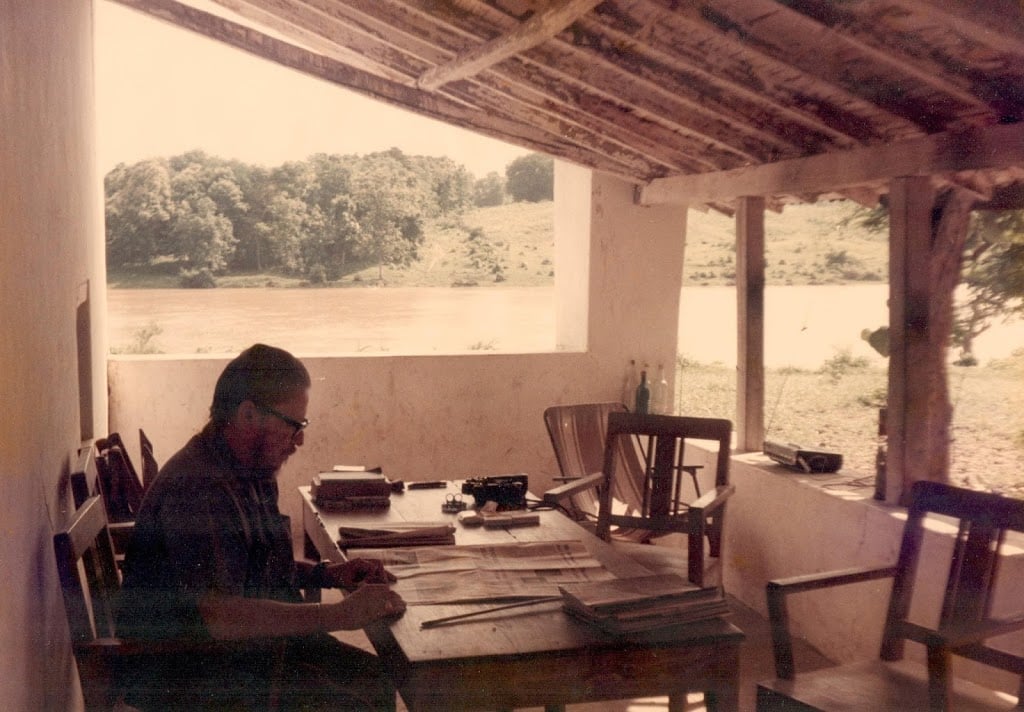

Uncle Rama at his desk – River Kadam in full flow

Time, late 60’s to middle 70’s. I used to spend all my school vacations and later, whatever time I had free from college with Uncle Rama in Sethpalli. Sethpalli is a small village about two kilometers from the bank of the Kadam River, with agricultural fields between the village and the river. Uncle Rama’s farmhouse was on the bank of the river itself, with his farmland behind and to the sides of it. The farmhouse consisted of a long veranda with a waist high wall, that ran the length of the front of the house, facing the river. The veranda had one door leading into the house, which opened into the central of three rooms. The middle room which you entered from the veranda was a passage cum dining room with one bedroom on either side. Both bedrooms had windows opening into the veranda as well as to the side of the house. The dining room had no windows, just the door leading into it from the veranda and another leading out into a veranda at the back of the house. As you entered this back veranda from the dining room, to your left was the kitchen, the domain of Kishtaiah the cook and opposite it, on the other end of the veranda, the bathroom. That literally meant what it was called, a room to have a bath in. It had a stone floor sloping gently to a drain in one corner. Water came in two buckets, one cold and one hot and you mixed it to the temperature you wanted.

If you sat on the veranda, which was the living room of the house, you looked out over a waist high wall which was also a seating arrangement, out to the river. Between you and the river were three massive tamarind trees, easily over fifty years old, perhaps more. They grew within touching distance of each other so that their branches held hands high in the air. The result was the densest shade you could imagine. There is something about the shade of tamarind trees that is cooler than the shade of any other tree. Maybe it is my imagination but I recall the countless afternoons that I spent lying on a charpoy in that shade, gazing up at the canopy of tiny compound leaves, marveling at the multiple shapes and shades of green. A few yards beyond the trees, the land sloped steeply into the bed of the Kadam River. The channel itself meandered from one bank of the river bed to the other depending on where it had been flowing most vigorously in the monsoon. In the summer, the channel was a trickle which you could cross literally by jumping over its narrowest part. But in the monsoon the Kadam flowed strong and deep from one bank to the other. I never measured the actual width of the river at the farm but I think it was probably about half a kilometer in width.

My almost invariable daily routine was to take off into the forest after breakfast, with Shivaiyya as my companion and return only after dark. Shivaiyya was one of the people who worked on Uncle Rama’s farm and like most of them had no fixed duties. He was there to do whatever needed to be done which during my visits was simply to be with me. He was older and far wiser and his job was to see that I didn’t do anything stupid while we were in the forest. He was a great friend and we shared our food and an occasional beedi, especially on a very cold night when we would sit up at a Sambar rolling spot, waiting for Sambar to come down from the hills. Naturally this would be only towards early morning after any Sambar had been and gone, because a beedi is the surest way to warn off any animal.

I would either not eat lunch at all or take a roti or two in a small metal tiffin box with some mango or lime pickle to eat for lunch, which Shivaiyya and I would share. But most often we just drank water from the deep pools in the river, left over from the flow that dries up in the summer. If you spread your handkerchief on the surface of the water and suck through the cloth, you manage to get some clean water to drink. This method will not save you from chemical pollution, but mercifully those were the days before we destroyed our rivers. Then we would sleep in the heaviest shade that we could find, which was not easy in the summer because the forest (and teak plantations) are deciduous and have hardly any leaves. But if you went to a bend in the river which still retained some moisture, you would get some trees with leaves and welcome shade. Sleeping in a forest with tigers and leopards was not without its hazards, but the tiger is not as opportunistic as the African Lion and so you are quite safe in these forests. I am living proof that tigers don’t eat junk food and recall with great pleasure the many times that I have slept the deepest, most peaceful and comfortable sleep of my life in a sandy stream bed or in the shade of a forest giant.

Shivaiyya and Kishtaiah (40 years after this story in 2010)

One morning we took off on our walk, Shivaiyya and I, with me carrying a 7.62 rifle and Shivaiyya carrying the .22. The forest in this area – around the Kadam River – is semi deciduous with teak, katha, mahua, ber, and some bamboo. The teak, katha and mahua shed their leaves in summer so the forest floor is carpeted with dry leaves, which makes for some noisy walking; not the best thing if you want to shoot any game. The ber and bamboo thickets retain their leaves, but are too thorny and thick to walk in. So, we stick to the pathways. The forest is interspersed with open glades carpeted with grass. These are the potential places to see something to shoot, especially small game.

As we walked, I spotted a large male peacock with a magnificent tail, sitting on a dead tree stump and yelling his guts out as they are wont to do. I exchanged my rifle with the .22 as shooting a peacock with a 7.62 would mean getting two stumps of legs as the residue. I crept up very slowly while Shivaiyya simply sat down on his haunches in the pathway and disappeared, waiting for me to complete my stalk. This is where the dry leaf fall comes to the aid of the quarry and is a bane in the life of the hunter. As I was almost in range, I stepped on a dead branch hiding under the leaves and it broke with the sound of a pistol shot. The peacock took off like a rocket into the air and was gone. I cursed my own clumsiness and stood up from my crouch only to see a small sounder of wild boar run across the clearing. Unfortunately, though they were in range, I had the wrong weapon in my hand; I simply stood by and watched them run. Some days are just not yours.

We proceeded on our way, this time with me carrying the heavier rifle until we came to a place where the path passed around the foot of a small and very rocky hillock. I wanted to tarry a bit and maybe climb it to look around, but Shivaiyya, very uncharacteristically, hurried me along. After we were well clear of the hillock, more than 2 kilometers away, he said to me, ‘Dora, you didn’t see it but there was a tigress on the hillock sitting before a cave. She has three cubs there and I saw the kill she brought for them last night. She was looking at us and I didn’t want to precipitate anything so I hurried you along.’ Much as I would have liked to see the tigress myself, I realized that effectively, he had saved our lives as well as the life of the tigress. Had I tried to climb that hill, she would have attacked and one of us would have died. Tragic, if it had been the tigress.

We stopped to rest on the bank of the Dotti Vaagu, a tributary of the Kadam, at a place where there was a good deal of shade. Below where we sat was a water hole in a bend in the river, always a very productive place to watch wildlife in the summer. Companionship is a wonderful thing and in my view the sign of a good companion is the quality of the silence when you are together. Shivaiyya was a very good companion. A man of few words except in the nights when he’d had his spiritual experience for the day. Then he would make up for all the silences of the day and would talk non-stop. But during the day we would walk and rest in silence, speaking only when it was necessary. This gave me a lot of time with my thoughts. We sat high up on the bank with our body outline broken by the bamboo clump behind us and dozed. I can’t describe the sense of peace and calmness that permeates you as you sit in a forest without any deadlines, phones, or email; simply being. Mobile phones and email didn’t even exist in those days and what are the deadlines for a schoolboy in his summer holiday? The heat or cold ceases to have any meaning after a while as your body gets accustomed to the outside atmosphere. Then sleep descends on you and you doze. This is not the sleep of those who are dead to the world. It is the sleep of those whose eyes may be shut but their ears are listening and their mind senses what is going on. You are still aware of what is going on around you even though you are apparently asleep. This ability is very useful because it enables you to rest in short breaks and keeps your energy high for the ongoing journey.

As I sit there, I can distinguish the regular sounds from those which are new and announce that we have company. This time it is a Chital hind, the scout who signals to her herd that all is clear. Not a very good scout if you ask me, because she didn’t see us. And had our intentions been less noble, she wouldn’t be signaling anyone else thereafter. As it was, I had no desire to shoot anything and was content to watch the Chital come to drink. There is perhaps nothing more cute and lovable than a Chital fawn. And there were several in this small herd. A good sign that the prey population was healthy, which meant that the predators would do well. A good prey population is a sign both that the predators have enough to eat and that they are therefore unlikely to stray into the villages to take the unwary goat or cow and thereby fall into conflict with their human neighbors from which there is only one exit – death for the animal. Whenever there is conflict between humans and animals, the animals always pay the price. That is what has gone very wrong with the whole issue of tiger conservation in India. It is habitat destruction which is the number one killer of tigers. It leads to human – tiger conflict and a lot of dead tigers. I believe we have reached a point of no return in this case and advise people to go and view as many tigers as they can while they are still there. I don’t think it will take all that long for us to reach a stage where to see a tiger you will need to go to an animal prison, aka, zoo, because none will be left alive in the wild. There is nothing more invigorating than a forest full of animals and nothing more dead and tragic than one which has been sanitized and is free from all animals. Our forests in India are fast reaching the latter situation. I am glad I was there to witness when this was not the case and hopefully I will not be there to witness forests devoid of their lawful inhabitants.

On another occasion, it was the height of summer with temperatures in the high 40’s and the deciduous teak forests almost totally bare. There was almost no shade and the forest floor was littered with dry leaves, which made an infernal crackling when we walked on them. Uncle Rama took me to see another part of the forest and he decided that we would walk. He would always wear leather slippers with the sole made of a car tire. They were specially made for him and he found them very comfortable. I personally wouldn’t wear them for love or money because they were so hard and unyielding that walking in them for a few hundred meters was enough to take the skin off the foot. He would wear a pair of army issue camouflage trousers and a shirt with large patch pockets in which he would have spare shells for his weapon. He would carry his shotgun, I would carry the .22 rifle and Shivaiyya or some other gun bearer would carry a heavier rifle, either a 9mm Mauser or a 7.62.

Neelgai (Blue bull male)

That day the trek was to be fairly long – walking at approximately 3 miles per hour, we walked a total of 8 hours that day – so Uncle Rama had asked Kishtaiah the cook to pack something to eat. As we left, I saw Shivaiyya carrying a tiffin carrier – three steel compartments in a metal frame, which made me very happy imagining what Kishtaiah would have packed into it. He was a fantastic cook, trained by Uncle Rama and his masala fried meat was simply superb. Strangely, nobody remembered to carry any water. We walked for about 4 hours, but didn’t see a single animal. It was our aim to shoot either a young Blue Bull (Nilgai), India’s largest antelope and one of only two species which exist in the Sahyadris, the other being the endangered Four-horned antelope, a small goat sized creature, very fast on its legs. Nilgai typically lie down in any shade they can find in the hot hours and so if you walk softly you can come up to one and get within range before the animal gets spooked.

The day got hotter and hotter as we walked. One principle of walking in the heat is not to keep drinking water as it only makes you thirstier, so none of us asked for water. The forest itself was very dry with no sign of any water anywhere. Eventually, we found a small bamboo thicket, which retains its green leaves throughout summer and provides shade. We were all very tired and hot and dusty. Not sweaty, because the sweat dried on you instantly due to the dry heat. Both Uncle Rama and I sank thankfully onto the ground in the dappled shade of the bamboo. Uncle Rama called for the tiffin carrier and Shivaiyya brought it to us. When we opened the cover, to our great surprise and considerable consternation, we found that Kishtaiah had filled all three compartments with a most delicious and rich dessert made of fried bread, khova (made from boiling milk until it almost becomes solid), ghee (clarified butter), and of course lots of sugar. We call it Dabal ka Meetha (bread is called Dabal-roti; which literally means double-roti) in Hyderabad. All three of us were very hungry and the dessert was delicious and so we ate it all up. After we ate, we realized that it was a mixed blessing indeed. I said surprise and consternation earlier because while the idea of eating just dessert may seem like having heaven on earth, one of the outcomes of eating a lot of sugar and fat is that you get intensely thirsty. And now we discovered that we had no water.

The forest was a uniform grey with the trunks of the teak trees standing tall in a desolate landscape. The breeze when it blew was straight from the furnace and started up little dust devils that swirled away into nothing. The stronger ones picked up a dry leaf or two, waltzing it up and then leaving it in midair, to float gently down among others of its tribe away from its earlier company. The cicadas ensured that everyone was aware of their presence. Cicadas make their distinctive sound using sound makers called ‘Tymbals’ on the sides of their abdomen. The sound is loud up to 120 decibels and the volume of thousands singing together in chorus can be imagined. This is what Wikipedia has to say about the Cicada. There are also recordings of the sound on this page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicada

Having finished our high energy lunch, we decided to head for home so that the walk would distract us from the thirst. Although the walk was as interesting as these walks always are, especially in anticipation of seeing some animal or the other as we went along, the thirst built up steadily, reinforced by the intense heat. In the summer in India it is only when the sun sets that the heat lessens, even to the extent that nights in summer in the forest can be cold. But in the day the heat increases especially in the afternoon when the sun is past its zenith. The fact that the forest was devoid of shade was not helpful either in alleviating the hardship. Eventually, almost after an hour of walking we came upon a Gond villager heading home in his bullock cart. He had with him his supply of water which he carried in a dried gourd, the mouth of which was plugged with some grass. Like all Indian villagers, he was more than happy to oblige us when we requested him for a mouthful of water. The water was tepid, smelt of the earth and grass but tasted sweeter than nectar. Taste is proportionate to need. Truly nothing quenches thirst like water. Now refreshed thanks to the man’s generosity, we walked on.

As we approached the village, I witnessed one of the strangest incidents of my life. We were almost in sight of the Gond village from where we would cross the Kadam River to get to Uncle Rama’s farmhouse. We could hear the sounds of the village getting ready for the night – dogs barking as the cattle returned to their pen, some cows bellowing their irritation at being hurried by the herd boys, others calling to their calves which tend to get lost in the melee. A lady calling her missing youngsters who had obviously gone off to something more interesting than the errands assigned to them. The ‘whap’ of a stick hitting the reluctant behind of an ox that refuses to do the bidding of its master. As we walked I said to Uncle Rama, ’It’s strange we didn’t see anything today after all that walking. Just two days ago, right here I saw an antelope watching me as I was returning home.’ I gestured over my left shoulder and pointed – and behold, an antelope was standing watching us go by. In less time than it takes to say this, Uncle Rama brought the .22 rifle up to his shoulder in one fluid movement and pulled the trigger. So, we did have something to show as a result of our very long and hard walk. I felt a little sorry for the antelope of course but it is strange how curiosity kills deer and antelope more than anything else. They will stand and watch instead of running away and so hunters eat.