In my Leadership Development Consulting practice, one of the things I teach is team-building. Little do people know that what I teach is what I learnt on the ground in Guyana in the bauxite mines and in India in the tea plantations. As my favorite Western novel writer Louis L’Amour puts it, “If I tell you about a stream, it is there, and the water is good to drink.” I can say that anything that I teach about leadership and team-building; I have tried it and it works.

As my dear friend and fellow planter Sundeep Singh put it, ‘The learning in the initial years was amazing, covering a wide gamut of activities, labour management, construction, stores, budgeted finances, work planning and allocation, farming, production etiquette and outlook to name just a few. Here I must add, the inputs for each of us were generally the same except that each was responsible for his own growth, learning from lessons and accepting the truth. Further, the challenges of loneliness and channelization of focus and energy, as life outside of work was a relative void.’ That is why I tell people, ‘If I can do it, so can you. Provided you are willing to try.’

My greatest gains in Ambadi were to do with conceptualizing learnings, about the importance of mentoring to empower front-line staff to take decisions and ownership. The results that we achieved had directly to do with our success in both areas. We took a group of discordant individuals and built them into a highly synchronized team that functioned as one person. We enabled people to see their strengths, to believe in themselves, to own responsibility, and to actively seek accountability. We took people who always played doubly safe and converted them into risk takers who were not afraid to take initiative. And we did all this in a period of less than one year.

If I reflect on what the key initiatives were, I can think of two major ones.

- The importance of making mistakes

I managed to convince my team of the importance of making mistakes. I remember the looks of puzzled surprise at this term when I first mentioned it. Mistakes were things you tried to avoid. If ever you did make one you tried to hide it or to blame it on someone else. And eventually if all else failed you resigned yourself to bearing whatever punishment that mistake attracted.

But here was Mr. Baig, saying that it was important to make mistakes. Obviously, this was a trap. So, we will do what all sensible people do: silently wait and watch. That was my biggest challenge; to get people to change their mindset. Once I had announced the importance of making mistakes, I watched for the first person who made a mistake. Naturally, everyone being human, it happened sooner than later. Then I called the person and told him to give me a written statement of what happened, why he believed it happened and what must be done to prevent that particular thing from ever happening again.

I started weekly Staff Meetings and these statements would be discussed in the staff meeting where others would add comment on the incident and the recommendations of the individual involved. The incident was treated as a normal case study. Not as something that needed to be punished. Then once the lessons were clear to all, the matter would be closed. Nothing more to be done on the issue, except that I would silently monitor it and the individual for a while to ensure compliance with whatever had been agreed.

No punishment. Not even a verbal reprimand. In contrast, if the analysis was particularly well done and the solution was a good one, the maker of the mistake would be appreciated. Sometimes I would pull his leg and ask him what he had done with all this intelligence at the time of making the mistake. Or I would say something like, “Thank you very much for teaching us this lesson.” The person would look a little sheepish but that was all. The lesson was learnt, not only by the one who made the mistake but by everyone. So, the learning was actually very cheap because the same mistake need not be made multiple times for others to learn. The only caveat was that you could not repeat a mistake. If that happened, then there would be a reprimand because you had demonstrated that you had not learnt from the previous time. And that was not acceptable. In fact, that almost never happened. People are intelligent and nobody likes to look like a fool.

As I mentioned, once people started seeing for themselves that making a mistake was not necessarily bad, their risk averseness decreased. As long as you made a genuine mistake and not a deliberate misdemeanor, and as long as you could demonstrate your learning and create a system where it would not be repeated, there was no pain associated with the mistake. I encouraged other good practices like maintaining a diary. This was useful when we needed to recall some action or incident and memories were foggy. Another one was to write down a plan of action before you actually take the action so that if something went wrong you know exactly what happened and are not trying to recall what you had done or intended to do. Prior planning as well as documentation encourages deeper thought and reflection which can only be beneficial. To ensure that we did not get bogged down by too many planners, I made a rule that you had to put a deadline to everything. So, any time anyone submitted a plan we asked for a deadline if it wasn’t there. We also made the weekly meeting the place to initiate all these actions. The idea being that before you launched off something, you brought it before an assembly of peers who helped you to evaluate your plan. This also ensured more rigor in the whole exercise because people knew that if they submitted something that was half-baked it would be pulled apart in the meeting.

My role in all these meetings was mostly to listen and watch and sometimes to ask questions. Once people grew comfortable with speaking before others and asking and answering questions there was no holding them back. Sometimes there would be so much participation that it would be difficult for me to get my point across. I considered that to be an indication of interest and commitment and encouraged it. Another trend that took off was that the individuals who intended to present something at the staff meeting would do a little pre-show to their colleagues who had specialized knowledge. For example, they would run some of the numbers by the accountant to make sure they had done their sums right. I encouraged all this informal communication and collaboration because it is a wonderful team building process. The whole essence of team building is to help people see how they need the other person to succeed. And when this started happening, I knew we were on the right track.

Having said all the above, let me also say that the most difficult part is to sit in silence and see a mistake happen. All because you want to turn it into a learning situation. But there is no alternative to this patience. Naturally, one does not need to self-destruct in the process, and it is possible to contain the magnitude of the mistakes so that the learning takes place at a manageable cost. The crux of the matter is that you need to allow subordinates to make mistakes and then guide the learning. This anxiety is compensated by the pleasure of seeing fewer and fewer mistakes happen over time as people get more and more proficient in their roles. The practice of sharing learnings and Best Practices ensures that the learning gets maximum leverage. Also, people are not ashamed or afraid of making mistakes as they know that there is no punishment, provided they use their heads and can share their learning. As a result, people generally exercise more care and the number of mistakes decreases. Finally, the biggest benefit of this method is the exposure and appreciation that people get when they share their learning and best practices and have a platform to talk about their gains. This encourages them to share information and creates organizational learning as distinct from individual learning. In my view this one benefit is worth more than anything else.

- Mentoring

The second learning that I gained in Ambadi has to do with mentoring and people development. The current ‘lack of loyalty’ of millennials to organizations that employ them is a problem that some managers of my generation find exceedingly difficult to understand or accept. For most of us (and even more so for our parents’ generation) we joined one company and worked there until we retired. Where we changed jobs, we made perhaps one or two changes in our entire careers.

Loyalty was a major virtue and changing jobs too often was considered to be an indication of disloyalty, exceeded in villainy only by thievery. Being conscious of your own gain was selfishness, yet no one questioned the ‘selfishness’ of organizations and employers who after retirement, in most cases, did not even send you a birthday card or show any concern for someone who gave forty years of their life for them. For young people today, an organization gives them the freedom to express themselves, it is a place where they can experiment with their knowledge, from which they expect a challenging environment and a reward in proportion to their contribution.

The key thing here is that they decide what is challenging, what freedom is, and what a reasonable reward is. And if they do not get it, they move on. Attrition is a given in today’s world. And within limits, it is a good thing. I have always believed that it is the role of the leader to create the inspiration for others to work for him. If leaders cannot inspire people to work for them, then there is no good blaming the people for leaving.

I remember doing a leadership development workshop for the middle managers of one of my clients, a large BPO. Attrition was a major problem that they were continuously wrestling with, without success. I gave them an exercise. I said to them, “Please write down three things that differentiate this company from every other company in the market. Things that anyone leaving this company would lose. Things that they can never hope to get anywhere else.” “That,” I said to them, “is the solution to your attrition. If you are clear about why you work here and why this workplace is unique, then you can inspire those who work with you.” Interestingly at the end of half an hour, nobody could make the list.

To try and find answers in our past of how to deal with these attitudes is futile. To react to them from our value system brings about a reaction of ‘punishing’ and ‘getting back’ at such ‘disloyalty’ and only results in more negativity.

It is in this context that mentoring comes into its own. There is no better process for building a robust leadership fabric. Stacks of cordwood that can be pulled in as needed during the cold blizzards of business life. Leadership nurtured from within. Homegrown leaders who push you to excel and to provide them challenges that stretch them and give them the satisfaction of real achievement.

The Mentoring process consists of the following four steps:

- Setting Mutually Acceptable Goals

- Identifying Development and Support Needs for Goal Achievement

- Coaching & Mentoring: Monitoring Progress and prompt Feedback

- Conducting the Evaluation Interview

Setting mutually acceptable goals

Goal setting is the first and most important step to manage performance. The essential thing is to ensure that you only facilitate the process, and help the protégés to set their own goals. Successful goal setting encourages the protégé to move out of the safety of the known, into the realm of the ‘Stretch Goal’. I define ‘Stretch Goal’ as a goal that scares the living daylights out of you, but which also energizes you with great expectation of achievement. If a stretch goal is not scary, it is not a stretch goal. The critical challenge of the mentor is to ensure that he/she builds enough trust in the environment for the protégé to venture to set challenging goals. My own experience and that of other people who I have seen, talked to, and taught during my three decades plus in organizations, tells me that the real challenge is for the mentor himself to not get scared of the ‘Stretch Goal’.

Psychologically speaking, the mentor’s belief in the subordinate ‘comes true’. This is the ‘Self-fulfilling Prophesy’, which is when you unconsciously act to bring to life, the belief you started off with. This can be seen any number of times in leadership situations. If done well, this step is the most energizing experience for the protégé and develops real commitment to the goal. The caveat is that it works both ways. Negative prophesies also self-fulfill.

Identifying development & support needs for goal achievement

Identifying and committing to provide development and support inputs is critical to the Mentor-Protégé relationship and to successful performance. This is where the ‘rubber meets the road’ and you contract to provide the material, guidance, and training that the protégé needs to fulfill the task. This is where psychologically, you are saying, “We are in this thing together. Your success is my success and your failure is also mine.” If you stop to think how true this really is, in any leadership situation, you will understand the importance of doing this step correctly. The caveat in this stage is the enthusiasm that the goal setting phase can generate for both parties. It is sometimes possible to over-commit to giving support and developing competencies that may not be realistically possible. I am not suggesting that you undo the good of the stretch goals here. I am merely saying that it is important to be clear about what you are promising to do in terms of the inputs that the protégé needs and what that you can realistically give. This is not only about willingness but also cost, time, and resources that you will have to think of, some of which may involve other people as well as yourself. Remember that the disillusionment of promising but not delivering is something that you don’t need, and which will undo all the good that you did in building the relationship.

Mentoring: monitoring progress & prompt feedback

Mentoring is a factor of how we choose to look at ourselves and our roles. It has nothing to do with our expected lifespan in the organization. It has to do with a desire to build and to develop others. A desire to share. A desire to extend ourselves for the sake of others. A desire to influence. A positive need for power (not politicking) understanding that it is only through persuading others to share our values that we have our greatest hope of exercising the most influential power…the power over minds.

The leader as mentor is not someone who imposes the “right” way, or someone who seeks to change the way people think to align with their own thinking. Mentoring is about helping the other individual recognize their potential by providing the challenge necessary for them to realize it. Very often this means becoming a mirror for the protégé but ensuring that like a mirror, you don’t judge. Talking mirrors exist only in fairy tales, not real life. Your job is to merely reflect the image with integrity and leave the protégé to decide to act on his own. This can sometimes be very difficult indeed, but any attempt to force the issue by ‘suggesting’ what they should do or how they should act is counterproductive as it creates dependency and does not build the decision making capacity that is essential if the individual is to sustain their growth.

There is always a great danger in mentoring, of becoming the proverbial ‘Guru’, who has a stake in keeping the protégé dependent on him. This happens when the mentor becomes the de facto decision maker in the person’s life and tells them what is ‘good for them’. Interestingly, my computer underlined the word ‘de facto’ as a spelling mistake and suggested ‘defecate’ as the alternative. Maybe that is the unconscious expression of the reality about such guru-ship. This seductive process is also aided and abetted by the protégé (who another friend calls, ‘the demented’ – defined as one who accepts a mentor) to listen to this wise counsel and accept the gyan (knowledge) as gospel truth about himself. This is especially ‘useful’ for the individual who does not want to take the trouble of thinking for himself and holding himself accountable for results. Somewhere the unconscious belief seems to be that, ‘If I don’t decide what I should do in my own life and go by the advice of my mentor, then I will not be ‘held’ responsible for the (possible) unpleasant consequences. It will be the mentor’s fault, if I fail.’ It is a vicious cycle which both the mentor and the ‘demented’ collude in.

Mentoring in a truly developmental way has two major challenges from the perspective of the mentor. The first is to continue to mirror and reflect what the protégé projects, so as to help him see the real issues which are either hurdles to his development or sources of strength that he can call upon to propel himself onward. Bringing to the interaction all the benefit of your life experience, yet not allowing any of it to become an imposition on the direction the protégé should take, is a great challenge. In my own experience as a mentor, what helps is the humility to remember that my experience is after all, just that…my experience. And that my future and my potential are quite different from those of the protégé.

The second great challenge in mentoring – and this is especially true where the protégé is a subordinate in the organization – is to recognize greater talent and ability, greater potential for development than your own and to nurture it. Not to get threatened by it or to try to suppress it. This is often an insidious, unconscious process that we succumb to and then seek to destroy the individual who we choose to see as a ‘threat’. I remember encountering such ‘mentors’ early in my career as a consultant. I was perplexed and anguished at experiencing tremendous aggression and hostility under the surface from the very people who I had accepted as mentors. I could not understand it at all and spent many days agonizing over what ‘I’d done wrong!’

Even when I shared my confusion and anguish, it was denied and cast aside, and feelings of guilt were projected on me for my alleged lack of loyalty. “How can you even think this about us?” It was only when I shared this experience with another friend and mentor, that I saw the real issues at hand. He said, “You are not a threat. You are a challenge to their competence. They choose to view that as a threat. They can also choose to view it as an additional resource and build on it. The choice is theirs. Your choice is to decide how much energy you want to invest in coping with this hostility.”

My greatest learning in this was the fact that I still had to make the choice of what I would do in the circumstances. My friend had merely clarified the issues that faced me without attempting to tell me what I should do or what he would have done in my place. In this case it was the choice of having the ‘support’ of these individuals in my life as a fledgling consultant or to risk the danger of solo flight when I was still uncertain of my wing-power.

I chose the latter, as I felt that coping was taking up too much of my energy which I could put to productive use in building my own business. Subsequent events proved me right and added to my learning. It is a very painful decision indeed for a protégé to take, to give up a mentor who is not adding to his/her learning and even more painful for the mentor to accept this fact. However, this extreme step may be needed if the relationship becomes a net energy drain instead of a source of encouragement.

I am reminded of my classical Hindustani sangeet (singing) teacher’s words. “Artists are made up there,” she said pointing to the sky. “We only teach people how to sing. So, after a time the teaching ends. The learning however, never ends. Every discovery that we make about ourselves and our ability is a new lesson in how far we can go.” It is only when we try to exceed our ‘limit’ that we learn more about how far we can really go. Each attempt has the potential to show us that we can do more than we had thought possible. It is the role of the mentor to enable that leap of faith for the protégé. And that can only be done if the mentor does not project or impose his own fears on the protégé. The essence of mentorship is to remember this and to always try to facilitate this journey of self-discovery without imposing our own insecurities and fears or even our life lessons on the protégé.

My own experience in being a mentor as well as having had many mentors is that once we decide to face the challenge of our own growth that the protégé unconsciously demands of us, then we set up this very fruitful and rewarding relationship where the mentor and the protégé fuel each other’s learning. One challenges the other and mutually they create an environment that demands growth and supports it. This is what I call relatedness. It is the ability to continue to relate and build the relationship through changed circumstances and changed phases of life. It is when this ability fails that the so-called generation gap develops. But when you can continue to relate to the protégé through his journey of growth by constantly challenging yourself and growing with him then your relatedness becomes the greatest advantage of mentoring and its real pay-off.

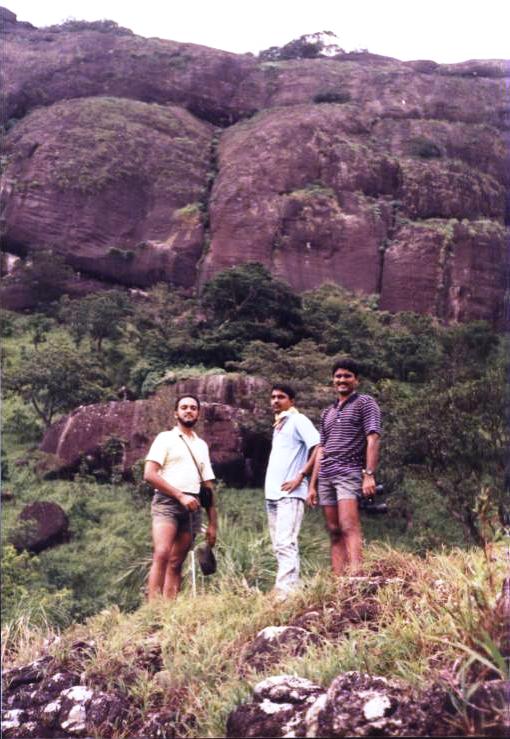

One final thing which helps team-building and that is the importance of shared life experiences. I don’t mean work related but others, fun things. Among those was a trek to Manjolai, the BBTC tea estates on the mountains, that Arun, Roshan and I did. As Wiki tells us: Located between elevations ranging from 1000 to 1500 metres, the Manjolai area is set deep in the Western Ghats within the Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve in Tirunelveli District. Located on top of the Manimuthar Dam and the Manimuthar Water Falls, the Manjolai area comprises tea plantations and small settlements around them; Upper Kodaiyar Dam; and a windy viewpoint called Kuthiravetti.The tea plantations and the whole of Manjolai estates are operated by the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation Ltd on forest lands leased by the government of Tamil Nadu.

Kanyakumari district where Ambadi is located is in the plains in which the feet of the Western Ghats are grounded. But if you climb up from the plains, straight up the side of the mountain, about 4500 feet later, you will stand on top with the plains at your feet. There is a more normal and far easier way to get to Manjolai by driving up the mountain from Thirunelveli. But satisfaction is directly proportionate to difficulty and so we decided to trek up the mountain.

One Sunday morning we started at daybreak. Arun, Roshan and I. When my friend Suryaprasad, the ASP (Assistant Superintendent of Police), Thuckalay, heard that I was planning to go he told me that he would like to come along and would inspect the Police Station at the top of the mountain in Manjolai. I asked him if there was much crime in that area. He told me that in the past year there had been two thefts. Safe place, you would say. The trail was narrow and very steep. In places we had to slash our way through undergrowth. The trail existed to service a ‘ropeway’ (winch powered car going up the mountainside) that was used to take supplies for Irrigation Department officials in Manimuttar Dam. The track was hardly ever used and was uneven, deeply scored with gullies made by rainwater runoff and had long grass with serrated leaves which tried their best to flay the skin off your bones as you walked. Yet, we climbed.

As we climbed, the sun rose higher in the sky. There was no shade as there are no large trees on the mountainside. Kanyakumari is a hot and humid place and climbing mountains is not the most comfortable activity. Add to it scratches from thorns, insect bites, sweat pouring out from every pore and snaking is way down your back, along your legs into the scratches and very soon you start to question your sanity. This is where the ego comes into its own. It is almost the only positive use of one’s ego. It keeps you going. It is a good thing that in such situations, people are short of breath and hellbent on keeping up the pretense of toughness, perseverance, tenacity, and grit. That makes them keep their mouths shut. If one of us had simply said, “How many of you think that this was a bad idea?” We would have been going back downhill in a jiffy. But that did not happen. We continued to climb.

After about two hours of grueling effort, calves and thighs on fire, chests heaving like bellows, we reached a halfway point. It was a bench of rock that we could rest on for a while. One thing about halfway points when climbing mountains; they are also the point of no return. After that you can only go one way; up. Going down from the halfway point is even tougher because the descent is always more taxing on the knees and thigh muscles than climbing. We drank a little water. Can’t drink too much or you get cramps. Then back to the climb. “This had better be worth it”, I am saying to myself. Then as we climbed higher the air started to get cooler and the climbing became easier as we got our second wind.

Eventually as in every climb, if you do it long enough, you get to the top. So, did we. We turned around to look at where we had come from. And what did we see? A rich carpet of many shades of green, with huge splashes of quicksilver. Rice fields in various stages of growth with ponds of lotus and lilies. Too far to see the flowers but the water shone like mercury in the sun. Raise your sights a tad and it turns blue, first hazy, and then clearer and then way out in the distance a deep blue which looks like the sky but isn’t. That is the mist rising from the rice paddies, the sky at the horizon and the blue of the Indian Ocean. Then up the mountain comes a breeze. So cool and refreshing that I can still feel it in 2020, knowing that the coolness of the breeze is in proportion to the effort made to get to this place. The harder the climb, the hotter the sun, the more we sweat, the cooler and more refreshing, the breeze. That is life itself, isn’t it?

The story does not end here. Our climb had ended but not our trek. We still had about 8 miles to go to get to the Manjolai Club where we planned to rest and get something to eat. So onward we marched. The lovely surprise was that when we reached Manjolai Club I found my good friend Ricky Muthanna, the General Manager of BBTC, the company that owned the tea estates there at the club. We got a wonderful warm welcome and great food after which Ricky insisted that his car would take us back home.

In conclusion of this chapter of my life, let me share with you some other learning about organizational life and career management. Your career is, in fact, in your own hands and the sooner you learn how to manage it, the better off you will be.

Political skill is essential for survival and growth in organizations. I learnt that political skill does not necessarily mean that one must lie and cheat or compromise one’s integrity. I learnt that being frank, open, and honest must be tempered with wisdom and social skill. It is essential to speak the truth. But one has the liberty to decide when, where, and how to speak out. It is wise to think a little about what one wants to say, how exactly to say it, and the ultimate result that one wants to achieve. As they say, ‘It is knowledge that a tomato is a fruit but wisdom not to put it in a fruit salad.’ I learnt that it is not always necessary to take issue or respond to everything. I learnt that cynicism is detrimental to health and spirit. And success often hides in an unknown place behind disappointment. Fear of failure prevents us from leaving the safety of the known for the uncertainty of the unknown. But without it, there can be no progress.

I learnt that one’s sense of achievement and self-esteem is not rooted only in one’s work or employment. One can find self-fulfillment in areas outside one’s formal employment. I found the joy of writing and reading, but primarily writing. Writing opens the possibility of communication across boundaries of geography and time. I learnt that in the corporate world, and indeed in all of life, you do not always get what you deserve. It is essential to have a clear goal, a roadmap to get there, and a strategy to take you on that road. I learnt that if you make even a small effort in this direction, you will win, because far too many people are simply sitting and waiting for ‘good luck’ to happen to them. Good luck, I learnt is where opportunity meets preparation. When one is not prepared, then all opportunities are ‘difficulties’ and can’t be leveraged.

I learnt the importance of other people in corporate life. I learnt that success depends on our ability to inspire others to pull in the same direction as us. And that, this is a matter of trust. How much do people believe that they will win and achieve their own goals if they follow your lead? For in the end, people work for themselves, not for others. They work for others who they believe can help them achieve their own goals. I do not mean to sound cynical. This is the reality as I experienced it and something that shows us what we need to do to influence others. Show them how they can win by working with you and you will have all the followers you need. Everyone listens to the channel, WiiFM (What’s in it for me?)

I learnt that I am responsible for my results. I have the power to decide what I want to do with my career. Nobody can make or break my career unless I help them to do so. I have the choice to help them to do either. I learnt that it is not necessary to break relationships in order to assert your own rights and that people respect you more if you stand for the right things, even if in doing so, you have to go against them. I learnt that the way to do this is to show that you are not opposing them, but that you are asserting something that is legitimately your right. And that this conflict apart, in which you are on the opposite side of the table from them, you are willing and able to help them in all other things. This ensures that the conflict never degenerates into a personality clash and the issue and the people involved remain separate. I learnt that when one is faced with unreasonable behavior, the stronger person is the one more in control of himself. That the one who can control his anger is stronger than the one who loses his temper. I learnt in the end that the strongest is the one who can forgive the wrongs that have been done to him for that truly takes courage and character. As they say, most people can stand adversity. If you want to test a man’s character, give him power.

As I end this post, I hope that when I am judged, I will not be found wanting and that in the balance, my shortcomings will be outweighed by my contribution to the lives of others.

Superb piece of writing, and advice which transcends the corporate world into life itself. I, especially, like the bit on mentoring. As for building a team in Ambadi, and the methods used, they were merely tools. Unless the people see certain qualities in their leader, the desired results will never be achieved. They need to know the leader can be trusted. Loyalty is a two way street and they expect the leader to be loyal to them too. They need to be sure that he has their back, come what may. The leader also needs to know his job and… Read more »

Very encouraging advice Mirza sahab….much needed today, amidst a growing landscape of scattered individual brilliance. Thanks

Salil Dutt

You tell the most vivid stories, tapping into all senses. “Are you willing to make a mistake and share a mistake” is a go-to interview question I ask. And as you wrote, “What did you learn from the mistake?” Thank you!

Shykh Yawar’s writings and talks always contain pearls of wisdom.

This article is more impressive as it’s from own experience and learning from the nature.

Making mistakes, encouraging colleagues to take risk, mentoring them without being critical, developing trust, setting right goals are truly empowering techniques to build winning teams.

You’re a gifted writer! You’ve had an exciting career Yawar. And thank you for sharing the lessons you learnt in your career and your life. They’re brilliant!

Love your line about channel WiiFM. 🙂 Very true indeed!

A very detailed article on team building with examples from personal experiences.

There is no better opportunity to build teams than in the plantations.

Well done Yawar!