On October 20, 2010, I was 55. I published a book on that day called: 20-10-2010-55 – 55 life lessons. It is on Amazon. Those who would like to know more about me and my life should read, ‘From India to the Indies’, and ‘In a Teacup’. Both are on Amazon.

I turned fifty-five on October, 20, 2010. That’s the title of this book and blog; 20.10.2010-55. In the book, I reflected on the lessons that I had learnt in an unusually rich, active, exciting life lived in India, Guyana, America, Saudi Arabia, and in travels in other parts of the world. I wrote this book as a tribute of thanks to all those who added value to me, taught me formally and informally, and invested in my learning. During my childhood and teens in India through the 60’s and 70’s, I spent all my vacations walking in the jungles of the Sahyadri mountains in Adilabad District in Telangana, living with my dear friend Uncle Rama. Imagine the excitement of a fifteen-year-old with a .22 rifle or a twelve-bore shotgun, walking with one Gond companion, Shivayya, all over the jungle bordering the Kadam River.

At times Shivayya and I would walk in the night to witness a Sambar mud bath and sit behind a tree, quietly watching majestic Sambar stags roll in mud and then stand up to shake off the excess; coated in an armor of mud which, when dry, protects them from biting insects. Sometimes we would hear the call of the tiger as it set out for work. I learnt to read tracks which tell the story of all those who passed that way. I learnt the meaning of smells which tell their own stories and can mean the difference between life and death. But the biggest lesson I learnt was to take life seriously while having fun and to extract every drop of learning.

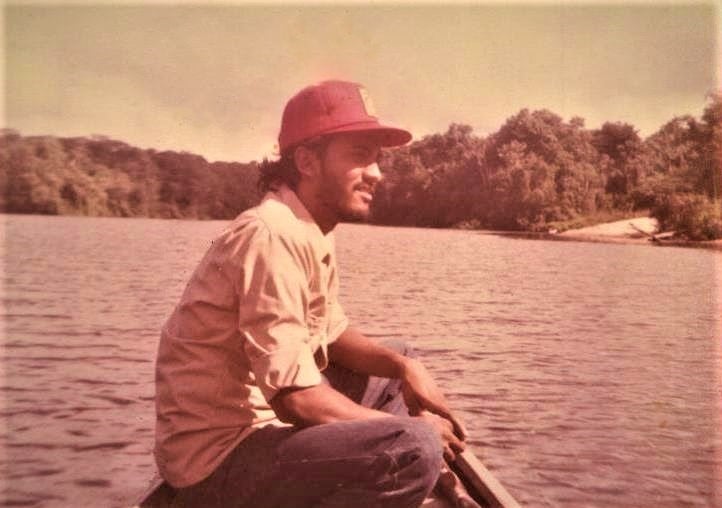

In the late 70’s and early 80’s, I spent five years in the Amazonian rain forests of Guyana bordering the Rio Berbice. I went there when I was nineteen and lived alone in Kwakwani. During weekends, my friend Peter Ramsingh and I would take our boat on a trip fifty to sixty miles upriver and camp on the bank or on a sandbank. It was our code of honor to not take any food on these trips and live off the land from our hunting and fishing. As an emergency fall back, we would take some raw chicken guts in a plastic bag. If we didn’t manage to catch any Lukanani or to shoot any Agouti or Canje Pheasant, we would trawl the chicken guts in the Berbice and sure enough, we would get a bite – Piranha. Great eating as long as you know how to keep clear of the teeth and retrieve your hook. I would see alligator eyes shining like diamonds sprinkled on the dark waters during our night patrols to check our fishing nets. During one trip, Peter and I accidentally caught a twenty-two-foot Anaconda in our fishing net. It was so heavy that both of us couldn’t lift him clear off the ground. I met people who live thirty to forty miles up the Berbice River in houses on stilts, in small forest clearings where they grow a few vegetables, hunt and fish for their meat, and don’t come to ‘town’ for months at a time; no water except the river, no light except the sun. Sometimes it is a single family of Amerindians. Sometimes it is a couple of families who live by one another. Their children play in the forest and swim naked in the river, yet I never heard of a case of Piranha bite; never figured out that one as the river is infested with Piranha and they love to bite. These families always grow the best honey which they would sell to people like me who turned up on their doorstep, or take to town and exchange for a couple of bottles of country liquor – deadly stuff in more ways than one.

I spent ten years in the 80’s and 90’s in the rain forests of the Western Ghats in Anamallais, India and further south, planting tea, coffee, cardamom, and rubber. I spent many hours tramping up and down hills and valleys, sometimes at a height of eight to nine thousand feet on the famous Grass Hills; at other times, wending my way in sweltering heat through the thick forest on the Ghats where the sun almost never reaches the earth. One day, I escaped an angry, charging bull elephant by what could only be a miraculous divine intervention. All my tea garden workers believed that I was divinely blessed from this day on; a belief that I did nothing to dispel – who would object to being divinely blessed? On another instance, I walked up to a Red Dhole (wild dog) kill – they moved away and sat in a circle watching me, while I ensured that the Sambar hind that they had brought down was dead. On a forest road in the Anamallais, I once had a face-off with a huge Gaur bull who eventually decided he didn’t hate me enough to eliminate me and moved away, allowing me to move on, on my Royal Enfield motorcycle. My greatest joy was to camp on a huge rock outcrop called Manja Parai in Lower Sheikalmudi Estate where I was the big boss, sitting on a platform in a tree to watch elephants come to drink in a nearby stream. When the elephants left, the Gaur would come. Finally, when everyone had gone their way, my companion Raman and I would descend and light a fire against the bitter cold, smoke a couple of beedis, and drink hot, sweet tea and wait for the sun to rise. Gradually, the sky would lighten; the orange glow would show and then the majestic ball of fire would come up over the edge of the horizon, greeting us across an expanse of forest and tea gardens. What is the value of such a sight?

Over the course of fifty-five years, of which thirty-eight have been working years, I have met thousands of people across races, nationalities, colors, political landscapes, genders, sizes, and shapes – ranging from business and political leaders walking the corridors of power (in 2008 I met the King of Saudi Arabia, His Majesty King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz ibn Saud at a banquet in his palace in Mina; the Prime Minister of Guyana, His Excellency Mr. Samuel Hinds is a personal friend of thirty-five years standing), to religious scholars (Muslim, Christian, Jews, and Hindu), union leaders, anxious parents of children who have become strangers to them, heads of family business – billionaires who would give half their kingdom for peace of mind and real happiness, poor farmers and hunter gatherer tribesmen and women who have little, but are ever happy to share it with you. They have problems like the rest of us, maybe even more, but you don’t see that on their face or hear it in their voice.

I met tribal leaders in their villages, one of them comprised of four huts in the rain forest in the Western Ghats in India and broke bread with them and to their utter astonishment, played with their children. I drank milk straight from the udder of a buffalo and honey straight from the hive, with the blessings of the owners. I swam in forest rivers that have no names, rode horseback on the English Moors and fished for Piranha and Arapaima in Rio Berbice. I have driven cars, SUVs before the term was invented (we called all of them ‘Jeep’), Caterpillar dump trucks, bulldozers, and boats. I rode a buffalo into a lake until it decided to dive and I floated away. Mercifully, I grabbed her tail and she towed me back to shore. I met teachers, parents, and students in South Africa, Malaysia, India, Guyana, U.K, and America and wondered at our similarities which far overshadow our differences. I have spoken to audiences ranging from a few people in a room to nine-thousand people in the great masjid of the International Islamic University in Malaysia and marveled at how easy it is to connect to people across every imaginable boundary. I was one of three million in Haj on more than one occasion and if I had a dollar for every smile I got from a stranger, I would be a rich man. I feel I am a rich man anyway because of all the experiences that life has afforded me.

I have been in life threatening situations more than once, facing direct personal danger sometimes from both, two legged and four legged creatures, but I am still here. I studied many religions and philosophies and then came to Islam with my eyes wide open. Though I was born in a Muslim home, my Islam is by choice, not chance. Having seen both the rich living responsibly or irresponsibly, and the poor living with self-respect and dignity or justifying all sorts of bad actions by reference to poverty – I have developed a strong sense of justice and compassion. I believe the two must go hand in hand.

I also learned what I consider to be the two most important lessons in my life, after sharing which I will end this introduction.

The first relates to the fact that essentially we are all in control of our lives and selves and no matter how powerful or powerless we may believe we are, there is always something that we can do to make a difference.

‘I will not allow what is not in my control, to prevent me from doing what is in my control.’

The second relates to the fact that everything we do counts and defines us as human beings and becomes our legacy to the world. I ask for the courage to do what is in my control, fearing nobody but my Creator to Whom is my return.

‘All that we chose to do or chose not to do, defines brand value and character.’