How to beat Goliath

Because size doesn’t matter

I have formulated 6 rules which I call David’s rules. These are for anyone facing the big one ...

The plantation years were not all about work and unions. They were a time of great fun and fulfillment; of wonderful friendships and personal growth. During these years I was able to be in the rain forests of the Western Ghats and see in their natural habitat, animals that it had always been my desire to see. I have always had an abiding interest in ecology with specific reference to mammals and their habitat. What better place to indulge that than the Indira Gandhi National Park inside which I lived for the 7 years that I lived in the Anamallais. My interest in ecology and wildlife was encouraged by my dear friends and mentors, Nawab Nazir Yar Jung and Capt. Nadir Tyabji. I was brought up on stories of encounters with animals in the Anamallais, which Nawab Saab used to tell us in graphic and wonderful detail. He was a born storyteller and listening to him, I could smell the forest and hear the sound of the cicadas and listen with close attention for the telltale crack of a twig which announces the approach of a big animal.

I have been truly fortunate to have friends who were much older and far more accomplished than myself. As a result, I learnt a lot from all of them. In fact, I used to make it a habit after meeting any of these people to take stock of what I learnt new that day. This focus on learning has been a lifelong habit of mine which I have consciously inculcated. The credit for that goes to my father, who one day when I had finished reading some trashy novel, asked me, “So what did you learn from that?” I thought about it and decided that it had been a total waste of time and since then started asking myself that question every so often. In those days we had no TV and soap and opera were two different words. So, the temptation to send the brain into suspended animation and sit with a vacant expression in front of the Electronic Income Reducer (my name for the TV) was not there. There was, however, more time for trashy friendships and wasting time in useless conversation. Asking myself what I had learned was an excellent tool to ensure that I did not waste time. Much later in life, I learnt and now teach the techniques of Effort – Impact Analysis and how to apply this to maximize the benefits of time. But all my life I have used this tool even when I did not know its fancy name.

Role models are a particularly important part of growing up. I was lucky that I had some of the best. It is a matter of pride for me that most of them, if not all, were the result of my own effort. In some cases, I was introduced to them by my father or someone else. But then I took it upon myself to be in touch with them and develop the relationship. I found that older people respond very positively to youngsters who are genuinely interested in learning. Consequently, I got a lot of face time with people who were twenty to thirty years my seniors. It is not that every one of these relationships was always positive and that I always gained something. Some people said things that were destructive, the memory of which remains with me to this day. What remains of the memory, though, is the way in which I took what was said to me as a challenge to disprove the statement. And Alhamdulillah, I always succeeded. It was not that these people were themselves, perfect. They were people and people are not perfect. But I taught myself never to criticize them either directly or indirectly but to learn from their behavior what to do and what not to do. That way the relationship remained intact and I continued to gain, no matter what they did or said.

The Anamallai Hills are home to the Lion-tailed Macaque (called Yal-Tee-Yam – LTM), an endangered species of primate that is found only in these forests. The Anamallais are famous for the elephants that they are named after (Tamil: Anai – elephant, Malai – Hills). Ever since my arrival in the Anamallais I was most keen to see wild elephants. And I got my chance just 5 days after I reported at Sheikalmudi Estate. This first sighting was almost the last sighting, not just of elephants but of anything at all. Let me tell you the story in sequence.

I was brand new on the plantations and had just got a new Jawa motorcycle, which I was delighted about. It was late afternoon when the phone rang in the Sheikalmudi Estate office and it was Mr. Raza Husain on the line. Raza bhai was the manager of Lower Sheikalmudi Estate of which one day I would become the manager. LSM borders the reserve forest, a part of the wildlife sanctuary and national park that the Anamallais is located in. “Do you want to see elephants?” he asked me. That was like asking someone, “Do you want a million dollars?” Of course, I wanted to see elephants. I had been dreaming about seeing elephants. And imagine a chance to see them just 5 days after arriving in the Anamallais. I leapt on my Jawa and off I went to Raza bhai’s estate. Raza bhai asked me to meet him in the Candura Division where he was waiting for me.

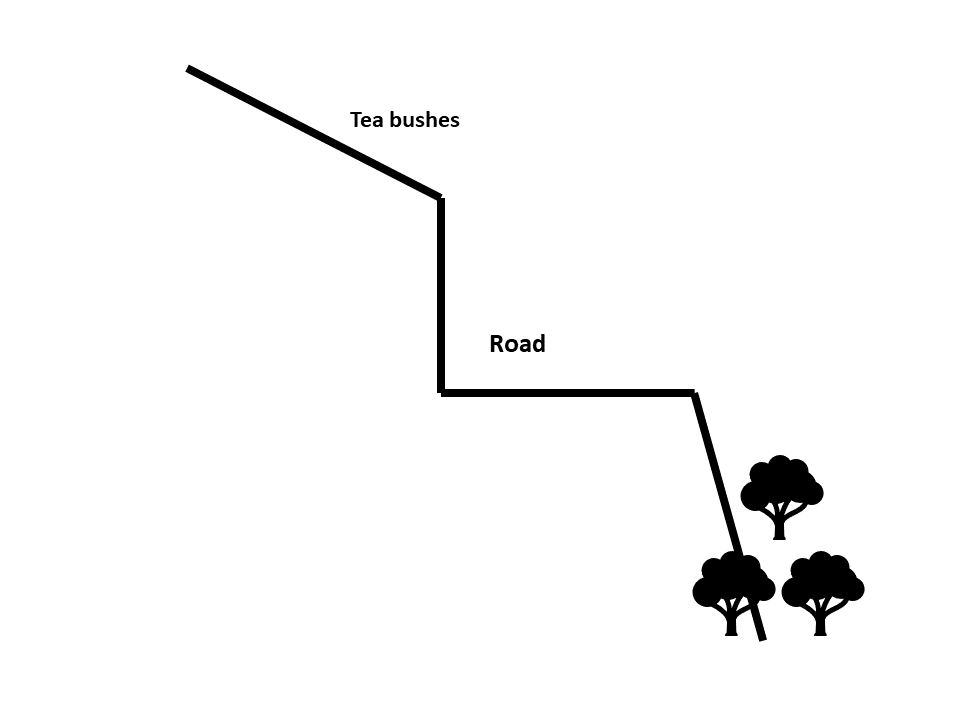

Candura is a tea division that is surrounded by jungle. One of the roads leading to it passes through a thick patch of forest in which I had some close encounters with bison (Gaur) years later. But that is another story. The tea in Candura is planted on the contour and it is a very beautiful sight. In the middle of Candura are the Labor Lines where the Candura workers live. These quarters each had a small vegetable garden with some banana plants. Elephants love bananas. So periodically they would raid the gardens. The owners would raise a hue and cry and beat drums or let off firecrackers to drive the elephants away. The elephants would then retreat in a foul mood into a small, heavily wooded canyon that was adjacent to the quarters. This was the usual sequence of events and this is what had happened on that fateful day just before my arrival on the scene.

When I arrived Raza bhai met me on the road just below the Labor Lines. His little son Mustafa was with him sitting on the petrol tank of his bike. It was past 5.00 pm and the sun sets very quickly in this part of the world. Mustafa was getting nervous at the idea of going to see elephants so Raza bhai said to me, “I will give you a guide and you can go see the elephants. I will wait for you to return here. It will get dark very soon and then you won’t be able to see anything so hurry.” I readily agreed. Anything to realize my lifelong dream to see elephants in the wild. Raza bhai called a man by the name of Karpusamy who was to be my guide. Karpusamy spoke only Tamil. At that time, the only Tamil word I knew was ‘Tamil’. So even though Karpusamy was to guide me, what emerged was a lot of inspired gestures and guessing. It was later that I learnt to speak Tamil fluently, in three months.

As it was getting dark, we were in a hurry and with Karpusamy in the lead, we set off along the road, which circled the ravine, looking down into the ravine with great concentration since that is where the elephants were supposed to be. Once in a while we would hear the sound of some breaking branches, so we knew that the herd was still there. I cannot describe for you my own excitement. I could hardly breathe. We left my motorcycle by the side of the road and I had the presence of mind to push it into the tea between some bushes in one of the plucking lanes in case the elephants decided to take this road back into the forest. I did not want them to give their attention to my motorcycle. Neither me nor the bike would survive that. As it turned out, that was a very wise decision.

I was very anxious to get to where the elephants were so that I could get my first glimpse of an Asian Elephant in the wild. This had been a lifelong dream of mine and I was in the right place for it – a place named after them – Anamallai – Hills of the Elephants. The topography of where we were walking was that we had tea on one side and the ravine on the other. The road itself had a sharp, almost vertical embankment about six to seven feet high above which was close planted tea.

It is at times like this, often faced with the prospect of great danger that we live most intensely. That is why people seek thrills; the adrenaline gives them a high and they need a fix again and again. I was aware of every sight, sound, and smell as I walked. This is a safety measure also apart from enhancing the pleasure of the experience because in such a situation where you are likely to meet an animal which is potentially dangerous, you’d better have all your wits about you.

As we walked along looking down into the ravine hoping to get a glimpse of the elephant herd, we could hear them moving about occasionally, breaking a branch, or shaking a tree to drop its fruit. As we neared a bend on the road, the cicadas fell silent and all sounds from the ravine stopped. The forest became completely silent as if waiting for something to happen. And then something happened. I suddenly heard an explosive sound like a tyre burst. This is the warning sound that an elephant makes just before he is ready to launch a charge. I looked up in shocked surprise and what did I see? Not more than fifty to seventy meters ahead of us, bang in the middle of the road was the herd bull. He had come up on the road when he probably realized that we were coming close to his family. And his intentions were not honorable at all. It takes longer to narrate this incident than what happened that day.

It seemed like a split second and in any case could not have been more than a second or two. The elephant made the alarm warning sound. Karpusamy and I looked up simultaneously, shocked out of our wits to see this huge bull elephant standing so close ahead. Karpusamy screamed, “Dorai!!” and spun around and ran back towards me. The elephant trumpeted and charged. You must hear the trumpet of an angry elephant to know what fear is. It is a scream. It is a loud scream. The volume of sound is all that can be expected from that great body. And it turns the knees to jelly instantly. A charging elephant moves at 50 miles per hour. With a stride of 12 feet at a go, it did not take long for that elephant to cover the distance from where he was to where we were.

As for myself, the next thing I remember is that I was sitting under some tea bushes up on top of the vertical embankment. There was no sign of Karpusamy. I do not remember running or jumping or anything else. Just that I was out of reach of the elephant and very frightened but safe. The elephant was enraged that he did not get me and vented his anger on the embankment below where I was sitting. He dug up the embankment with his tusks and threw up mud all over the place. His angry trumpeting brought the cows out of the ravine. The cows calmed him down and eventually the whole family moved away towards the forest.

I simply sat there, frozen with fright in the gathering dark as the cold forest night closed in, wondering how on earth I had managed to get up on the embankment without touching a thing. I know I cannot leap seven feet high. The wall was vertical. And yet there I was sitting safely out of reach of the elephant. This is a mystery that I have tried to solve many times to no avail. Many times, after that evening I went to the site of this incident and actually measured the wall. It was seven feet tall. I looked to see if there were any handholds or footholds that I could have made use of. There were none. Yet there I was on top. Maybe it is true that fear lends wings to the feet. As it is true that when your time has not come, you cannot die. And die, I would have, very quickly and thoroughly, if that elephant had caught me that evening. For a couple of days after that, I used to wake up in the night in a cold sweat with the angry trumpet of the elephant ringing in my ears. Mercifully, that memory has worn off, but the memory of the entire incident is still vivid in my mind.

And what about Karpusamy, you ask. Well, he did the only thing that he could have done. He took a flying leap into the depths of the ravine. He just ran and leapt off the edge into the abyss. It must have been about fifty feet to the bottom, but like in my case, it was not his time. So, he landed on the top of a tree. Bruised, but not hurt gravely at all. Once all the excitement had died down, he climbed down to the bottom and walked back to the Labor Lines. That is what I also did once I got my senses together and ensured that the elephants had indeed left the place. It had gotten quite dark by then and I did not have a torch with me. But once I climbed down from the embankment, I was on the road and all that was necessary was to keep walking on the circular road till I got to the Labor Line. The biggest challenge was to keep walking in the dark even though I was seeing elephants in every shadow. My childhood training in the forests of Adilabad came very handy. I could recognize sights and smells and knew at least cognitively that there was no real danger anymore. Controlling my heartbeat was another matter.

Our friends waiting for us at the Labor Lines had an exciting time of it as well. They could not see what was happening as there were a lot of trees between them and us. But they heard the angry trumpeting of the elephant and all the commotion he made. Then they saw the herd move out. But they did not see either Karpusamy or me and so they came to the only conclusion that anyone would have – that I had just ended the shortest career in tea planting that anyone had ever had. Since both of us did not get back to them for a couple of hours, by the time we arrived, there was much sadness and apprehension. So, the welcome that I received was the biggest that I have ever had. I was hugged and kissed and made much of. And people wanted to hear the story in total detail of how I escaped the elephant. My stock went up very high also, because being India and the plantations, my escape was seen by some as a sign of my high spiritual status where I had actually performed a miracle to save my skin and some ‘thing’ had transported me out of reach of the elephant. As for myself, thing, or no thing, I was jolly glad I’d seen wild elephants and lived to tell the tale.

The biggest learning for me in this entire incident was the difference between theory and practice. I knew from all my reading and talking to experts that even if you get to the stage where you are facing an elephant which snorts in warning, all you need to do is to start moving back slowly. Not run. Not make any noise. Just move back slowly. Continue to face the animal but keep moving away and increase the ‘trigger distance,’ which can precipitate the charge. Now, does this work in practice? Who knows? What I did and what you will also probably do if you are ever in such a situation, is to turn around and run like hell. Knowing fully well that a human being has as much chance of outrunning a charging elephant as they have of outrunning an express train. And that unlike an express train, this one is not bound by the railway track. The theory is good. But practical life sometimes plays tricks with theory.

Another big learning was the need to take risk if you want to make your dreams come true. Certainly, there is the importance of preparation and contingency planning, but in the end, there must be that leap of faith. With this comes the excitement of the win. It is the absence of guarantees that makes the win so thrilling. If there are guarantees, if safety is taken to a level where risk is eliminated completely, then there is no thrill of winning. This does not mean that we disregard safety or take unsecured risks. It just means that there comes a time when you need to act. At that time, you may be working with incomplete data, with incomplete resources, with incomplete plans. But you need to act. And then as you move forward you will find that what you need comes to you from sources you could not imagine.

Barbara Winters says: “When you come to the end of the light of all that you know and are about to step off into the darkness of the unknown, faith is knowing that one of two things will happen; there will be something firm to stand on or you will be taught how to fly.”

I was taught how to fly.

Please log in to leave a comment

Loading comments...

I have formulated 6 rules which I call David’s rules. These are for anyone facing the big one ...

One of my friends who comes from ...

I have said this a million times, if I have said it once – the three crimes committed on society with society’s blessing are: Commerci...