“So, how did things get so bad?” I am sure you must have heard, asked or thought about this yourself. So have I. Many times, over the years whenever I saw a badly-behaved child being fed with the help of an iPad, a spaced-out teenager who seems lost in his electronic world where Facebook friends are more real to her than real human ones or when I read reports of rapes and murders being filmed on smart phones by stupid people. And my instant reaction is, “It was not like this 40 years ago. What went wrong?” And there would rest the case; until the next episode. This is 2019 and so when I say, ‘40 years’ we are talking about two generations; that is the 1980’s. It is not to say that everything was hunky-dory until 1980 and suddenly in 1981 it all collapsed. But it is a live demo of the truth of the ‘Boiled Frog Syndrome’.

For the uninitiated, this has nothing to do with cuisine, but with gradual social change which suddenly becomes starkly visible, having been unperceived for a long time before that. The parable is that if you put a frog into a pot of hot water, it will jump out. But if you put the frog into a pot of water at room temperature and allow it to get comfortable in it; then you light a fire under the pot and gradually heat the water, the frog doesn’t register that the water is getting hotter. It continues to feel comfortable in the water which is getting hotter and hotter until it reaches a point when it does register that things are not the same but by then it is too late, and the frog gets boiled. That is what happens to people and to societies. That is what I believe has happened to us in India.

Let me do a flashback to the time that I was growing up, which was in the 60’s and 70’s. We (me Muslim) lived in a multi-religious society, as we do now, but with a big difference. Nobody had TV’s or smart phones (we didn’t even have stupid phones), so our social life was with our friends. We played football and cricket; yes, really! I mean in the maidan (open field) near our house. We went to their homes and they came to ours. We participated in their festivals; not the religious ceremonies, but the fun and games, eats and sweets. And they did the same with ours. We knew them and their culture and religion, respected it, understood their boundaries and adhered to them, took an interest in their culture and they did the same with ours. We spoke about all this because there was no football or cricket to speak of and as far as I can recall, (cricket was a 5-day Test Match – a test of patience for everyone), politics was a given (Panditji was alive after all) and so there was hardly any discussion about that. We needed people and they needed us. So, we appreciated each other.

We lived in joint families, referred to our elders by our relationship with them or an honorific in keeping with their age. So, it was Dadaji, Amma, Baba, Mataji, Dadiji, Chachi, Chacha and so on. Hardly anyone was ‘Uncle’ or ‘Aunty’. There were some but not too many. It was the job of all elders to discipline us, teach us, tell us stories, guide us in our religious or cultural norms, customs and practices and when they were doing that, if any of our friends was around, they would get the benefit of this teaching, no matter which religion they came from. They listened with respect and so did we. Our culture was distinct from that of others, but I don’t remember anyone in my family ever referring to the culture of others in any even remotely derogatory term. I don’t believe that my family or elders were unique. They were ordinary people of the time. We learnt our cultural norms, manners, taboos, customs and practices from our environment and those around us and since we lived in joint families, there were plenty of those. It didn’t matter that Dad was away at work, Mom was always home and even if she went anywhere, one or both grandparents, an uncle or aunt or two were always around to ensure that we ate, slept, were safe, studied, went out and played and when it was time, prayed. Mom and Dad didn’t need to do these things exclusively.

We never ate out because it was considered uncultured to eat in a restaurant. People asked you, ‘Don’t you have a home?’ If you took a friend out to a restaurant it meant that he was not close to you or that you didn’t really respect him. Otherwise you would have brought him home. It was normal to eat at each other’s homes, no matter that in some cases the food laws are very different and rigid. But Brahmins, Marwaris, Kayasth and Reddy friends all ate regularly at our place. When those we knew to be particular about their food laws were coming, strictly vegetarian food would be cooked. Those that ate meat at our house did that because they wished to. Nobody forced of even suggested it to them. Once again, this was not unique. This was the norm. I recall dropping in at the home of my good friend from school, Gurcharan Singh. I said, “Sat Sri Akal” to his mother (Mummy), Dad (Dadji), Grandmother (Mataji) and “Hi” to his sister and brothers and him. They all said, “Come and eat”, as they were having lunch. His mother said, with a big smile on her face, “Aaloo paratha bana hai. Tujhe pasand hai na!” because she knew how much I loved it. As I sat down, Guru’s father pointed to a covered dish and said, “Usay utthay rakh do.” (Put that there; signing to the sideboard); meaning, take that dish away from the table. Guru jokingly said, “Dadji koi problem nahin hai. Yawar yahan kha lega.” His father was distinctly not amused. He said, “Khana hai tho kahin aur ja kar khaye. Ithey nahin.” (If he wants to eat, let him go and eat somewhere else. Not here.) What they were talking about was pork vindaloo. I would not have eaten it anyway, but for them it was not a joking matter. We respected each other’s traditions and unless someone volunteered to break his own tradition, it was not broken for him. Some Muslims went to their Hindu and Christian friends to drink alcohol, but nobody forced them to do it. If they chose to do it, that was their choice, just as it was the choice of vegetarian Hindus to eat meat in their Muslim friend’s homes, if they wished. Needless to say, many Hindus are not vegetarian and eat meat and fish.

Manners were a very big thing. You never addressed an elder by name. Or even as Mr. So-and-so. You either called him Uncle So-and-so or just Uncle. Same thing for the Aunties. If a boy whistled at a girl, anyone older around would simply thrash him right then and there. You asked permission, said ‘please’ and ‘thank you’. The role models you looked up to or who were mentioned to you were people who were known for their honesty, integrity, hard work, compassion; always for their values. What people owned was not the subject of discussion firstly because most people owned similar things, drove similar cars (if they drove a car at all) and lived in similar houses. The differences were not major and it was considered crass and highly uncivilized to mention money or the price of anything. If someone asked you how you were, you replied, “Very well Uncle/Aunty. Thank you.” You didn’t say, “I’m good”, because that is first of all, not the right answer because the person was not asking about your moral condition but your physical well-being and secondly because we thought it was their job to tell us if we were good or bad. Not ours to announce.

Money was in short supply though we never wanted for anything. We wore each other’s handed down clothes. We wore shoes until they became holey. Our clothes were hand-made to measure because that was the cheapest option. Readymade clothes were expensive and jeans you only saw in pictures. Pocket money was unheard of. You got money for the bus fare to school and that was it. Whatever else you needed had to have a reason behind it, and “I want it” was not a reason. We lived in bungalows on large plots of land because our parents had inherited them from their parents. We didn’t go on holidays and looked very enviously at those very few who went to Ooty for two weeks every summer so that they could return to Hyderabad’s heat and appreciate it better. But then, at that time you wore a sweater from November to February and the swimming pool (Public Swimming Pool in Fateh Maidan – does it even exist anymore – where Jeelani Pairak was the coach) only opened its doors in the middle of March because it was too cold to swim before that.

There were all of four career choices, medicine, engineering (mechanical or civil), Civil Service or Army. You picked one or if you didn’t, it was thrust upon you for all kinds of reasons out of your control and then you studied for the exams. When you got 80% you got presents and gave a party. If you got 90% people thought that you had cheated. Life was simple, uncomplicated and moved on at its own pace.

Then came the 80’s. TV came on the scene with its soaps, serials and news. The world suddenly opened. Education changed. Multiple disciplines became available to study leading to hitherto unheard-of career options. The Middle East opened up for jobs, so did America and Canada. Young people left to make their fortunes. In some cases, the wives and children remained behind. In most other cases, it was only the elderly parents who saw off their children at the airport to return to empty houses and loneliness. All in the name of money. Thanks to repatriation of funds and the effect of the TV, suddenly money was easy and material things, appliances, clothes, cars, motorcycles, all became affordable. Rapidly these became not only nice to have but grounds for competition with neighbors, friends and strangers. Suddenly we discovered that our neighbor’s name was Jones and we had to compete with them (Keeping up with the Joneses).

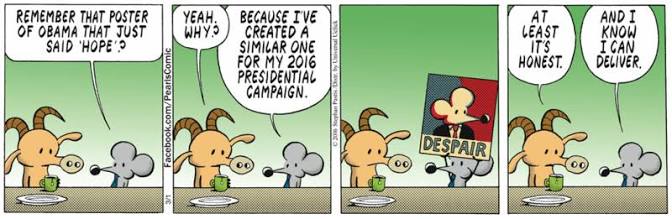

The 80’s sound like ancient history today in 2019 going on the magic number 2020. What do we have today? Hatred. We hate each other and that sells, that gets you elected, that gets you followers, it is chic, it is fashionable, and it works. It is most preferable to hate Muslims, but anyone else will also do, if there are no Muslims around. As long as you hate. That is the only thing that counts. So, our world has shrunk. We meet people like ourselves, who talk like we do, eat what we eat, like what we like and dislike what we dislike. We hate the same people and in each other’s rhetoric, we find solace. We live in our echo chamber and that has become our world. There are those among us who were born in this echo chamber. They don’t know anything else. But there are those who were born and lived in a world that was very different from this one. A world where there were no echo chambers, like there were no mobile phones, laptops, social media and even television. A world that was real. Today in our echo chamber, we sometimes ask ourselves this question, “What happened to that world?” Then we correct ourselves and ask, “What did we do to it?”

Comments (0)

Comments for this post are currently disabled.

Loading comments...