and science. Among the books that I read and which I can still recall are J.R.R. Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings, Atlas Shrugged and several others of Ayn Rand, the whole series of Jim Corbett and Kenneth Andersen, the whole series of Gerald Durrell and James Herriot and almost the whole series of P. G. Wodehouse. I read Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, Dr. S. Radhakrishnan’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita, James Thurber, Alexander Solzhenitsyn. And of course, the great Enid Blyton. I read Romila Thapar’s History of India, Nani Palkiwala’s We the People. Among later readings is Shashi Tharoor’s Great Indian Novel, Conn Iggulden’s entire series on Ghenghis Khan and Julius Caesar and William Dalrymple’s Last Moghul, White Moghuls and Anarchy.

I believe that it is essential to read, both to learn as well as to understand the life and times we live in. Reading is the window into other lives and times which help us to put our own in perspective. We must not be afraid to read anything, nor must we prevent people from reading anything. What we must do is to share learning, question, and extract lessons. Without reading we have no means of understanding others, thereby no means of understanding how to deal with them, influence them or make a positive impact in their lives. Those who are afraid of reading promote ignorance. We were taught to question, not simply to accept whatever we read. We were taught to review and express our own opinion about what the author may have written. Then we would discuss these in class. We were taught to distinguish fact from fiction and allegory and to draw lessons. We also learned to laugh at ourselves and to have a good sense of humor. This seems to be in short supply currently with people taking themselves far too seriously and carrying their sense of offense on a hair trigger. Such people are condemned to a sad, desolate life of loneliness where they take satisfaction in the number of people they criticize or think badly about. For my part, I believe that laughing, especially at myself is very important to my physical and psychological well-being and that it is essential to shun all self-righteous morose creatures who walk around with a permanent bad smell under their noses.

Boarders had to bathe and dress for dinner in our National Dress; Sherwani or Jodhpur coat. I would race up the long stairway to the dorms, bathe in cold water and change and then come down for the study period before dinner. There was no air-conditioning in the world I think in those days, and certainly not in India and not in my school. Neither did we get hot water except in winter. But the weather in Hyderabad being what it is, a cold shower after a hard game of football was most welcome.

As I grew older, traveled the world, lived among people of different races, religions, and cultures, as I faced challenges in my career, relationships, and life itself, as I learned and taught others, the foundation that my school – The Hyderabad Public School – gave me, has stood me in very good stead. That is the hallmark of a great school. It doesn’t just teach children literacy and numeracy, but prepares them for life. That is what The Hyderabad Public School did so well.

I look forward to visiting my school when I am Hyderabad next.

Comments (0)

Comments for this post are currently disabled.

Loading comments...