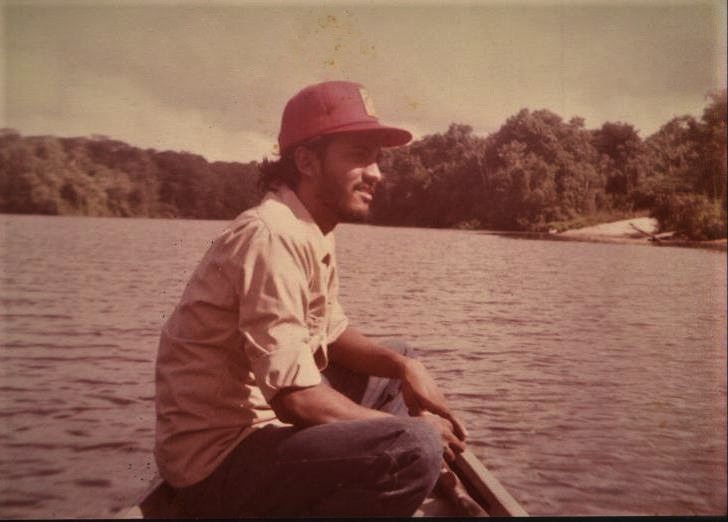

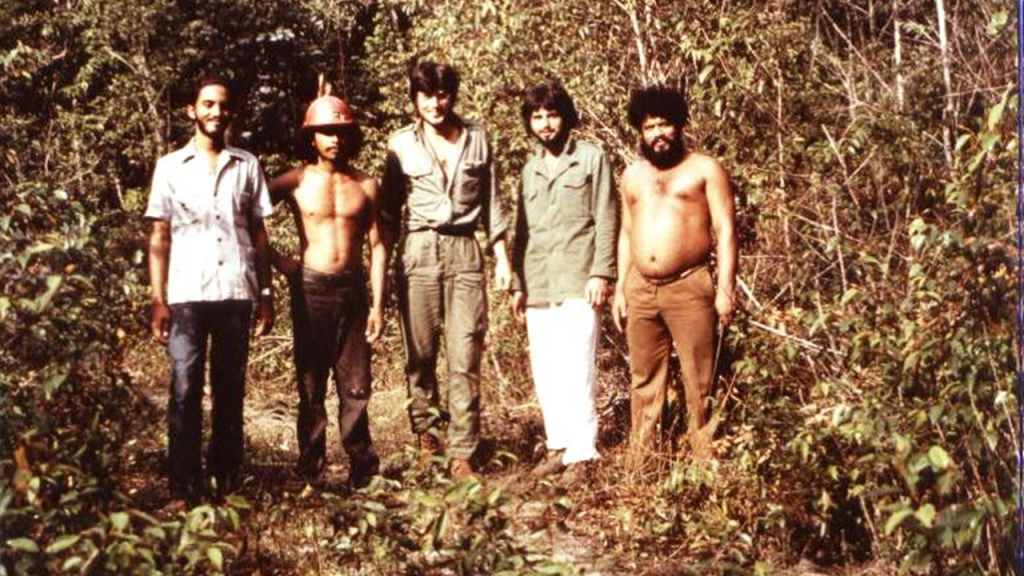

Life in Kwakwani was such a delightful combination of work and ‘play’ that I enjoyed every minute of it. Peter Ramsingh, my friend, and the manager of the sawmill who I have mentioned in other posts, got another friend Leon Molenuex to build a boat for me. It was 18 feet in length with a flat bottom, low sides, and a blunt prow. Its back was flat to fix an outboard motor. It had oar locks and two oars. And it had an ice box in the middle with bench seats, a plank each on either side of the ice box, forward and rear. Peter and I, and sometimes Leon, would load up the boat every Friday afternoon that we could get away and go up the Berbice River. What did we take with us? Hammocks, cutlasses, one single barreled 16 bore shotgun each. Rope, fishing line, hooks and a fishing net. Some rice, cassava, bananas and salt and pepper. And most importantly some chicken guts in a plastic bag. The last being what we called our ‘emergency ration’. Not that we ate them, but if we caught nothing then if you baited a hook with raw chicken guts and trawled them behind your boat you were sure to get some Piranha. Good eating.

It was a matter of honor for us that we would only eat what we could hunt or catch. Since neither Peter nor I ate pork, it took one of the most common items off our menu – Collared Peccary (Bush Pig) that we would be sure to see. But we never returned hungry. We would trawl as we moved along and usually caught some Lukanani (Peacock cichlid, Cichla ocellaris) or Grey Snapper (Acoupa weakfish, Cynoscion acoupa), two of the delicacies of the Amazonian River system and would roast them for dinner. If we were fortunate then either Peter or I would also be able to bag one of the several species of Curassows that lived in those forests. The most common were the Black Curassow (Crax alector) and the Crestless Curassow (Mitu tomentosum). Or even an Agouti (Cuniculus paca, Dasyprocta aguti) which is from the Paca family and a relative of the rabbit and Capybara but much smaller. Game was in such abundance that there was never a trip on which we had to go hungry, but we would also bring back fish and game for Peter’s family and the families of other friends.

We would start from Kwakwani going upriver, travelling until it got dark. Then we would find a sandy spot on the riverbank and camp for the night. That sounds a bit chancy when you read it but we had our spots and knew them well, so we just headed for the first one. A sandy bank was necessary because like all the rivers in this part of the world, the trees of the rain forest trail their feet in the river all along its banks. That makes landing very difficult and camping impossible. So, you needed to look for a sandy bank. That happens at the bends in the river where the river deposits its sand and this collected over the years makes for some very attractive sandy crescents on which we camped.

Our routine was always the same. We would draw the boat up on the bank and I would collect wood for a fire. Peter and I would then sling up our hammocks from the trees that bordered the bank, first clearing the undergrowth around their trunks to ensure that we didn’t end up with unwanted sleeping partners. We would trawl as we travelled upriver and so we would have a couple of good-sized fish in our ice box. Once the fire was lit, Peter would put the kettle on, and I would gut the fish and clean them. Then I would rub salt into the fish and prepare it for the bake. Taking two large yam leaves (or any other large leaf), I would wrap the fish securely in the leaves and tie the whole bundle with a thread. Then I would dig in the riverbank for clay and cover the fish warp with clay and make a ‘brick’ of clay – one for each fish. Once that was ready, I would remove the kettle from the fire, move the coals aside and dig in the sand and bury the clay bricks in the hot sand. I would then put the coals back on top and light the fire again. By the time, our tea was ready so would be the fish. We would then dig out the bricks and crack them open, remove the leaf covering and we had the most delicious baked fish you can imagine for dinner. There is nothing to beat fresh fish cooked with a little salt, in its own juices, with a bit of butter melted on top. We would sometimes end with a banana or two as dessert. And then the tea. Always tea at the end of the day.

When dinner was done, we would climb into our hammocks and chat about whatever was top of the mind until I would hear a snore in response to whatever I was saying. I would know then that Peter was off on his trip to dreamland. The rainforest is a safe place as long as you didn’t do anything stupid like sleeping on the riverbank. As long as you are off the ground nothing bothers you and I am living proof. There are many animals which are dangerous in these forests but none that will take a human being by choice. So as long as you stay out of their normal pathways you will be safe.

Lying in the hammock waiting for sleep to come, I would listen to the sounds of the forest and try to identify each one. The Amazonian rainforest is a rather silent place in the night, unlike Indian forests. The animals are less vocal and the forest itself muffles sound thanks to its density – you don’t hear much except insects. If you are near the river there are not many mosquitos but you do get vampire bats and so you need to cover up unless you wish to be bitten by one of them. That doesn’t turn you into a vampire or anything so romantic, but the wound can bleed for a long time as there is heparin in the bat’s saliva which prevents blood from clotting. In addition, I am sure vampire bites are not exactly what any doctor would order so it is better to stay off their menu.

Early the following morning, we would start out at first light, or sometimes even a bit earlier, going over what looks like boiling hot water because of the ‘steam’ rising from it. That ‘steam’ is the mist that gets created when the warm water vapor laden air meets the cold river surface and gives the whole atmosphere an ethereal quality. Engine buzzing with Peter at the rudder, we would travel in companionable silence, eyes ever watchful for floating logs. These were the only real danger because if you hit one full tilt, it would take the bottom out of the boat. A fate not to be contemplated as the Berbice has Piranha, Caiman, Anacondas, and other interesting forms of life.

The Berbice is a wonderful river that changes its nature all along its course. Downriver from Kwakwani it is deep enough for large vessels to negotiate it. Bauxite ore from Kwakwani would be transported on barges pushed by a tugboat all the way to New Amsterdam on the coast to the smelter. These tugs would normally have a tow of four barges; each sixty feet in length which when fully loaded would sink to their gunnels with the weight. The tugboat captain’s job was a very complex one, negotiating bends in the river a hundred and fifty feet ahead through frequent blindingly heavy rain showers and through the night. Since tugboats and barges are about the clumsiest of watercraft and with the kind of weight the barges carried, this was no mean task. It was a tribute to the training and skill of tugboat captains that in the five years that I lived in Kwakwani, I never heard of any instance of the barges heading out of the river, cross country across the rain forest.

Going upriver, however, the nature of the Berbice changes. It is no longer the deep river that it is at Kwakwani and below it but spreads wide and shallow with frequent sandbars; so shallow in places that one could easily wade across. So much so that on occasion we would have to pull in the outboard motor and drag the boat over the sandbank. In this also there was a twist. In this river sand, there were two kinds of dangers. One that it could be quicksand with so much water under it that if you stepped into it, you could easily sink in over your head and die a horrible death. To guard against that we would get out of the boat only one at a time and hang onto the side of the boat until we were completely sure of our footing. Only then would we let go of the side of the boat and then the other person would also get off and we would drag the boat over into water deep enough to float it. Mercifully, and that was the reason for it, a flat-bottomed boat will float in a few inches of water, unless it is heavily laden, which ours tended not to be.

The second danger was that of Stingrays. These are freshwater rays with a poisonous sting in the tail. Their favorite pastime is to lie buried and invisible in the sand of sandbars, just under the surface and wait for something to come within range and then they would sting by shooting a poisonous spike into it and then wait until it dies to eat it. Their normal prey is small fish but if you were to step on or close to one of them, then they would sting you out of fright. I am sure there are more painful things in life than a stingray sting—I just I don’t know what they are. And if you happen to be allergic to the poison then 50 kilometers up the Berbice River in the middle of the Amazonian rain forest is not where you want to discover this.

Even if you are not allergic, the sting means several days of fever, swollen lymph nodes, swollen foot, and almost incapacitating pain. So, what we would do is to put on our boots before we stepped into the water. Alternatively, you could use a stick and push it in the sand ahead of you as you walk to ensure that you disturb the Stingray and drive it away before you get too close to it.

As we went upriver, we would sometimes pass single houses on stilts on the bank of the river with a little patch of garden at the back growing cassava, banana, and a couple of jackfruit trees. The house was one large room built on a high platform with a leaf or grass thatch. The walls were of woven mat with holes for windows. There would be a couple of dugout canoes tied to one of the poles with a rickety step going up to the platform. Children playing on the step or in the canoes would yell and scream at us with great excitement and delight. If we had time we would stop by and pass out some sweets or bananas that we would carry for such occasions. Otherwise, we would wave to them and they would continue to wave and yell until we rounded the next bend of the river out of sight. I always wondered what would make a person go and live so far up the river in the middle of nowhere, alone without access to electricity, medical aid, and schooling for his children, and without any amenities. These Amerindians would hunt, gather honey and balata (wild rubber latex) and farm a little and would occasionally come to Kwakwani to buy a few things and sell their balata and honey and some wild meat. But they would not work at a regular job for love or money nor would they live closer to town. They preferred to live miles upriver and paddle their canoes several hours to get to Kwakwani and longer to return, paddling against the current on their way up.

The children help the parents in the slash and burn farming, collecting honey and tapping wild rubber trees for latex (balata) and in trapping and hunting, mostly with bow and arrow and spear. Very few Amerindians had guns but given their amazing woodsmanship and tracking and trapping skills, they never went hungry. In their free time the children would race each other or leap into the river from the house platform or the top of the step. Given that the forest is hot and humid most of the time, spending time in the river is a decidedly pleasant thing to do. But what amazed me is that they did this in a river which had Piranha, Caiman and Anacondas, without any fear of any of them. I always wondered whether any of them disappeared from time to time, but I never heard of any such incident, so am led to believe that either it didn’t happen or that it was accepted as the price of living in that neighborhood.

It was a wonderful experience, buzzing along up the river hour after hour, listening to the sounds of the forest. Macaw pairs flying high over the canopy, talking to each other. Macaws believe that conversation makes for happy marriages and it seems to work for them as they pair for life and talk all the time. Toucans screaming whatever they scream about. The booming call of the Howler Monkey sentinel answered by his counterpart in another part of the forest. The sudden crash in the undergrowth as you come around a bend and scare away something that was drinking at the edge of the river. From the sound of the crashing, you can guess whether it was a Collared Peccary or a Tapir. Deer and Agouti move very quietly, and you wouldn’t even know that they had been there.

One weekend we decided to go as far as we could and eventually, we must have gone more than a hundred kilometers when we came to place where the river widened into a huge pool. We entered the pool from the side that the river flowed out of. On the opposite side where the river flowed into the pool was a series of rapids and short waterfalls. The sides of the pool were sandy and made excellent camping ground. We were delighted with the whole prospect. It was an exceptionally beautiful place indeed. Peter and I decided to camp for the night and pulled in and dragged the boat far up onto the sand. No telling if the river would rise in the night and float the boat away. That is not a prospect to be contemplated, being a hundred kilometers or more in the middle of nowhere without a boat. Trekking through rain forest is not an occupation to be thought of easily.

I got the fire going while Peter hung up our hammocks. Suddenly, I noticed on the far end of the pool near the rapids, a permanent structure on a concrete platform, a room roofed with corrugated iron sheets. It looked like a government structure and I wondered what it could be. Once we’d had our dinner and before it got dark, we decided to go across and take a look at what it was. When we tied up to the little jetty there, an Indian Guyanese man came down to the water and greeted us. With him was an American who looked like a technician by the way he was dressed, in overalls. We made our mutual introductions and it turned out that the structure was a weather monitoring station with some equipment from Motorola, which needed repair. The American engineer was from Motorola and had come to repair the equipment onsite. In the course of conversation, he asked me where I was from. I told him that I was from India.

He asked me, ‘Where from in India?’

I replied, ‘Hyderabad.’

He got very excited and told me, ‘I have been to Hyderabad. I have a friend there. His name is J. J. Singh and he works at the Administrative Staff College. Do you know him?’

I rolled my eyes and said, ‘Do I know him? Of course, I know him! But look at this, what is the probability that I would be in the middle of the Amazonian rain forest, a hundred kilometers up the Berbice River, where I would meet an American who I had no idea would be there and we would have a mutual friend? If there had been someone betting on this, we would both be millionaires, man!!’ And we both had a great laugh. Whenever someone tells me, ‘It’s a small world’, I tell them, ‘Yes, but much smaller than you think.’ And I tell them this story. To date, nobody has told me a story more unlikely than this.

Peter and I would sometimes go fishing in the night. If you floated with the current down the river keeping to one of the banks and shone your torch into the water, you would attract fish to the light. Then it is a matter of spearing them. The spearing takes some skill because thanks to the error of refracting light in the water, the fish is not where you see it. But once you get the hang of correcting for it, it is a simple matter of spearing the fish and pulling it up flapping on the end of your spear. I have seen Amerindians even shoot fish with their arrows with great accuracy. They would have a light line tied to the arrow so that they could then haul it in.

On these excursions, if you shone your torch over the surface of the river, it would appear as if the water were sprinkled with diamonds. Shining stars, eyes of Caiman, young and old, out fishing, floating on the river with only their eyes and nostrils above the surface. Like alligators and crocodiles, the Caiman is a fish eater but not above taking the unwary to add variety to his diet. They also eat turtles and so their jaws are adapted to taking in broad prey and exerting tremendous biting pressure to crack their shells. You definitely wouldn’t want to go swimming with a Caiman, especially as a big one can grow to 6 meters (20 feet) in length. Caiman are seen as a nuisance by riverside dwellers as they destroy fishing nets and sometimes attack cattle. I hate to think of little Amerindian children playing in the water all day jumping in and out of it – I expect when one did not show up at home at night is when you knew that something had happened. But at night, the shining eyes used to be an amazing sight and I loved to shine our torch and look at it. During the day you would almost never see Caiman as they lie up in the mouths of creeks that flow into the Berbice in the thick shade of riverside trees, waiting for the night to descend. What we would see a lot of in daylight was Terrapins; little turtles taking the sun on any available rock, log, tree root or even floating debris. They would sit there with their necks stretched out and a quizzical expression on their faces. If you got too close, in a flash they would slide into the water, much faster on their feet than you would likely give them credit for.

It was a beautiful idyllic existence doing all that I loved to do and doing it all for free. I know that you could spend thousands of dollars to take a trip up one of the major rivers in the Amazonian system, camp on a sandbank by a fireside and spend the night in a hammock gazing at the stars over the river. And I did all of this and more at will, free of cost. I am indeed extremely fortunate and most grateful to Allahﷻ for it. Early in the morning, well before dawn Peter and I would wake and take our boat to check the nets which we would have tied the previous evening at the entrance of several creeks that flowed into the Berbice. Fish go up into the creeks to feed in the night and a net across their path is an easy way to ensure that you don’t come away empty handed. We would float on the current or paddle and pull in the nets and haul in our catch. Then as the sun rose, we would return to our camp to cook our breakfast.

One day as usual we went inspecting our nets while it was still dark. We floated silently downriver to the first creek where we had tied a net. Peter steered the boat and I sat at my station in the prow looking ahead. The night was very silent, waiting for dawn, when all hunters and prey are at rest. The Howler Monkeys are not awake yet, nor have the Macaw flights started. Everything is waiting for the sun. At that time almost nothing moves except hunters like us, checking on their traps, snares, and nets. We reached the creek mouth and Peter pulled up the net. The boat dipped with the weight of what he was pulling. “Man!! Looks like we got something big!!” he said. That river at that place was home to the largest freshwater fish called the Arapaima and so I was very excited. But what came up was something totally unexpected and unwelcome.

Looking at us intently was a flat triangular head with sharp bright eyes – a full grown Anaconda which had got himself entangled in the net. He had gone after a fish that was caught in the net and having swallowed it along with the part of the net that it was entangled in, he tried to get out and managed to get himself into such an unholy mess that he was completely entangled. He was definitely not amused at his plight and hissed at us to tell us what he thought of us. He was so big that pulling him into the boat to try to free him surely meant sinking the little boat. Leaving him as he was would condemn him to a slow and painful death as he was so entangled in the net that he could never free himself from the nylon mesh. So reluctantly we decided to shoot him. While Peter held the net out on an oar raising the part where the snake was entangled, I shot his head off with a 16-gauge shotgun that I always carried on these trips. The snake went into such a convulsion that had Peter not wisely dropped him back into the water he would have upset the boat and dumped us both into the Piranha infested waters of the Berbice in the darkness of pre-dawn. A decidedly unpleasant prospect.

Once the snake was dead, we tied the net to the side of the boat and rowed back to the camp. We pulled the boat up on the sand and cut the snake out of the net, completely ruining it in the process. I was not amused as nets were valuable. Then we measured him. He was 16 – feet long and both Peter and I together, could lift him only with great difficulty. I was very sorry to have killed such a fine animal, but we had no alternative. We took off his skin and I had it with me until I met a young man called Fridolin Stary who had come from East Germany to Guyana on holiday. He liked the snake skin so much that I gave it to him. Thanks to the power of the internet, I found Fridolin, almost 30 years later. He was by then, a top manager of a chemical company in Germany. He remembered the time we spent together, and we exchanged some mails and met in 2011 when Fridolin came to India. It was a lovely meeting, as if all those decades had not intervened at all. Fridolin came home and we had a typical Hyderabadi meal, which he seemed to love. We discovered that we share many core values, respect for the environment, love of the wild, importance of justice, and owning responsibility for our actions. Small world made smaller and flatter by the internet.

Comments (0)

Comments for this post are currently disabled.

Loading comments...