Sometimes people ask me for the secret of success. We live in a world of fantasy where people want magic formulae for everything. Let me tell you the good news. It is not a secret, but it is a magic formula. Focus + Investment + Consistency. Works every time.

I have given it the acronym, FIKR – K from the phonetic pronunciation of Consistency (Konsistency). As for the R – well, we’ll get to it. Just remember FIKR.

One of the most famous cases of FIKR in action is that of Dashrath Manjhi, a poor villager in Bihar, who literally carved a road out of a mountain. When his wife died tragically, because he was unable to get her to a hospital in time thanks to the fact that he had to go around a mountain to get to the main road, he decided to cut the mountain and build a road. He carved a path 110 meters long, and 9.1 meters wide to form a road through the rocks in Gehlour Hill so that nobody else would need to suffer the same fate as his wife and he had to. It took him, working with a chisel and hammer, 22 years. He did this without surveying equipment or experience, drone photographs or any technology, explosives or heavy equipment. You can read more about him here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dashrath_Manjhi

What was his secret? Focus + Investment + Consistency. Works every time.

In 1983, I had just returned from Guyana and joined the tea planting industry in the Anamallais. On my first annual vacation, I attended a two-week residential, experiential learning workshop on Applied Behavioural Science by the Indian Society of Applied Behavioural Science (ISABS), in Jaipur. I found it very beneficial and was impressed by the potential to help people that lay in this line of work. I was particularly impressed by Mr. Aroon Joshi whose facilitation enabled me not only to understand myself better but to resolve some issues which had been bothering me. Aroon has been my dear friend and mentor ever since. The long and short of this was that I decided that I would make training, my profession. I was a tea planter. And I wanted to make a career in training. Sounds crazy. It was. How did I do it? That’s what I want to share with you. I hope you will be able to benefit from the lessons I learnt in my life.

Before I go into the how, let me tell you what I did since then, so that you have a complete picture in your mind. From the time you saw a young tea planter, sitting on the floor in an ISABS Lab (that is how it worked), agonizing over his work relationships, you would have seen him single-mindedly focused on learning how to train, to taking some very hard decisions and risks which would have left many, freaked out. You would have seen him speak to his first client and stake his reputation in his pitch. You would have seen him succeed and fail but succeed more and never fail at the same thing twice. In short, you would have seen him learning. Learning all the time. Enjoying learning, which enabled him to take ever higher risks. You would have seen him challenging himself and doing things which most people in any line of work, never do i.e. write thirty-six books. Today, I have trained over 200,000 people on three continents from practically every nationality, race and walk of life.

From where I started in training, I specialized in leadership development. That is what excited me. To see people come in, looking like something off the clothesline and walk out, straight and tall with a glint in their eye and to know that I’d had something to do with that. Over the years, now almost 40, several times I have had people come up to me in an airport or in a restaurant and say, “I don’t know if you remember me (I almost never do) but I attended your workshop and it changed my life.” I consider myself fortunate that this has happened to me more than once, because even once is enough for a lifetime, to know that you made a difference to someone.

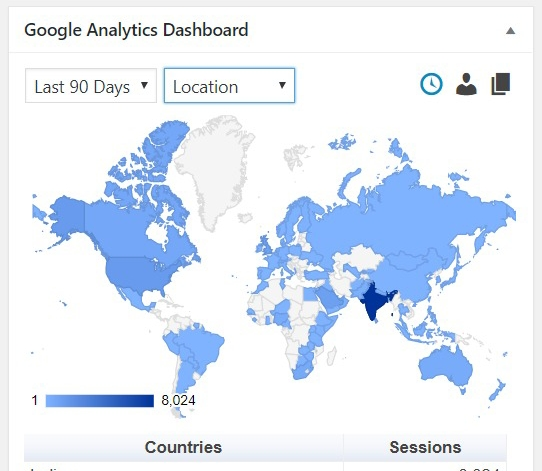

In leadership development, I super-specialized in family business consulting (wrote, The Business of Family Business) and entrepreneurship development (wrote, An Entrepreneur’s Dairy) and then started a podcast called, “Leadership is a Personal Choice”, (wrote another book by that name) which has a global footprint, from China to the Americas with Asia, Europe (except Greenland) and Africa in between. Maybe there is nobody listening to my podcast in Greenland because Trump wants to buy it and they’re all holding their breath.

How did this happen? Focus + Investment + Consistency. Works every time.

To return to 1983, I made my way back to the Anamallais from Jaipur, taking the Pink City Express to Delhi and then the Rajdhani Express to Chennai. Then the Nilgiri Express to Coimbatore and the bus ride to Valpari, up the Aliyar Ghat’s forty hairpin bends. Tamilnadu Transport Corporation bus. Nothing fancy. The big task in it being to ensure that you get a window seat but stay upwind of anyone with motion sickness. That last one being a matter of luck, more than anything else. All through that journey and every waking moment thereafter, my single thought was, ‘How can I become a leadership trainer?’

The first thing that I did was to write on a large sheet of paper, with a thick marker, “In the next five years, I want to be a globally recognized leadership trainer.” Hindsight tells me that I was a bit off as regards the time but made good the rest of it. The timeline was very useful because it helped me to keep focused and gave me a sense of urgency. A goal without a timeline is a wish. Timelines are critical to success.

The big problem was (and still is, to this day) that there was no formal course or degree that I could take. Especially as training is about the most hands-on thing that there is, learning to train meant that you needed some unsuspecting souls to practice on. My being in tea planting instead of in HR (used to be called Industrial Relations in those days) didn’t help. So, I did two things. I read every book on training that I could lay my hands on and I practiced on my workers and staff. Not in formal classes because I didn’t have the opportunity to do that, but every day at work. The way that happened was that I would apply something that I had learnt, unknown to them, then I would watch for reactions, mine and theirs and record them. That was my feedback loop on what worked and what didn’t. I had (still do) a very good memory and I augmented that with taking notes as soon as I was able to. I used to carry a small notebook in my shirt pocket and would write down key words. To this day I can tell you that the pocket notebook is the fastest way to record and access any information and outperforms every gadget you can imagine.

I took every psychometric test that I could and then wrote an analysis of the report compared to my own understanding of myself. That helped me to understand psychometric testing very well. I am one of those who believe that it is a tool and not a secret weapon which enables the interviewer to look deep into the interviewee’s soul without his knowledge. All these notes resulted in a couple more books. Notes are an amazingly powerful aid to self-development. They enable you to reflect objectively on what had happened and see what options you had at the time, which you used or didn’t and decide how to behave in the future. Reflection needs a cool head, free from the pressure of emotions that is usual in the heat of the moment. For most of us, after the incident, we forget details and so when we have time to think about it all, we don’t have data. Keeping notes helps to recall the data so that our conceptual take on what happened and what to do later, is much sounder and more accurate.

Another thing I did was to enroll in ISABS’s Professional Development Program, which is a four-year distance learning program in Applied Behavioral Science, in which you learn how to facilitate group learning, while learning about yourself. It is a very rigorous course and I had some of the best teachers in the course of it. Udai Pareek, Somnath Chattopadhyay, Aroon Joshi. I also learned from Pulin Garg and Gourango Chattopadhyay. Very rewarding. That culminated in me being inducted into ISABS as a Professional Member. While I was doing all this, I was in a full-time job managing a tea estate (for 7 years) and a rubber estate (for 3 years), in which I was fully accountable for business results without any allowances for my self-inflicted learning goals. For those who may not know what ‘managing a tea estate’ means; an average tea estate in the Anamallais has an area of 400 hectares (multiply by 2.47 for acres), a labor force of about 800, a tea factory, supervisors and staff totaling to about 20 and 2 or 3 Assistant Managers. Sometimes also a resident doctor for the estate hospital. All these were the responsibility of the Manager. The workers and Staff were all unionized and sometimes, highly militant. Since the estates were in Tamilnadu, and I am from Hyderabad, I needed to learn a totally new language, Tamil which I did to a level of expertise of a native speaker. I won’t go into a Manager’s daily routine because that is not in the scope of this article. But this should suffice to give you an idea that there was not a moment to spare as far as I was concerned.

The next challenge was to get hands-on experience in training. For this I will be eternally grateful to my wonderful friends who allowed me to be a fly-on-the-wall in their training sessions. However, what that meant was that I would get a letter telling me that so-and-so was going to be doing a training session from this date to that, in this city or the other. I lived, as I mentioned, in the Anamallais in Tamilnadu. The train station was in Coimbatore, which was a four-and-a-half-hour bus ride from where I lived, down the forty-hairpin bends of the Aliyar Ghat. Then the train journey, third class (a plank for a bed) to the city that I was going to. Usually those journeys meant anything from 24-36 hours or more. In that city, I would stay in the cheapest hotel that I could find, in some cases, the stuff of nightmares. The room the size of a closet, bathroom shared between several rooms and mosquitoes galore. Food off street vendors or small cafeterias and no pay. The trainer who invited me to attend his/her class was already doing me a favor. To expect him/her or their client to pay me was out of the question. I would arrive before anyone else. Sit quietly in the back of the room and take notes. Be the gofer-boy for the trainer. And at the end of the day, I would have a debrief session with the trainer where I would share my notes, ask questions, explore alternative ways of teaching or handling exercises and games or fielding questions. After the session, back to the station to retrace my steps back home. From 1983-93, I did this in all my vacation time. I negotiated an additional fifteen days leave-without-pay from my company. Those added to my annual vacation of thirty-five days, I spent in learning how to train. In that entire period, I didn’t take a single day’s vacation. All my money was spent on books or travel cost by the cheapest means, to attend training courses. The question of comfort in travel, proper food, decent hotels and so on, didn’t even arise. All that I cared about was learning, using whatever resources I had. To give you an idea of what that was, my salary in that period went from Rs. 850 – 1100 by increments to a final princely sum of Rs. 5000 per month at the end of ten years of service. This was my investment in myself. No return to show for it and no certainty that there would ever be a return.

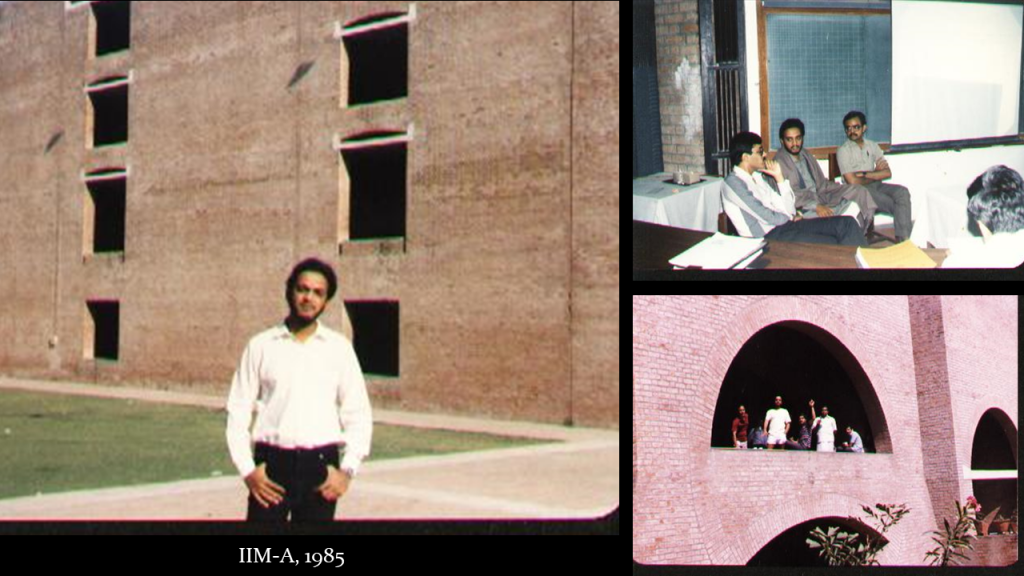

During this period, in 1985, I got married. My wife was (and is) my greatest support. What my obsession with learning meant for her was that whereas all her friends in the tea gardens had TVs and VCRs in their homes, we didn’t. Not that we had anything against movies. We had no spare cash. Every year, she would head home to her parents, and I would be off to this or that training class. Every year for ten years. In 1984, my dear friend Pratik Roy suggested that I should get an MBA. He told me, ‘Do an MBA and do it from IIMA (Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad) because it is not so much what you will learn but the name on your CV will open doors.’ I agreed. But there were two problems to overcome. The regular MBA program (PGP) was a full-time, two-year course, which I simply couldn’t afford to attend, because living for two years without a job was out of the question. So, I looked for something that would give me the same in a shorter time. IIMA fortunately had another course called the MEP which was an Executive MBA, designed for business owners and management executives with at least five-years’ experience. It was a very high-pressure course, seven-days-a-week, no holidays, in which they covered the entire two-year syllabus of the regular MBA. It was taught by the same professors, used the same case studies, but had insane hours. The only thing it didn’t have was the project which was substituted by the work-experience requirement.

Professors Labdhi Bhandari taught us Marketing; Pulin Garg and Indira Pareek, OB; Viswanathan Raghunathan, Finance; Bala (Balasubramaniam), Business Strategy. And others, equally good; each of them a privilege to study under. We had the best and their teaching, lives on in our minds and work.

The MEP is perhaps one of the best courses of its type because it gives you everything that an MBA gives you in a much shorter time. The high-pressure environment meant that only those who were serious stuck with it which was also for the good. It is very exhilarating to study with other obsessive-compulsives. We would study sixteen to eighteen hours a day, every day. We would drink tea and eat Maggi noodles from a street vendor at the gate of the Institute. He ran an all-night operation as he had a dedicated clientele in us. That high-octane tea kept us awake and we argued cases, analyzed our assessments and shot each other’s arguments to pieces; all adding to our learning. We would have surprise tests in class and the dreaded CPs (Class Presentations) where our group would make a presentation on the case that the whole class was studying which the rest of the class took great pleasure in taking apart. If you came out alive after a CP, believe me, it means you had something worthwhile to show. Living to see the light of day after all those brainy types had had a go at you, left you feeling really elated. Didn’t happen often but it did sometimes.

My second problem was money. The course cost Rs. 30,000. My salary was Rs. 850 per month. My savings were zero. I was going to get married and had saved up a little bit for that – I paid for my own marriage – so couldn’t spend it on anything else. I was in a fix. But as the saying is, ‘Where there is a will etc….’ I applied to my company for a loan to attend this course. I told them that I would be better qualified to serve them after the course and that I hoped that they would support my effort to educate myself. Apparently, they were partially convinced, so they replied to say that they would loan me half the amount, and that I would have to sign a bond to work for the company for three years after returning from the course. Also, that they would deduct my annual vacation of thirty-five days from the duration of my absence and treat the rest of it as leave without pay. So, in effect, that was added to my cost and I was still 50% short for the fees. To raise that I sold my car. I had a Hindustan Ambassador (Indianized Morris Oxford), the workhorse of India and one of two cars on Indian roads at the time, the other one being Premier Padmini (Indianized Fiat). That was a big blow because I had no idea when I would be able to afford another car. But the fee was paid, and I was accepted for the course. The course started in April 1985, but I had another matter to settle before that; my marriage. I was the Site Manager for Mayura Factory construction in the Anamallais. Mayura was to be the largest tea factory in South India and it was almost complete.

I took one week off and went to Hyderabad, got married on March 21st and returned on the sixth day with my wife, Samina. All that is another story but the long and short of it, relevant to this story is that the IIMA – Executive MBA (MEP) began in April. That was perhaps one of the toughest decisions my wife and I ever took. To separate so soon after our marriage. But we did it. Her parents were in the UK at the time, so she went off there. And I went to Ahmedabad for the course. What that meant was that even though we got one week off in the middle of the program, I would still not be able to meet my newly wedded wife, because she was in the UK. That was a strange week indeed. Everyone else left for their break. I had nowhere to go, or rather, no desire to go anywhere. So, I stayed on at the IIMA all through the week, alone. The point of all this is to show that if you want something badly enough then you need to take tough decisions. In my case, I lost pay, took a loan, sold my car, left my wife soon after we got married, all to get the Executive MBA which I considered very important. My wife supported me in this and took everything in her stride, including living a very frugal life for over a decade. After the course, we got back to Anamallais and I worked not for three years but until 1993. Eventually in 1993, I decided that I needed to take the final test of the pudding; starting up my own company.

I have talked about three things: Focus + Investment + Consistency. I did all of them. But there is a final one: Risk. Without taking risk, you can never know if what you did would really work. Risk, to a startup is like the first solo flight to a new pilot. That is when all his training shows up. There is no shortcut to this. Risk must be taken and so I started Yawar Baig & Associates in Bangalore in 1994. That sounds simpler than it was. It was simple enough to start a proprietorship company. The trick was to get business. My problem was that all my experience was as a hands-on operations man in manufacturing and large-scale agriculture and I was attempting to enter the domain of leadership training. I had no contacts in ‘Learning & Development’ or in ‘Human Resource Management’. And most of all, I had no track record of training. But I had a lot of energy and I wasn’t going to let what I didn’t have, prevent me from doing what I had set my heart on i.e. become a globally recognized leadership trainer. I hit the road. I made a list of all the MNCs (multinational companies) in Bangalore and started calling their heads. I would call the CEO or the Head of HR. I discovered that calling the CEO was a better deal than the HR Head. An operations man (there were no women CEOs at that time in Bangalore) was more likely to understand me than an HR person. Also, CEOs make decisions and don’t need to ask anyone else before deciding. There was a risk involved in that if the CEO said, ‘No’, then there was nobody else to go to. But then I reckoned that was better than going from one person to another until you got to a CEO who may still say, ‘No.’ The key was to get him to say, ‘Yes’, and not ‘No’.

I prepared my pitch, rehearsed it a million times and called. This was the Australian head of the IT operation for ANZ bank. I got his direct number from another friend who worked in that company along with the warning that he had a very short fuse. I called and he answered immediately and that’s when I discovered that there was a hole in my research; I had never heard an Australian accent before. This was 1994. I had no PC. There was no Google Search for Australian accents. In fact, there was no Google and wouldn’t be for another four years. I didn’t know any Australians and by the time I guessed what he was saying, he almost hung up. Mercifully, he said, ‘Hello! Are you there?’ I said, ‘Yes Sir. I am.’ And then I launched into my pitch (little did I know that later, I would be teaching people how to do ‘Elevator Speeches’) and asked him for an appointment. He said, ‘Will five minutes do?’ I replied, ‘Yes Sir. Thank you. See you tomorrow.’ Later I wondered if he was trying to insult me or challenge me or what the meaning of, ‘Will five minutes do?’ was. I went the next day, suit and tie, well in advance of the time. He greeted me and we started talking. He wanted training for his entry level engineers on human skills to lead IT Project Teams. After my pitch which took exactly four minutes, I said to him, ‘Thank you for your time Sir. I am finished.’ He said, ‘Na! Let’s talk about what I want you to do.’ That meeting went on for forty-five minutes

He said to me, ‘I want you to work with another consultant who is working with us’, and called in Julius Aib, who was to become one of my dearest friends and Aikido Sensei. Julius would teach the Project Management side of the course on “Project Manager Workbench” (PMW) and I would teach the human skills to lead teams. I designed a course called, ‘Critical Human Skills for Project Leadership’ and Julius and I taught it in that company for three years. Regular work is a lifeline for a startup consulting firm and that is how I got it. This course became very popular and I taught it in GE, IBM, Motorola, Wartsila (in Saudi Arabia), Andersen Corporation in the US and in many other firms.

The second meeting which stands out was with a French IT firm which had an Indian American CEO. A friend of mine got me a meeting with him. He was looking for a specific solution; and that was, how to get his direct reports to speak up in his meetings. He said to me, ‘They always agree with me. They never disagree. Then they don’t do what they agreed to do. That freaks me out.’ I realized what the issue was. He was an Indian by descent, but he was American through and through. He was born and raised in the US and had never worked in India. Now he was heading an Indian team and for his bad luck, he looked Indian. I say bad luck because if he had been white, they would have treated him differently and made allowances for his foreignness. But because he looked Indian, they treated him as an Indian, including speaking to each other in their local languages, none of which he understood. Clearly all this was hassling him and telling on the productivity of his team and on everyone’s happiness. He asked me if I had a solution.

‘Yes, I do, but I want to observe one of your meetings first before I tell you what I would like to do to solve your problem.’ He agreed. The meeting was an eyeopener and confirmed my diagnosis of what was happening. It went like this:

They were discussing an issue related to finance. The CEO described the issue (strong American accent) and then asked for the opinions of his team. They were all Vice Presidents of different functions. The first to speak was the VP Finance. As soon as he made his point, the CEO, slapped his hand on the table and said, ‘That’s a fantastic idea. Anyone else?’ There was dead silence. Nobody spoke a word. Deadpan expressions on the face, avoiding any direct eye contact with the CEO. He asked for other ideas a couple of times more; his face started to get red and he looked like he would rise like a ballistic missile and disappear through the ceiling. I decided to intervene and said, ‘Why don’t we take a break and have some coffee?’ Everyone started breathing again and stood up. The CEO realized that this was a deliberate tactic on my part and cooperated and said, ‘That is a good idea. Let’s take a break.’ As we left the room, I took him aside into an empty office. As soon as the door shut, he burst out, ‘See what I told you? This is what they do all the time. They clam up. Nobody gives any ideas. And these are all VPs and supposed to be bright people.’

I said to him, ‘Did you realize what happened there? What you did?’

He looked injured and angry, ‘What did I do? I only appreciated the man. What’s wrong with that? In America they would have come up with a hundred ideas after that affirmation.’

‘You are right, but this is not America and they are not American. This is India and in our culture the cost of ‘failure’ is very high. Nobody wants to be wrong. And definitely not in public. When you slapped your hand on the table and said, ‘Fantastic idea’, that set the standard. ‘Fantastic’ in our culture is the ultimate. It is not a simple word as in the American culture. In India, fantastic means, FANTASTIC. And when you say that with a slap of your palm on the table, it is sealed. You are in effect saying to them, ‘Here is the best possible idea that there can be. I challenge you to come up with a better one.’ Nobody then wants to take the risk to say something only to possibly have it discarded. Losing face is a very big thing in our culture.’

He listened in silence. Then he asked me, ‘What do you want to do about this?’

‘I will design a workshop on cross-cultural communication, and we will do it as an offsite for two days for your team.’

‘What will it cost?’

‘5000 per day plus my costs.’

‘How do I know it will work?’

‘You don’t. So, let me suggest a deal. How about you pay me only if it works. But if it works, then not only will you pay me, but I want you to call your friends and tell them about it and ask them to give me appointments to meet them.’

He looked at me with a quizzical look in his eye and said, ‘I like your spirit. It’s a deal.’

As they say, the rest is history. He was true to his word. Not only did he pay me, but he called other CEOs and I got appointments with almost every CEO there was. After all I had one of their own rooting for me.

You can read all this and more in my book, ‘An Entrepreneur’s Diary’.

Excitement is danger that anticipates a happy ending. That is the joy of risk taking, without which there can be no success.

Focus + Investment + Consistency and Risk (FIKR)….that is the bottom line. To continue to do that, not once, not twice, but all your life. That is what entrepreneurship is all about.