“So, Comrade Baig, you have been living here for two years. What are your impressions about our country?” The interviewer was from Guyana Chronicle, the main English newspaper. I was being interviewed because I was there. Comrade was a gender-neutral term used to address anyone because Guyana was a socialist (communist) country ruled by an ironman with an iron fist, not always in a velvet glove. My interviewer had come in preparation for a great event, the visit of the President, Hon. Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham who was the leader of Guyana from 1964 until his death, as the first Prime Minister from 1964 to 1980 and as second President from 1980 to 1985. I lived in Guyana from 1979-83 and so in the middle of the reign of the President Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham. We called him Comrade Burnham; meaning we referred to him as that. When he visited Kwakwani, he arrived by helicopter, which was a grand spectacle in itself and for many Kwakwani people, including myself, it was the first time any of us had seen a helicopter. The helipad on Staff Hill was surrounded by people all waving PNC flags and screaming their welcome above the roar of the rotors. As the helicopter landed, the dust thrown up effectively shut everyone’s mouths. Since he was the guest of our company, Guymine, Berbice Operations and I was the Assistant Administrative Manager, it meant that I got to stand to one side with the senior managers including the CEO who welcomed Cdr. Burnham. There was Haslyn Parris, the CEO of Guyana Mining Enterprise (Guymine), Stephen Ng Qui Sang, the Berbice Operations Coordinator, Walter Melville, Personnel Coordinator, James Nicholas Adams, Berbice Operations Administrative Manager and my boss and George Schultz, Berbice Operations Mines Manager. All of them were in the front line welcoming the President.

Among the things that were peculiar to the reign of Forbes Burnham, (I use the term because to all intents and purposes he was a ‘Ruler’ more than a leader. Some called him ‘Dictator’) was his no-nonsense style, which translated into no tolerance for any opposition to his policies. Guyana of those days had a pall of fear over it and if you knew what was good for you, you didn’t talk politics. I knew what was good for me. Burnham was dealing with the aftermath of freedom and he and his party chose the socialist way. Guyana was called the Co-Operative Republic of Guyana and was closely aligned with Cuba and Soviet Russia, though it was officially part of the NAM (non-Aligned Movement). This was not to the liking of either the Americans or the British, Guyana’s erstwhile colonizers but that was reality. Guyana paid a high price in facing political blockages resulting in shortages at home. However, by today’s terms, things were still easy. Unlike today, Guyana had not discovered that it had oil and so nobody was particularly interested in what Guyana did or didn’t do. There was bauxite and sugar. There was some gold, but it was not really extracted in any big way. There were and are major rivers but no hydro power. There was no organized or large-scale agriculture except sugarcane. Nor was there ranching though there was land enough and more for both. Guyana was poor despite being resource rich. What was also happening was the reality about payback time after any revolution. People who struggled for the freedom remember the promises made during the struggle and are looking to live happily ever after, forgetting that that is only a last line in fairy tales. To develop we need education and very hard work and neither is quick.

Burnham’s policies drove Guyanese out of Guyana and many migrated to the United States, Canada and the UK. It used to be said at one time, ‘There are more Guyanese in Brooklyn than there are in Guyana.’ True or false, there were too few in Guyana and those that remained were people who really couldn’t leave or were in government jobs where political affiliation counted for more than any competence. The results on the economy and society were hardly surprising or beneficial. On that day Comrade Burnham ascended the podium that had been constructed and spoke, short and clear. I still remember this line in his speech. He said, “A-we Gainese wan far go-va-men to give us everytin while we sit upon we sit-upons and wait. Lemme tell ayo dat if ayo wan devlopmen, ayo gon hav to wok fo it. But we like to sit upon our sit-upons and talk about what the Go-va-men mos do an vat Mistah Bonham mos do but nevah about wa I mos do. That won’t work. Unless we decide to get up and help ourselves, nothing will change.’ To me, that made perfect sense. And if someone didn’t like the man because he spoke plainly, well, that is their choice. Burnham was also known for and liked or hated for some of his policies, among which was the banning of wheat flour and the promotion of rice flour. Guyana grows rice while wheat was imported. Naturally this went against the established food habits of people and they didn’t like it. Burnham did it to reduce the import bill, but economic policy succeeds or fails more for subjective emotional reasons than objective logical ones.

Burnham decreed a policy of self-reliance and many imports including food staples were banned. Among the things that were banned apart from wheat flour were also Irish Potatoes, which was rather ironic seeing that potatoes are actually South American and were imported into Ireland. The result was that one night someone came to my house and rang the bell and looking over his shoulder, presented me with ‘forbidden fruit’, three Irish potatoes, smuggled in from Suriname, no less. For an Indian, getting three potatoes as a gift was strange to say the least, but since I lived in Guyana and was totally acculturated, I knew what a great honor and sign of friendship that gesture represented. Forbes Burnham was feared and respected, loved and hated. All hallmarks of strong leaders.

Kwakwani Park Labor Club was an institution. This was a place which had a large hall which doubled as a cinema with a stage at one end. It had a long veranda along one end on which were placed tables at short intervals where people played dominoes with great passion and noise. Inside was the bar, the place for many a meeting, fight and romance. The level of noise in it can only be experienced, not described. The Club could be heard before it was seen. And its smell was never to be forgotten. Playing dominoes in the Kwakwani Club seemed to consist of smashing the domino on the table with all your might and shouting at the top of your voice. I can vouch for the fact that going by this criterion the people who played dominoes in Kwakwani Club must have been world champions. If the game is more than this, then I must beg forgiveness for my ignorance. The Club was also remarkable for its smell. Imagine a combination of stale sweat, beer, and rum floating on heavy humid air in an invisible cloud that came at you as soon as you were within reach. Then it clung to you and entered every exposed pore and remained with you and your clothes through several baths and washes. But this did not seem to bother anyone to the best of my knowledge.

The people of Kwakwani were mostly of African descent. This, however, is a generalization because in Guyana the racial mixture is so rich that most people seem to be a combination of many different races – Amerindian, Chinese, Indian, African, and European. Demographically, Guyana had at that time about sixty percent people of Indian descent who mostly lived on the coast. They used to work on the sugar plantations, having been brought in by the British as indentured labor from India. Another main occupation of theirs was small time trade. Twenty percent of African descent who were the descendants of African slaves and also worked on the sugar plantations. When the emancipation of slaves happened, they walked off the plantations and settled in the hinterland, engaged in timber extraction and whatever else they could do. The timber and mining industries are dominated by them, as are also the Army and the Police. The last twenty percent consists of the indigenous Amerindian tribes, originally hunter, gatherers who have been exploited mercilessly by everyone else. They still live in the forests, though many now live and work on the fringes of whichever town or village that happens to be nearby. They have the least paying jobs and live mostly by selling wild meat, fish, honey, balata (wild rubber), and sometimes by working as guides for others.

In this final section of the population are also the descendants of the Chinese laborers who were brought by the British to work on the railway, most of which has fallen into disuse and is rotting away. Guyana had become independent less than 10 years before I got there. So, ideology, in this case communist, was still very strong. As I mentioned earlier, people called each other ‘Comrade,’ which depending on the tone of voice could be given any kind of connotation from the most warmly cordial to the positively hostile. As in many such cases, not everyone was a ‘believer,’ but to appear to believe was required. Since ideological alignment was more important than everything else, efficiency suffered and people who claimed to be loyalists of the ruling party, the PNC, had personal power far in excess of their official position.

On Sundays a film would be screened in the Club. Most of the spectators apparently believed that they could influence the outcome of whatever was happening on the screen if they shouted at the actors. So, they proceeded to do the same with great gusto. But strangely nothing seemed to change. The actors continued to do whatever they had intended to do in the first place. Much like government policy in our so-called democracies, which seems to be independent of the screaming and shouting of their poor enslaved populations who have not realized the fact that the script has been written by someone else and will not change with their screaming. Little did I realize while attempting to watch a film in Kwakwani, that I would live to see a real-life version of this behavior, thirty years later.

About a kilometer away from Kwakwani Park, up a small hill was the Officers colony called Staff Hill. In typical British colonial style, the rulers were separated from the ruled. Even ten years after independence, Staff Hill was informally out of bounds for ordinary people. It was meant for Officers, in this case, all black West Indian or East Indian (people of Indian origin) and though we no longer had a fence and guards as used to be there in the past, nobody from Kwakwani Park actually came up the hill except to bring some visiting relative for a short drive to show them how the other half lived. White and black is not about color; it’s about social status and attitude.

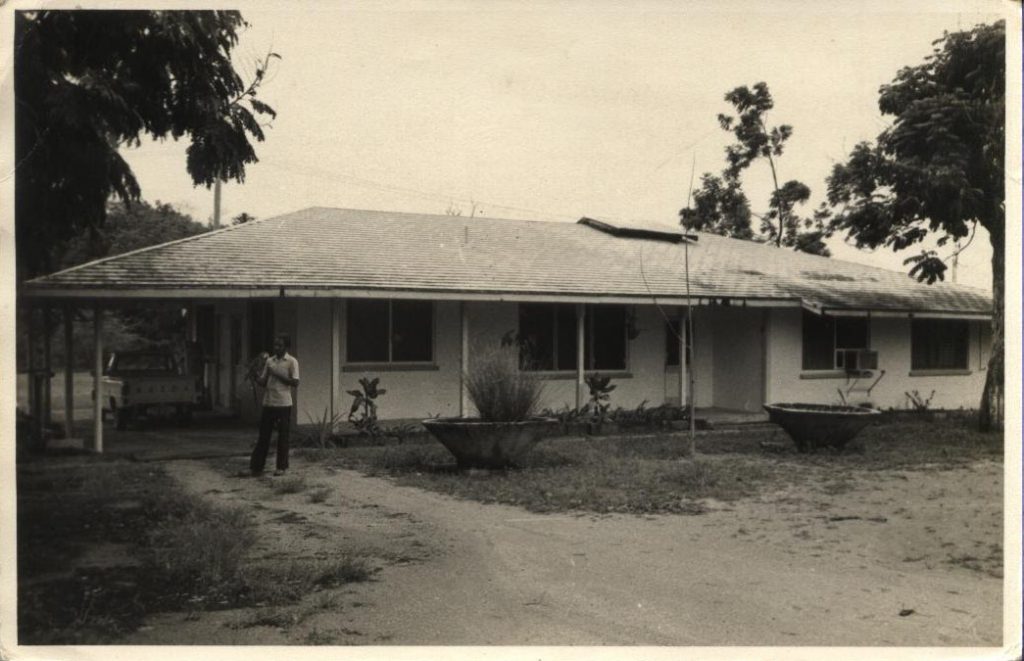

Staff Hill had two kinds of houses. Bungalow type houses with 3 bedrooms and a veranda all around them for most of us. And big wooden houses on stilts with parking underneath them for the really big bosses. The houses were arranged around a quadrangle with an orange orchard all around them. There was a swimming pool to cool off. There were tennis courts, a Club House with a bar, guest rooms, dining room (excellent cooks to boot) with proper dinner service, uniformed waiters, table tennis table, and a library.

The rules of this Club were very different. The barman wore a uniform and gloves. You could not play dominoes here. And you could not come to the Club in your shorts and nothing else. You could not shout at the top of your voice and you could not curse. And no matter that the British were long gone – as in the case of India, their ways had been adopted by their erstwhile slaves and upheld as a sign of their own ‘superiority’ over their own brethren. I am not saying that there is something intrinsically good about cursing and yelling and unwashed shirts. I am merely pointing at the reasons we do some things and how we use certain norms to demonstrate our own superiority over others.

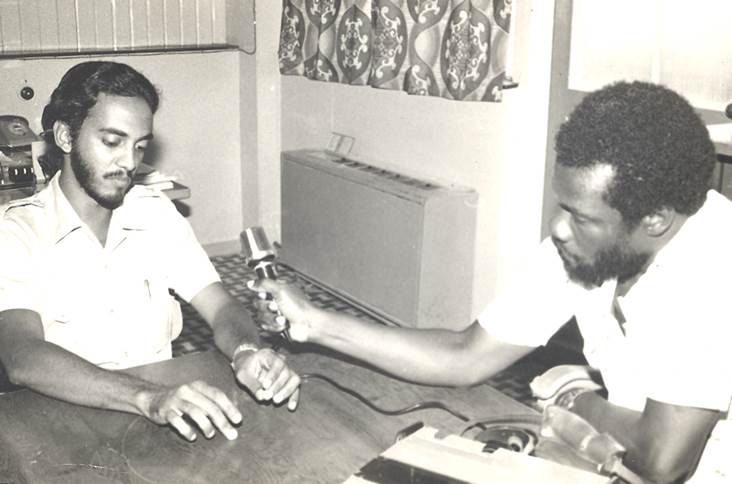

In Kwakwani Park was the hospital where for a year my father was the resident doctor, Nurse Liverpool the Head Nurse, and MacFarlane the Compounder. All wonderful people who ran a very good hospital indeed. Kwakwani was a lovely small town where you knew everyone, and everyone knew you. There were no strangers in Kwakwani. Everyone knew what was happening in your life and had an interest in it. And you in theirs. People had the time to stop whatever they were doing to chat with you when you came past. Nobody passed anyone on the street without saying, “Aye! Aye! Maan!! Ow ya doo’in!!” Remember to end on a high note as you say that, to know how it sounded.

They may add, “Ow de Ol Maan?” (Could mean your father or your husband, depending on who you were). “Ow de Ol Lady?” (wife or mother). “Ow de Picknee?” (Believe it or not, that means children). And remember that had nothing to do with whether you were married or not, as I learned to my own embarrassment one day when I went to the Income Tax office to file my tax return. The lady at the counter offered to help me fill out the form, which I gladly agreed to have her do. She asked me at the appropriate column, “Married?” I said, “No.” She then asked, “Any children?” I said, “I already told you I am not married.” She looked up at me and said, “Wad de hell dat ga fa do wid anytin Maan!!” To end this line of discussion, I immediately accepted defeat and said, “No children.”

The language of the Guyanese is called Creolese. It is an English Patois and as distinct with its own flavor as French Patois is from French. Creolese has the taste of Cookup, the sound of the Steel Band. and the aroma of the rain forest. It is a language of the people and reflects their culture. I used to speak it so fluently that new locals I met wouldn’t believe that I was not a native.

They would ask me, ‘Weya fraam?’

‘I’m Indian.’

‘Me-no-da bai, A-mean weya from in Giyana?’

‘Me-na from Giyana, me from India.’

‘Ah! (That is said as an exclamation in a high rising tone) – Ya tak jus laka-we’

And that was a great compliment. It is really impossible to render Creolese into text because it is spoken with so much emotion and voice modulation that without those sounds, it’s not done justice. It is a language that comes straight from the heart. Creolese has many proverbs and funny stories with morals that are typical of the language and the people.

For example, there is a famous proverb: Han wash han mak han com clean (When two people help one another, they help themselves).

Another one: He taak caz he ga mouth (He talks nonsense). A very important political skill, I would add.

As for stories, there are several. And in them, the people of color may appear lazy, but are smart and the White man is the butt of the joke. Here’s one:

One day a black man (Blak-maan) be ga-in about lookin for sometin ta eat when he com upon dis garden in de bush. Dey he saw dis great big bunch of ripe bananas. De man! He very appy! He put he arms around the bunch of bananas an sey, ‘De Lord is my shepherd and I shall not want.’ He hear a voice saying, ‘If you don tak ya hands off dem bananas, I gon lay ya down in green pastures.’

Dey bin the owner of the garden watchin over he garden when dis man go dey.

And knowing the Guyanese, once this happened, I am sure the owner would have given some bananas to the hungry man to eat. I don’t know of any Guyanese who would chase a hungry man away. Guyanese have big hearts.

Another one involves an Amerindian guide and his white employer. They are walking through the rain forest. The Vyte-maan (White man) sees that the Amerindian is walking barefoot, carrying his boots on a string over his shoulder. So he laughs at him and says, ‘You ignorant Amerindians are so stupid. Why are you carrying your boots?’

The Buck-maan (Amerindian), he na say nothn.

Then they come to a stream. The Vyte-maan tak off he shoe and the Bok-maan, he put on he shoe.

The Vyte-maan laugh at he again and seh, ‘This is really stupid. Now that we have to wade through the water you put on your shoes? The shoes will get spoilt.’

The Buck-man, he na say nothn.

As they wade through the stream the Vyte-maan get hit by a stingray. He scream in pain and fall down. The Buck-maan drag he out onto the other bank and seh, ‘Now who stupid? When me eye cyan see, me na need no shoe. But when me eye cyant see, is weh I need de shoe maan. So, who stupid, me ah you?’

Another brilliant one is about this Blak-maan who goes looking for work. In Guyana, the custom is that the employer feeds the worker. If the worker works for the full day then the employer gives him a lunch break and lunch. So, this Blak-maan comes to the mansion of a Vyte-maan. The Vyte-maan says to him, ‘I have a big tree in the back garden that fell last night. I want you to saw it. But you guys are lazy. You take too long to eat lunch. So, what I’m going to do is to give you food now. You eat first then you work through till the evening without a lunch break.’

The Blak-maan agrees. The Vyte-maan gives him banana and cassava and mutton and tea and the Black-maan, he eat like it is his last meal. When he done, the Vyte-maan tell he, ‘Come over to the back and I will show you the tree you have to saw.’ The Blak-maan goes around the house and there is this huge tree that has fallen. The Vyte-maan say to he, ‘Alright, you see that tree over there, you have to saw it.’

The Blak-maan he look carefully and seh, ‘Me na see no tree.’

The Vyte-maan can’t believe his ears. ‘What do you mean you can’t see the tree? It is that great big tree lying over there!’

The Blak-maan ben down and look heah and deh and seh again, ‘Me na see no tree.’

Now the Vyte-maan is really angry. So he shouts at him, ‘You stupid man, can’t you see that great big tree over there?’

The Blak-maan seh again, ‘Me na see no tree.’

The Vyte-maan is in a rage and yells, ‘What do you mean you can’t see the tree? I saw you see the tree.’

The Blak-maan seh, ‘You saw me see the tree? But you aint go see me saw it.’

I can still hear the voice of my dear friend and first boss, Nick Adams telling me this joke and both of us laughing our heads off. You have to listen to a Guyanese tell these stories with the sing-song tone of their accent and their actions illustrating what is supposed to be happening in the story. I can’t put that into this narrative here. But if we meet one day, remind me and I will tell you the stories in Creolese as they should be told.

Mail took an average of one month to get to Guyana from India. That it actually arrived is a marvel of the system which in today’s email world we seem to have forgotten. But it did come and in the 5 years that I spent in Guyana, I never had a letter that was lost. As postage depended on weight, I used to write on very thin, semi-transparent tracing paper with a very fine nibbed pen to try to get as much matter into it as possible. And since Mr. Gates had not yet created Windows and laptops were not for machines and notebooks had 100 pages of 15 lines each, you could not cut & paste or delete or drag & drop, you needed to write after due thought if you wanted to save yourself the trouble of writing what you had written, all over again. This is how I learnt to express myself in writing.

Thank you, Mr Baig, this provoked plenty of reminisces fro Alastair!

He’s just read a book by Evelyn Waugh, called Ninety Two Days, which is a record of his travels there in the early 30s…he suggests that you might find it interesting.