It was 1983. At this time, I was still in the plantations, had no money, and even less time. I was in a job that started at 6:00 AM and ended at 6:00 PM except that I was supposed to be on call twenty-four hours, seven days a week. This was before we’d heard the term 24 x 7, but we worked twenty-four-seven. As for the money, I started in 1982 at a salary of Rs. 900 per month which went to the grand total of Rs. 1100 the next year because I did so well that I was given a special increment. To put this in perspective, the Rupee to Dollar conversion rate at the time was approximately 10 rupees for every dollar, which meant I made $90 per month in 1982 and $110 the following year. Money lasted longer in those days. I remember the feeling of enormous wealth one day when coming out of the State Bank of India in Valparai, I looked at my updated passbook and found all of Rs. 500 ($50) in my account. Be that as it may, Rs. 1100 was still not bags of gold and so traveling to learn meant that traveling for any other reason was not possible.

It is only when resources are strained that you use your brain. I saved as much as I could and then negotiated a deal with my company where I would be given 2 weeks per year of unpaid leave and be free to earn what I could by way of fees. In the initial year or two this meant nothing because not only could I not earn anything but, on the contrary, had to spend my own money and time to learn how to train by working as an apprentice under various kind souls who allowed me into their classes. But in India in those days, if you traveled 3rd class and stayed in dingy hotels and ate little, money went a long way. And so, I learned. I would sit quietly in the back of the class and be the ‘go-for’ boy for the main trainer. I would clean the blackboard and get water for the trainer or take his or her notes while they spoke to the class. These were the days in India of blackboards and flip charts. Nobody had heard of whiteboards and markers and whatever sat on your lap could not be typed upon. LCD was something that came in cheap Japanese watches and projectors were things in cinema halls. The TV was something that most people (including myself) had not seen and certainly did not have in their homes. And the internet? Well, who is that??

At the time, people weren’t talking about leadership training in India. Indeed, training was not a very remunerative activity at all. What little was done was done internally and was almost entirely technical training in how to work some machine or the other. When you spoke to people about training and development, they looked at you as if you were some sort of spaced out sky-rider. People didn’t take such things seriously. People looked at the word ‘leader’ with suspicion because to them a ‘leader’ in the company was a union leader and they certainly didn’t want those. It was quite common to go to an Indian company to speak to its CEO who would say, “What do you mean by leadership training? I don’t want leaders. I want people to do what they are told. Leaders create trouble.” It took a lot of convincing to get the CEO even to try one course free. Most training was done as a solution to a problem – low sales, low motivation, or conflict. Consequently, training was sporadic and event oriented. Developing leadership was not perceived as a need and the term was viewed with suspicion. That leadership development was the secret to greater productivity, employee satisfaction, career advancement, and employee retention was something that they never considered. Employee retention was not an issue at all. It was a buyer’s market. People had limited choices for employment and if you were lucky enough to get a job, you stayed in it until you retired or died, whichever happened first. Happiness in the job was an oxymoron, so to speak. It just didn’t matter. You did your job to feed your family, not to be happy. Even if you were not happy in it, you still stuck to it, because your family had to eat. Employers were of the view that by giving you a salary they were doing you a major favor and what you did in return for that salary was to be expected and not necessarily appreciated publicly. Many gave you a brown paper envelope quietly with your bonus money in it. Not to be mentioned to anyone else, please. Others didn’t even do that. Mine certainly didn’t. And if you didn’t like the situation, you were free to leave and seek your luck elsewhere – but there was not much elsewhere to look. It was in this environment that I decided to embark on a career to teach leadership to people who didn’t know what it was and so didn’t care to learn and to get others (their employers) who didn’t want to pay to support it. The big question for me was, ‘How does one do leadership training and how does one make it into a life supporting activity?’ My life. I wasn’t planning to live in poverty either, so it had to become remunerative and fast.

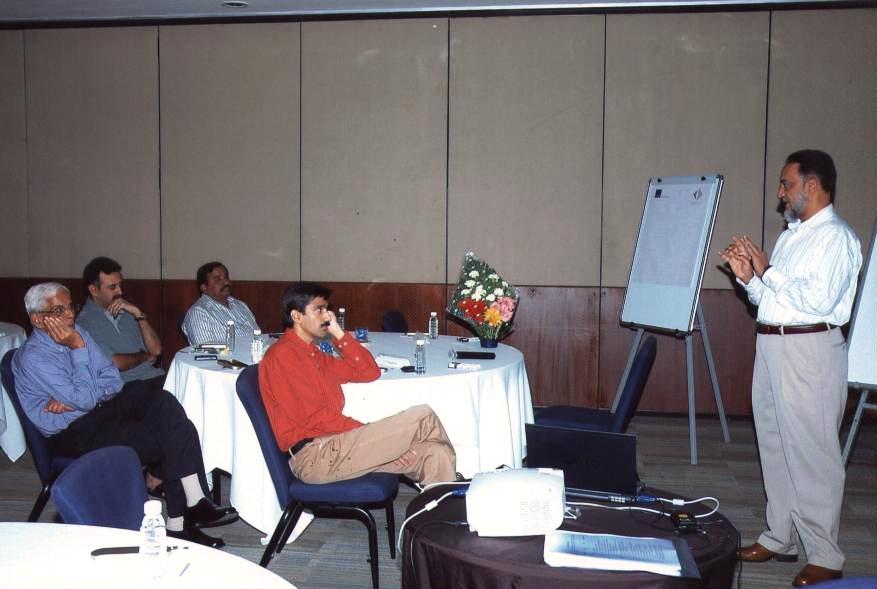

It was the large-scale entry of multi-nationals, especially in the IT sector, in the 90’s that changed this scenario and training became a regular initiative that was programmed into the year, and which was seen as ongoing learning. In twenty years, the Indian corporate world has come a long way to the situation where today the most challenging, argumentative, and sophisticated audience that you can ever hope for is an Indian audience. Not only are they likely to be the most educated, but also the most traveled, most likely to ask tough questions, and most likely to need some very solid evidence to convince them to do what you want them to do. In my own view that makes an Indian audience the most rewarding to teach. Like mountain climbing, satisfaction is directly proportional to difficulty. And that, with an Indian audience today, is almost a certainty.

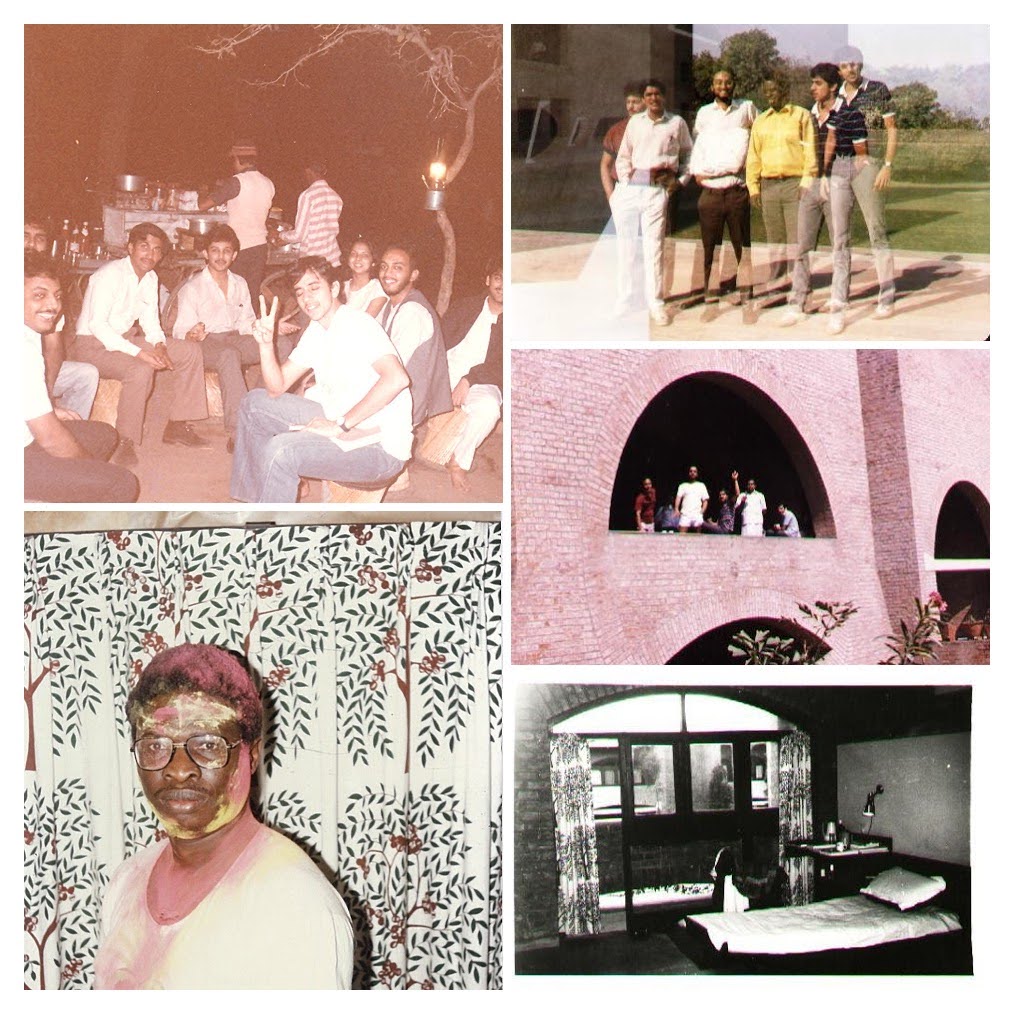

It took me another eleven years before I actually took the next step forward of making this my career, but I never had any doubt that this was what I wanted to do. From 1983-1994, I worked at gaining experience and qualifications in management consulting and leadership training. I did a mid-career executive MBA at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmadabad, the premier management school in India. I earned a doctorate level qualification in Applied Behavioral Science though since the organization awarding it was not a university it was not called a PhD. I have always been more concerned with learning and application – not with ranks, degrees, or certificates. I earned various certifications on different psychometric instruments and tools. And most importantly, I paid for all of these myself. In some cases, I persuaded the authorities to give me concessions. In other cases, I borrowed money from friends who believed in me. For my MBA, I sold my car, borrowed money from my company, and from a very dear friend. My employer gave me leave without pay, charged me an interest of 8.5% on the loan, and made me sign a three-year bond to work with them after my MBA. Such was the foresight of people at the time. Ongoing education was obviously not seen as very important and people who wanted it were in effect penalized for wanting such outlandish things. But I was clear about my goal and willing to pay the price.

Simultaneously, I informally contracted with several friends who were trainers to attend their courses as an observer. This meant traveling to whichever city they were working in, staying there on my own and being their ‘go-for kid’ for the duration. In the evenings I would sit with them and ask questions about what they did and why. I would participate in design meetings mostly by keeping my mouth shut, but listening carefully, especially to the diagnostic rationale for whatever interventions were decided. I am most grateful to those friends and senior colleagues who allowed me into their lives to learn from them. I had to pay for my travel and keep but not one of them ever charged me a single penny for teaching me. This is the reason why making money as a coach is very difficult in our culture, but I am very happy indeed that this is so and gladly encourage this culture of giving free advice today, when it is my turn to pay my dues.

If those who taught me had charged me a fee, I would never have been able to pay it. That is why I don’t charge anyone a fee if they want my advice in learning to be trainers. Having said that, I have yet to find anyone who had the determination and willingness that I did, to do whatever it takes to learn. I don’t mean to boast but to drive home the point that if you want a mentor to do his best for you, you must demonstrate to him that you are worth his while. And that means making no excuses, doing what it takes to demonstrate total commitment, and demonstrate your learning so that the mentor also feels satisfied with the teaching. For my part, I doubt if they could have found a more willing and attentive student. And they appreciated it. For a teacher the biggest motivator is a student who is serious about learning and who is willing to make the effort to help himself. I made sure that I demonstrated my eagerness to learn and treated these sessions very seriously.

Another issue was that of time as I was not only in a full-time job but the job was in the Anamallai Hills and traveling anywhere meant adding two days to the itinerary. I used to get thirty-five days annual vacation and the train fare to my hometown as a travel allowance. For eleven years I used all of it to travel to various cities to learn how to train. I used all the spare cash I had (and there wasn’t much) to buy books. The first independent assignment I got was to teach a course at the SVP National Police Academy in Hyderabad in 1991, for which I was paid Rs. 500 per day. That was a dream come true because it proved to me that I could survive on my own. Rs. 500 is not much – in 1991 it meant approximately $28 – but for me it was proof that there were people out there who were willing to pay to learn.

In 1985, I got married. That was also the year in which color TVs came into the Indian market, thanks to the Commonwealth Games. We lived in the plantations as I mentioned and there was really no entertainment other than watching movies on a VCP (video cassette player). Most of my friends bought color TVs on hire purchase and upgraded to VCRs (video cassette recorder). There would be parties to watch the latest tennis or cricket matches or to watch some favorite movie or the other. During this entire period, we did not own either a TV or a VCR. We eventually bought a TV many years later, a couple of years before I left planting. I came in for a fair amount of ribbing for not being ‘in’ with everyone, but people also appreciated my focus on learning. My wife has always been extremely supportive and made personal sacrifices. In those days it meant that we never took a holiday together and that she did not have the means of entertainment that others had.

The year I got married, 1985, my dear friend Pratik Roy gave me some advice when I spoke to him about my desire to be an independent consultant. He told me that having an MBA was essential and if I could get it from one of the top-notch colleges in India that would be best because the ‘name’ counts. At that time, I neither had the time nor the money to do a regular two-year program, so I did what turned out to be better – the MEP.

IIMA (Indian Institute of Management, Ahmadabad), the most famous and prestigious of India’s Business Schools ran an Executive MBA for people with organizational experience, called the MEP. Sensibly, they gave people credit for their hands-on experience of managing businesses and plugged in the theoretical part in a highly intensive residential program. On Pratik’s suggestion, I applied for this program and was accepted. The problem was the fees and the time off from my job. The fee was Rs. 30,000. That may not sound like much today, but in 1985 for someone who was earning just over Rs. 1000, that was two and a half years’ salary. There was no way that I could afford this fee on my own. And there was still the issue of time off.

I asked my company if they would sponsor me to this program. They refused. I tried to convince them that if I acquired this education, I would be a far more productive employee and that would benefit the company above all else. They refused to see this benefit. They said that I was productive enough as it was and if I wanted to further my education that was my personal choice, but they were not going to spend money to help me.

Then I asked them if they would give me time off without pay. They agreed. I asked if they would give me a loan for the fee. They eventually agreed to loan me the amount at 8.5% interest provided I signed a bond to work for the company for three years after I returned. And off I went to Ahmadabad, by third class train from Coimbatore. Such was the awareness about the importance of ongoing employee education in those days that not only did companies not sponsor any, but they also didn’t support employees who were willing to spend their own time and money to further their education. Mercifully, we have come a long way since then, though I was not the one to benefit from this change. At least in my company, I can say that I was the pioneer who opened the door for others who were supported by the company thereafter.

I spent the entire duration of the MEP away from my wife, less that one year after our marriage. During that entire period, she went to stay with her parents in Leeds, UK. That meant that in the days of no WhatsApp and free international calls combined with my poverty, I didn’t get to speak to my wife even once. Not only were international calls not free, they also couldn’t be made from our rooms. If I wanted to speak to my wife, I would have to go to a Post Office, get the operator to book the call, wait for it to come through which can be at any time of the day or night, then speak very loudly thanks to the usual terrible connections before all the others who would also have come to speak to their loved ones. In India everyone is very interested in everyone else’s lives and would have been delighted to listen to my conversation with my newly wedded wife and after the call would have undoubtedly given me some very valuable advice on how I should conduct my married life. However, I was not interested in either the public demonstration nor the free advice, so I never gathered the courage to make this call. Remember, I haven’t even mentioned the cost of international calls, because when you don’t intend to do it, why talk about the cost? I had no time to write letters and couldn’t make calls but we remained married and have been now for 38 years Alhamdulillah. My wife has always been my greatest support.

In the middle of this the IIMA took pity on us and gave us a one week break where everyone, and I mean everyone and his cat, went home. I couldn’t go anywhere because I could hardly go to Leeds for a week, even if I’d had the money, which I didn’t. So, I stayed put on campus. The authorities allowed me to continue to eat in the dining hall, which was free, and so I survived on a diet of tandoori chicken and Vadilal ice cream. True, there was the odd roti thrown in, but the cook knew that I liked TC and they indulged me. I would go to the gym in the morning. Then shower, eat lunch TC+VIC. Then sleep for two hours. Then tea, run around the campus, then dinner TC+VIC and hit the sack. The week passed. Learning? This too shall pass. IIMA in isolation – because even regular MBA classes were over and apart from staff and faculty who live in campus housing, there was nobody on campus – is an experience that I am not sure anyone else has experienced. All said and done, it was a very relaxing and rejuvenating experience. Something to be said for a diet of TC+VIC and lots of exercise, I guess.

My idea of describing these days in such detail is not to promote tandoori chicken, but to share my learning, that in life if you want something you must be prepared to pay for it. Sounds so simple and indeed it is. That is why I am so surprised how so few recognize this truth and work for it, while claiming to truly want success in their chosen endeavor. This price, like in cars for example, depends on the car you want to buy. You can get a Ferrari or a Rolls. But not for the price of a Hindustan Ambassador or a Hyundai. We understand this about life. But not about life. Same difference. You want something, pay the price. Pay your dues and you will get it. There are no shortcuts. Look at the life of anyone at all who you consider to have been successful and you are looking at a man or woman who paid their dues. So, if you truly want success, ask yourself if you are willing to pay the price. It is really an investment in yourself. Are you interested in making it?

The lessons I learnt in this entire difficult incident were that when someone says they won’t do something it is not necessarily final. Some people test you by denying your request to see if you are persistent enough to succeed. Others deny you because they are afraid of what doors they may be opening by granting your request. Others deny you because they can’t see how they stand to benefit by agreeing. In all cases, the onus of proof is on you. And that is fair because it is after all your need. Many times, people want to help you but need an acceptable way to do it. It is up to you to understand their world well enough to show them a way that will work for them. They are afraid to do it up front as they fear it may create difficulties for them later. In my case, I believe my bosses were afraid that others would ask to be sent to various courses which they were afraid they could not afford and so the ‘best way’ was to refuse me. They gave me a loan because they could give that to anyone and knew that in any case nobody else was focused enough on learning to ask for a loan and leave without pay to go and study. For me this underlined the point that one must not give up trying because one way fails.

The second lesson was that just because one door closes it does not mean that you can’t achieve something. It just means that you can’t achieve it in that way. There may be many other ways to reach the same goal. I could not get sponsorship or leave. So, I asked for leave without pay and a loan. The third lesson was that if you want something badly enough then you must be prepared to pay for it. And if you pay for it, you will get it. If you want it badly enough then the price will be worth it and you will be happy to have paid it, as was in my case.

Although I can’t say that my education directly got me promotions, my attitude of being focused on self-development, reading, writing, and teaching earned me a lot of respect among my peers and superiors. It was due to this focus combined with producing superior results that I had the fastest career growth of anyone in that company. Interestingly, after I returned and they saw the results of my education my company sponsored two other colleagues of mine, all expenses paid for the same course. Unfortunately, nobody offered to reimburse my expenses and I was too proud to ask. I, however, don’t regret it one bit because that education helped me, and I have capitalized on it many times over. It was well worth the money.

It underlines for me the reality that if one wants to develop himself then one must make the effort and spend the time, money, and energy himself. Our career is truly in our own hands. The sooner you realize that and invest in it, the bigger your advantage. The reality is that for every one person who is development focused there are ten who are not. Start early. If one has the support of the environment, then that is a bonus. But to link your education to what any organization can or will provide is to ensure that you don’t get any education worth the name. Today, organizations are conscious of the value of education and are supportive and take the trouble to train people, but not everything you need to know to succeed can be taught in a two-day corporate course. The maxim about investing in one’s own learning holds good. Some people today seem to equate education with corporate training. The two are poles apart. Corporate courses at best sensitize you to the need to learn and teach you a few skills. You still need to read, experience, write, reflect, and conceptualize to acquire any learning worth the name. It is good not to confuse one with the other.

The MEP was an excellent idea because it was a highly intensive course with more than sixteen hours of study per day, every day of the week. We would have group discussions on case studies until the early hours of the morning on most days and then had to be in class at 9 AM the next morning. Some of these discussions would end up at the Maggi Noodles & Tea Stall at the gate of IIMA. I don’t know if that guy is still there, but he was a classic example of an entrepreneur taking advantage of a market. Where else in the world would you be able to get hot noodles and tea at 2 AM? He saw that students needed something to eat at that hour, were willing to pay for it, and so there he was. We would sit on rocks by the roadside, and he would be there behind his stove mounted on a trolley, cheerfully dishing out noodles and tea, and if we were in the mood for conversation, then enlightening us with his opinion on everything under the moon. In India we see such small entrepreneurs everywhere, capitalizing on a need that may be restricted to a local area, but which is sufficient for them to make a living. As a result, we have all kinds of services at unimaginably low prices, the result of competition. All thanks to the individual entrepreneur identifying a need and making a living by filling that need.

Maybe even ironic to reflect that a real live entrepreneur was making money feeding would-be entrepreneurs who were focused on getting a degree. Testimony to our blindness, not one of us ever spoke to that man about doing business. To any IIMA grads who read this: Did or do any of you speak to him even today? That is assuming that he is still there. The finest examples of entrepreneurship are on the street, not in the hallowed halls of fancy colleges.

Yawar! That’s a great informative article and reminded me so much of our days in the Anamallais!!! We used to live and work across the Sholiyar Valley… It was nice to read your experiences. Our regards to you and Samina.